He’s this kind of shadow coming back from ages that most of the 20-years old people have even never heard about… We’ve met the last king of the U95kg category in his homeland of Poland. The interview was almost a week long, which was the appropriate time needed to try to talk about such a rich journey. It’s an old but nowadays fighter story, universal and singular, a daily struggle started from the ground and keep heading up to the sky. – JudoAKDReplay#001.

[FRA – Cet article est une reprise de la version anglaise d’un portrait publié en juillet 2017 dans le bimestriel français L’Esprit du judo. Cette version anglaise a été mise en ligne en août 2017 dans l’ancienne version du site Internet de L’Esprit du judo et reprise par le site JudoInside, mais n’était plus visible depuis la mise à jour dudit site à l’automne 2020. Le voici à nouveau.

ENG – This article is a reprint of the English version of a portrait published in the French bimonthly L’Esprit du judo in July 2017. This English version was put online in August 2017 on the old version of the EDJ website and taken over by the JudoInside website, but no longer appeared since the redesign of the said site in Autumn 2020. On this June 26, as Pawel Nastula blows out his 54th candle, here it is again.]

Enter the Dragon

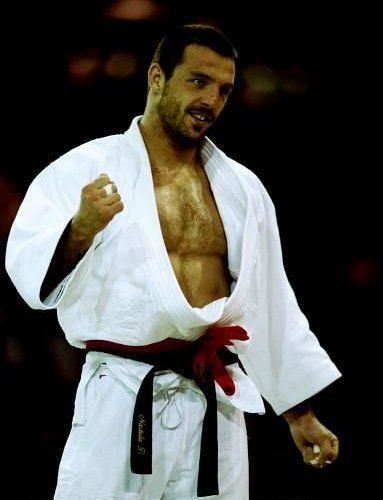

Aged 47, Pawel Nastula’s 1.86 meters thousand detailed tall body reveals the intensity of last three decades. His broken nose contributes to a loud voice; his X style knees testify of thousand of arthroscopies; his stiff back and neck only turn on slowmotion… “I was an agitated kid. I saw judo by a window and, as a child from Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon traumatized generation, I wanted to try this ‘japanese sport’. Unfortunately you had to be 10 years old and I was only 9. It was times of Cold war and martial law in Poland, so rules were rules. I cried from it but came back one year later. With retrospect, I understood that 10 was the perfect age for starting judo. I didn’t have time to get bored. Neither before, nor after.”

From a Glorious Legacy

“High level sport is different than other activities because there is only two ways: you are either on top, or you are nobody.” Despite the unevitable ego wars of any such human journey, Pawel Nastula enters a stable and well structured Polish national judo team in the late eighties. Helped in the beginning by Japanese Hiromi Tomita, Waldemar Sikorski is headcoach from 1968 to 1980, when pioneers like Antoni Zajkowski and Marian Talaj both become bronze medallists in Munich ’72 then Montreal ’76. Ryszard Zieniawa is then in charge until 1991 and leads Poland to the second place behind Japan at the 1986’ Kano’s Cup. The golden generation of Waldemar Legien and Janusz Pawlowski -the second one was bronze medallist in Moscow ’80 then in Seoul ’88, meanwhile the first one was Olympic champion of the U78kg category in 1988 then Olympic champion of the U86kg category in 1992- slowly leaves the place to let enter Rafal Kubacki, Beata Maksimow and Aneta Szczepanska, who happened to become the only Polish female Olympic medallist back to 1996 in Atlanta.

After the beginning of a competition with “Waldek” Legien, Pawel Nastula moves to the U95kg category. He is only 21 when he becomes the astonished silver medallist of the 1991’ World Championships. He’s defeated in final by the French Stephane Traineau –who will turn to be, through almost a decade, his toughest opponent ever. The young and vigorous Wojciech Borowiak’ student at the Warsaw AWF Club gives that day a first warning to the future. His trademark? Very few international competitions, due to a tight home agenda. “At that age, we had to be part of at least four national competitions a year. This system really helped us to keep up the pace. The level was high. Today things are different. National champions go directly to Grand Prix or Grand Slam, but being early on that level makes them lose their confidence quickly. Being a Polish champion during those years? It meant being tough at international level”, says the man who ended with twelve national individual titles.

Golden Age of Grace

His wedding with the affectionate Joanna, soon mother of Marta and Monika, their two beloved daughters, gave to the former famous Warsaw and Wroclaw’s nights entertainer the balance he just needed. Step by step, his promised talent becomes reality. His 5th place at Barcelona’s ’92 Olympics, then his early loss at the Hamilton’s ’93 World Championships due to a lack of endurance and a too short rest after a crossed ligaments surgery upsets him. Those two “bad” performances put him far from a much needed financial security. Then coached by a Borowiak-Rzepkiewicz ticket –two key coaches with Antoni Zajkowski for his career, during which relationships with his Federation were not so easy-, he announces for Gdansk European Championships in 1994: “If I lose, I quit.” And he wins, and not only those Europeans. He strikes four years in a row and remains unbeaten during three European and two World Championships, but also two Paris tournaments and at the ’96 Olympic Games in Atlanta. “More than that invincibility series, I remember my state of mind at that time. I felt relax, positive. I took the fights one after another, without any pressure except the will to fight well. And on top of that, I enjoyed it.” His best souvenir? Atlanta, of course. His Nemesis Stephane Traineau loses early in the other side of the draw. “He was greatly relieved” smiles, twenty-one years after, the eventually two consecutive French Olympic bronze medallist, remembering the way the Polish looked at him on the warming-up area. Still, “it was the hardest draw I could imagine” says the so-called “Nastek” by his teammates. He defeats opponents such as Luigi Guido from Italy, Pedro Soares from Portugal or Aurelio Miguel from Brazil. Their length and grip are an issue to solve for the moving guy Nastek is. But the Chiba’s ’95 World Champion gives an astonishing ne waza lesson during the first round against Antal Kovacs from Hungary, the reigning Barcelona’s Olympic champion himself. This demonstration shows all his coming opponents that putting a knee on the ground in front of him on this upfront July 21st, 1996 is not a good idea. Adding his left and right skills on seoi nage or ko-uchi-gake, this Olympic title –the third and the last till now for a Polish judoka- could not end in any other hands than Pawel’s.

Ground Hero

The way he destroyed –in one single spread(!)- the reigning Olympic champion in this highly awaited first round of the ’96 Olympics remains unforgettable. Collar-pelvis clamping, osae-komi attempts and academic juji-gatame’s ending… However, this ne waza demonstration was just a kind of haïku compare to what he already showed during 2 minutes and 53 seconds against Sergueev from Russia in the ’95 Birmingham European Championships final. “I’ve lost some fights on ne waza at the beginning of my career. I remember the ones at a Juniors European Championships and in final of the ‘91 Seniors World Championships. So I’ve decided to work on this and it paid. Little by little, the ground sessions became a matter of sensation and rhythm. I’ve realised that by working like this I was less tired… but I exhausted my opponents. I saw in their eyes that they became afraid to go to the ground with me. It made their fighting scheme fragile, even on tachi waza…”

1998, the Beginning of the End

What goes up comes down. One year after his Olympic triumph, Pawel Nastula wins his second World title in a row in Paris ’97. With Jeon Ki-young from South Korea in U86kg, Marie-Claire Restoux for France in U52kg and her teammate David Douillet in O95kg, the Polish is one of the four to have completed this hat-trick in three years. He doesn’t know it yet but it’s already his swan song. During the Autumn of 1997, the U95kg turns to become the U100kg. A deadly change for Pawel Nastula, who weighs only 97 kg. Moreover, a boomerang effect for four full-on seasons in a row backfires at him. “After Paris, I should have taken a long break. My body, my soul, everything was saturation. Of course I won in Bercy, but I was already beyond the limit. It was partly my fault: when you win everything, you always want to fight. I knew that there wouldn’t be World Championships in 1998 so after Atlanta ‘96, I’ve decided to fight in Paris ‘97 and see later for the future. And I saw, indeed… Having a coach by my side would probably have helped me during those years. Actually, I fought too much to have a say on that and wasn’t clear-headed enough…” It’s in Warsaw, in his hometown, that he takes two of the three blasts of his decline. On March 15, 1998, Stephane Traineau beats him in final of the World Cup -his first important loss since Hamliton’s World Championships, four and a half years before. Beaten twice in two matches two months later at Oviedo’s European Championships, he’s defeated again in Warsaw’s final in 1999, this time by Martin Padar from Estonia. A couple of weeks later, Stephane Traineau (again!) beats him by osae komi in the Bratislava’s European Championships final, the last honourable rank of his career. His judoka’s agony, surrounded by a lot of injuries and by some not-so-easy relationships with some of his teammates, will continue almost five years until 2004, when he misses from a waza-ari his fourth Olympics ticket.

The MMA Years

After those sad final years, the career of the grey haired U100kg finally finds a second breath. “I was popular in Japan, where the Pride was burgeoning. They contacted me. I still had things to say so I went for it.” His first matches were against three of the World Top 6 –amongst which Aleksander Emelianenko, brother of legendary Fedor. So the first contact was somehow punchy. Winner of five out of the eleven bouts he fought between 2005 and 2014, the newbie is far from being ridiculous. But his last fight against a fellow citizen, the culturist Mariusz “Pudzilla” Pudzianowski, 145 kg, looks like the match he should have avoided altogether. “I switched on a light between judo and MMA and people respect me for that” he remembers, in spite of “a doping misunderstanding” at the end of 2006 – “my explanations about it were accepted” he precises. “I went to MMA at the end of my judo career, he adds. Neither at the beginning, nor in the middle, like many others do. I had some references, a status and, even if my old age was clearly a problem to reach the summits of MMA, I think I’ve proven what judokas were capable of in that sport where they are not supposed to be the most at ease.” He trained in California at Dan Henderson’s, in Croatia with Mirko Pro Cop, his wife and daughters spent three weeks with him in Japan… “Today, I pay the price of all that. I always kept in mind the world of judo, even during the years I had to go away from it. Despite that, I can feel that the judo world remains a bit cold with me. I did sacrifice a bit of my judo ‘purity’ but I have no regrets about it because I know that I acted like a man, like a father and for my family. You can be punched in MMA and it’s painful, but you can also be punched in life and it’s painful too, no? Being a judo champion doesn’t pay the bills. I was young when I lost my father so my priority as a husband and as a father was to secure my wife and daughters’ future. Now that it’s done, I think I can be of use for judo. The question is: does judo still want me?”

A Future Like a NeverEnding Past

Guest of some seminars in Poland and overseas, Pawel Nastula owns two big places in Warsaw where 2,000 members come daily for judo, fitness, crossfit or MMA. Now that his family is economically safe, the old champion sincerely wants to give back to the Polish judo a bit of what he received during his early years. In February 2016, he takes a first step with two old fellows from his judo years. The first is Artur Kejza, from Rybnik, coach of the promising Piotr Kuczera, bronze in 2016 at the European Championships after some impressive wins over Ilias Iliadis from Greece or Aleksandar Kukolj from Serbia. The second is Artur Klys, Cracow’s resident husband and coach of Katarzyna Klys, World and European medallist, who tries to qualify for her third and last Olympic Games at the age of 30. “Both were the first in the judo world to reach out to me when I said that I was ready to help” insists the “never invited guest in Bercy” since his World title back to 1997. His only federal apparitions, despite an almost complete aura, were for some youth competitions’ ceremonies… In July 2016, the Spanish international training camp of Castelldefels was a quick comeback to judo world. Many of his former opponents, now coaching other national teams, didn’t even recognize him at first. End of September, he made his first appearance on a chair, coaching Katarzyna Klys at Zagreb Grand Prix. Then, a crescendo leads up to what should become the Day One of the new era of Polish judo: the European senior Championships, which took place in Warsaw from April 20th to 23rd, 2017. Unfortunately for him, things turned differently. With two individual 5th places –among them Katarzyna Klys [cf. EDJ#68]- and a Silver medal in the women team competition, this was not exactly the new era in the sense that Pawel and the two Artur expected it. On April 27th, the new federal organisation came out with none of the three in it, in spite of “promises made” to Pawel during the federal elections a couple of months before. Less angry than deeply humanly disappointed, Pawel waved goodbye with a single Facebook post, which was shared 285 times and liked by 1,400 people. In his message, the last king of the U95kg takes his distances with what he names “the immobilism and nepotism smell of the circles of power”, explaining his willingness to go far from it all from now on and only remain involved with children classes and daily educative judo. A message like a wake-up call: the last Olympic champion of Polish judo is hurt by the beloved sport which made him become the man he is. But he’s not ready to watch it fall speechless yet. – Written and translated by Anthony Diao. Overview by C.T.

A diary of this week in Zakopane can also be read here (in French).

More Replays in English:

- JudoAKDReplay#002 – Gévrise Emane – Turn Lead into Bronze (2020)

- JudoAKDReplay#003 – Lukas Krpalek – The Best Years of a Life (2019)

- JudoAKDReplay#004 – How Did Ezio Become Gamba? (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#005 – What’s up… Dimitri Dragin? (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#006 – Travis Stevens – « People forget about medals, only fighters remain » (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#007 – Sit and Talk with Tina Trstenjak and Clarisse Agbégnénou (2017)

More articles in English:

- JudoAKD#001 – Loïc Pietri – Pardon His French

- JudoAKD#002 – Emmanuelle Payet – This Island Within Herself

- JudoAKD#003 – Laure-Cathy Valente – Lyon, Third Generation

- JudoAKD#004 – Back to Celje

- JudoAKD#005 – Kevin Cao – Where Silences Have the Floor

- JudoAKD#006 – Frédéric Lecanu – Voice on Way

- JudoAKD#008 – Annett Böhm – Life is Lives

- JudoAKD#009 – Abderahmane Diao – Infinity of Destinies

- JudoAKD#010 – Paco Lozano – Eye of the Fighters

- JudoAKD#011 – Hans Van Essen – Mister JudoInside

- JudoAKD#021 – Benjamin Axus – Still Standing

- JudoAKD#022 – Romain Valadier-Picard – The Fire Next Time

- JudoAKD#023 – Andreea Chitu – She Remembers

- JudoAKD#024 – Malin Wilson – Come. See. Conquer.

- JudoAKD#025 – Antoine Valois-Fortier – The Constant Gardener

- JudoAKD#026 – Amandine Buchard – Status and Liberty

- JudoAKD#027 – Norbert Littkopf (1944-2024), by Annett Boehm

- JudoAKD#028 – Raffaele Toniolo – Bardonecchia, with Family

- JudoAKD#029 – Riner, Krpalek, Tasoev – More than Three Men

- JudoAKD#030 – Christa Deguchi and Kyle Reyes – A Thin Red and White Line

- JudoAKD#031 – Jimmy Pedro – United State of Mind

- JudoAKD#032 – Christophe Massina – Twenty Years Later

- JudoAKD#033 – Teddy Riner/Valentin Houinato – Two Dojos, Two Moods

- JudoAKD#034 – Anne-Fatoumata M’Baïro – Of Time and a Lifetime

- JudoAKD#035 – Nigel Donohue – « Your Time is Your Greatest Asset »

- JudoAKD#036 – Ahcène Goudjil – In the Beginning was Teaching

- JudoAKD#037 – Toma Nikiforov – The Kalashnikiforov Years

JudoAKD – Instagram – X (Twitter).