A few months after our interview published in spring 2025 (« Your time is your greatest asset », JudoAKD#035), Nigel Donohue, British Judo’s performance director from 2013 to 2025, publishes on LinkedIn a training model that sparks many reactions, to the point of being reproduced in full by the Spanish website JudoTraining. A look back at a process developed over fifteen years and directly inspired by the pedagogy of Patrick Roux, Hiroshi Katanishi and Go Tsunoda. – JudoAKD#045.

A French version of this interview is available here.

What types of judoka are most concerned by the Hajime-Matte model?

The Hajime-Matte model is a versatile framework designed to benefit all judokas, regardless of their level of experience. From a pedagogical standpoint, the model is particularly effective for beginners, as it allows coaches to do two things. First, it allows them to simplify technical development, since it facilitates the breakdown of technical development by amplifying the key elements of the model, thus providing a clear focus for training and understanding. Then it allows them to create a shared language, in the sense that it establishes a cimmon vocabulary promoting collaborative learning – an essential aspect when the judoka alternates between the roles of Tori and Uke.

What about more experienced judoka?

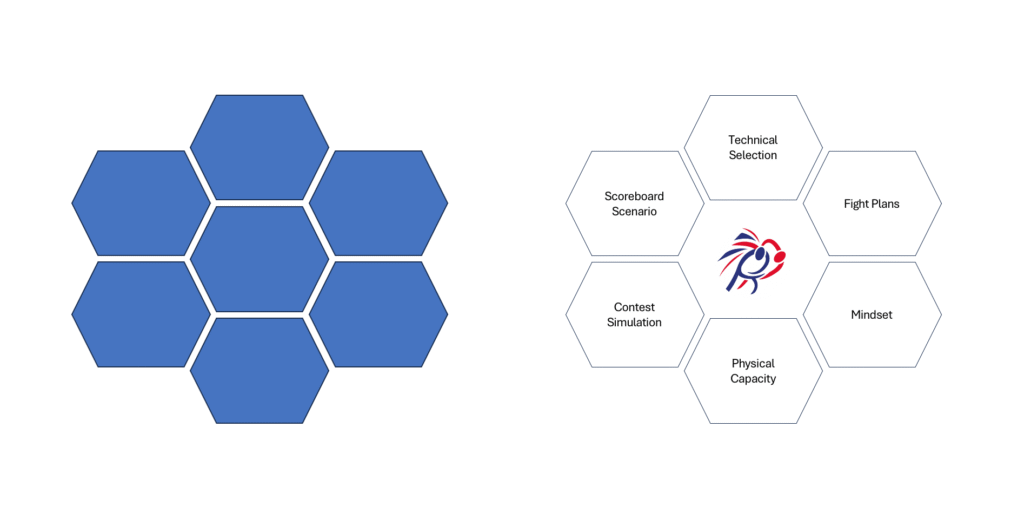

For elite judoka, the model becomes a more sophisticated analysis tool. It allows them both to prioritize and to strengthen their « super strengths. » By prioritize, I mean the fact of allowing them to easily analyze their performances in order to identify their technical strengths and weaknesses according to the different phases of combat, which allows them to guide their technical and tactical development. By strengthen their « super strengths, » I mean the fact of allowing them to reinforce and optimize their major technical assets – their trademarks – in order to maximize their effectiveness at the highest level. This can be assessed and confirmed through systems like Emidio Centracchio‘s, JudoData (www.judodata.com), which shows that elite judoka possess technical super strengths compared to lower-level athletes.

What training model did you learn or build during your early years?

When I retired from competition in 1998 to become a national coach in Scotland, I lacked knowledge about formal technical or pedagogical models. My beginnings as a coach were mainly guided by the experience accumulated during my career as an elite judoka and Olympic wrestler – I was coaching somewhat like a retired athlete. This initial approach was strongly influenced by the respected coaches who marked my career: Alan Jones, Tony MacConnell, Seth Birch, Neil Adams and Mark Earle.

How did they influence you?

They passed on to me a professional work ethic and a quest for technical perfection in three key areas: kumikata (gripping), nage-waza (throwing), and transition (the link between standing work and groundwork). Those years also gave me an Eastern European perspective on technical judo and intensive training. I had – and still have – a very structured and professional approach to the role of national coach, which served as the foundation for my training process. In hindsight, my early years were real on-the-job learning: I was learning, making mistakes and continuously correcting. My goal then became to connect my decades of experience in two Olympic sports to build a coherent coaching system. This constant effort to formalize my practice laid, without me realizing it, the foundations of the Hajime-Matte model.

You mention Patrick Roux, Hiroshi Katanishi and Go Tsunoda. What aspects of their pedagogy led you to evolve your understanding?

The arrival of Patrick Roux as UK national coach around 2009 – a period when I was England’s national coach and part-time performance analyst – marked a major turning point. I’d already met Patrick around 2001, during a training camp organized for the British police, and I’d come away very much enthused. But the technical knowledge and expertise shared by Patrick, Go Tsunoda and Hiroshi Katanishi were nohing short of mind-blowing during heir time in the UK between 2009 and 2012.

What do you mean?

What I mean is that at that point, I had spent several years developing my own foundational system, but their level of expertise literally « messed me up » – in a good way. I went through a period of creative confusion, that classic realization that « the more you know, the less you know »… I struggled to integrate their very advanced technical and tactical expertise into my existing training process. It was a revelation: I needed a more solid and adaptable framework to exploit and organize such rich knowledge… Having had the chance to work alongside Patrick, Go and Katanishi was a privilege and a defining experience that still influences my coaching approach today.

You also mention your friend Michael Bourne. How was he also a source of inspiration for you?

Michael Bourne is now performance director at the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA). He’s an exceptional expert in skill acquisition and performance analysis. Working under his direction as a performance analyst for judo – alongside my role as England’s national coach – gave me an incredible learning environment. I had daily access to his analytical rigor while simultaneously benefiting from the technical expertise of Patrick, Go and Katanishi… This period was initially disorienting: I temporarily lost the structure of my personal coaching process while trying to connect all these learning sources. But since Michael and I both have a strong taste for structuring and models, our exchanges were essential. He helped me understand that creating a model was the key to connecting the technical depth of the Japanese and French experts with an analytical, performance-driven approach.

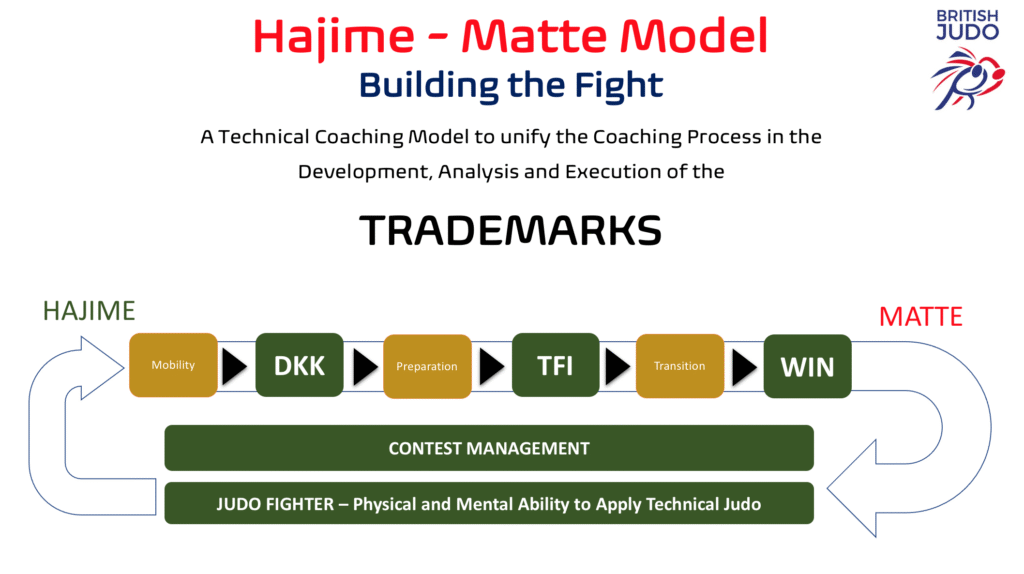

Over a few years, this systematic effort to connect all this learning to competitive judo inspired the birth of the Hajime-Matte model. Today, this model has become my reference training process. It’s a powerful tool that allows me to connect any technical program, training plan or performance analysis to this framework. It appears simple, but is devastatingly effective.

What are the essential points of this model?

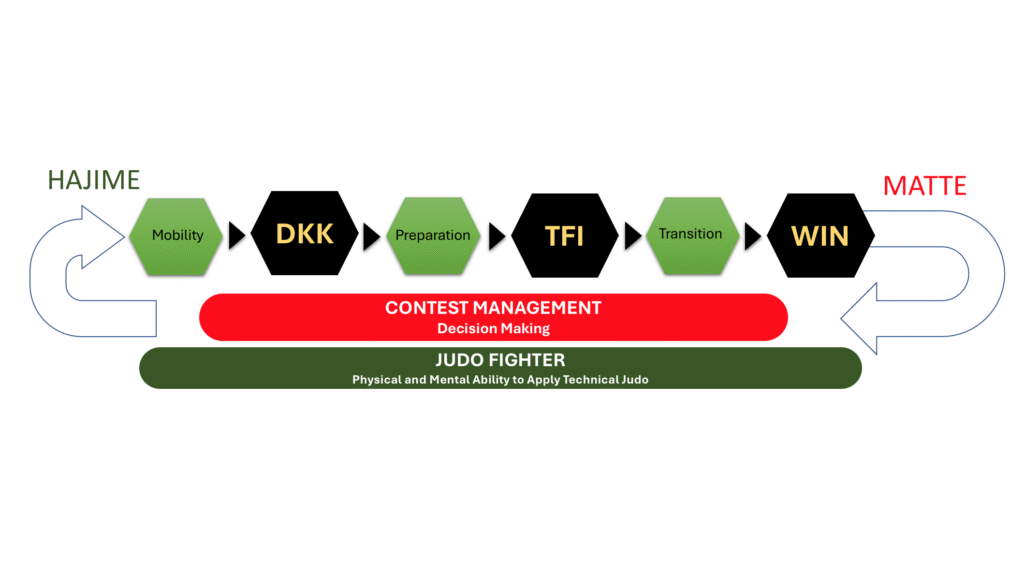

The Hajime-Matte model is a principle-based framework that reflects the linear flow of a judo match, from hajime (start) to matte (stop). It’s structured around six key phases, dividing the match:

– DKK (Dominate Kumi-Kata): this is the first super strength, centered on dominating the gripping battle to control the bout;

– TFI (Throw For Ippon): this is the second super strength. It’s focused on a repertoire of mastered throws, including a key technique capable of being executed under pressure;

– WIN (Win In Ne-waza): this is the third super strength. It focuses on mastering groundwork, notably including a « signature » technique of direct transition from standing position.

These three super strengths are connected by three linking phases, true « foundations » of the model:

– mobility: dynamic movement, posture and distance management;

– preparation: action-reaction and off-balancing tactics;

– transition: fluid and controlled connection between standing work and groundwork.

The entire model is underpinned by Contest Management – Decision Making. This is the central pillar: the athlete’s physical and mental capacity to execute a tactical plan, to adapt their strategy to each phase of the match and to make the right decisions under pressure to win.

Speaking of decision-making, there’s a lot of interesting literature on this subject from football, rugby or basketball. Do you think judo should open itself more to research and knowledge from other disciplines?

Absolutely. The « contest management – decision-making » skill is an essential skill in high-level sport, and I’ve fully grasped its value throughout my coaching journey. As an athlete, I didn’t really understand the tactical management of a match; my strategy often came down to « attack again » or « defend by attacking ». This cost me major matches when I was in a winning position. Observing competitors like Marco Spittka or Mark Huizinga during my time at TSV Abensberg opened my eyes to the importance of tactical skills I’d never been taught. So I’m convinced we need to draw inspiration from other sports to understand how they conceive strategy and decision-making in stressful situations.

Do you have an example in mind?

Yes: Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United, famous for its victories snatched in the « Fergie Time ». This wasn’t luck, but the result of a team capable of executing a precise plan in the final, physically and mentally grueling minutes… Developing superior match management skills – knowing how to think, adapt and execute under fatigue – is crucial for an elite judoka and requires specific training beyond just technical work.

Conversely, what specificities of judo could be useful to other disciplines, in your opinion?

The Hajime-Matte model, as a fundamental training framework, offers a structured and sequential approach to combat dynamics, easily transferable to other sports. Its structure – breaking down a continuous and complex interaction (from hajime to matte) into distinct and measurable phases – could thus benefit wrestling and Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Since these disciplines already share strong technical similarities, the DKK-TFI-WIN approach (gripping, throwing, ground) can be applied directly to them… The Hajime-Matte model can also apply to other combat sports like boxing or taekwondo. True, the techniques differ, but the principles of mobility (movement, distance management), preparation (feints, setups) and transition (standing-to-ground or standing-to-clinch) remain universal. The emphasis on technical super strength – the « trademark » – is an idea any coach can use to define an athlete’s brand and competitive edge… Ultimately, the Hajime-Matte model demonstrates how to create a highly focused, principle-based system that allows coaches to analyse performance, design constraint-based training, and develop tactical intelligence – a process that is valuable across any sport that involves sequential and high-pressure decision-making. – Interview by Anthony Diao, summer-autumn 2025. Illustrations: ©Nigel Donohue and Thomas Eustratiou-Diao/JudoAKD.

A .pdf of the Hajime-Matte model is available here.

A French version of this interview is available there.

More articles in English:

-

- JudoAKD#001 – Loïc Pietri – Pardon His French

- JudoAKD#002 – Emmanuelle Payet – This Island Within Herself

- JudoAKD#003 – Laure-Cathy Valente – Lyon, Third Generation

- JudoAKD#004 – Back to Celje

- JudoAKD#005 – Kevin Cao – Where Silences Have the Floor

- JudoAKD#006 – Frédéric Lecanu – Voice on Way

- JudoAKD#008 – Annett Böhm – Life is Lives

- JudoAKD#009 – Abderahmane Diao – Infinity of Destinies

- JudoAKD#010 – Paco Lozano – Eye of the Fighters

- JudoAKD#011 – Hans Van Essen – Mister JudoInside

- JudoAKD#021 – Benjamin Axus – Still Standing

- JudoAKD#022 – Romain Valadier-Picard – The Fire Next Time

- JudoAKD#023 – Andreea Chitu – She Remembers

- JudoAKD#024 – Malin Wilson – Come. See. Conquer.

- JudoAKD#025 – Antoine Valois-Fortier – The Constant Gardener

- JudoAKD#026 – Amandine Buchard – Status and Liberty

- JudoAKD#027 – Norbert Littkopf (1944-2024), by Annett Boehm

- JudoAKD#028 – Raffaele Toniolo – Bardonecchia, with Family

- JudoAKD#029 – Riner, Krpalek, Tasoev – More than Three Men

- JudoAKD#030 – Christa Deguchi and Kyle Reyes – A Thin Red and White Line

- JudoAKD#031 – Jimmy Pedro – United State of Mind

- JudoAKD#032 – Christophe Massina – Twenty Years Later

- JudoAKD#033 – Teddy Riner/Valentin Houinato – Two Dojos, Two Moods

- JudoAKD#034 – Anne-Fatoumata M’Baïro – Of Time and a Lifetime

- JudoAKD#035 – Nigel Donohue – « Your Time is Your Greatest Asset »

- JudoAKD#036 – Ahcène Goudjil – In the Beginning was Teaching

- JudoAKD#037 – Toma Nikiforov – The Kalashnikiforov Years

- JudoAKD#038 – Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard – The Rank of Big Sister

- JudoAKD#039 – Vitalie Gligor – « The Road Takes the One Who Walks »

- JudoAKD#040 – Joan-Benjamin Gaba and Inal Tasoev – Mindset Matters

- JudoAKD#041 – Pierre Neyra – About a Corner of France and Judo as It Is Taught There

- JudoAKD#042 – Theódoros Tselídis – Between Greater Caucasus and Aegean Sea

- JudoAKD#043 – Kim Polling – This Girl Was on Fire

- JudoAKD#044 – Kevin Cao (II) – In the Footsteps of Adrien Thevenet

- JudoAKD#046 – A History of Violence(s)

- JudoAKD#047 – Jigoro Kano Couldn’t Have Said It Better

More Replays in English:

- JudoAKDReplay#001 – Pawel Nastula – The Leftover (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#002 – Gévrise Emane – Turn Lead into Bronze (2020)

- JudoAKDReplay#003 – Lukas Krpalek – The Best Years of a Life (2019)

- JudoAKDReplay#004 – How Did Ezio Become Gamba? (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#005 – What’s up… Dimitri Dragin? (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#006 – Travis Stevens – « People forget about medals, only fighters remain » (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#007 – Sit and Talk with Tina Trstenjak and Clarisse Agbégnénou (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#008 – A Summer with Marti Malloy (2014)

- JudoAKDReplay#009 – Hasta Luego María Celia Laborde (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#010 – What’s Up… Dex Elmont? (2017)

And also :

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#01 – Episode 1/13 – Summer 2025

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#02 – Episode 2/13 – Autumn 2025

JudoAKD – Instagram – X (Twitter).