At the Senate, then behind closed doors. The 2025 All Saints’ Day weekend saw two significant events take place in Paris for anyone who has written and reflected on the theme of violence in sport in general, and in judo in particular. Taking the lead during these intense forty-eight hours through his association, Artémis Sport, seventh dan Patrick Roux delivers his concluding summary of the day after, an engagement made inevitable in light of the facts exposed. His mantra? He recently heard it from a minister’s mouth: “Work towards a shared truth, and have courage together.” Warning: Long article. – JudoAKD#046.

A French version of this article is available here.

« Un enfant, ça devient adulte que si tu lui laisses le temps – et c’est navrant » [« A child only becomes an adult if you give them time – and it’s heartbreaking »] raps MC Jean Gab’1 with firsthand knowledge in 2003 on his album Ma vie [My Life]. The muscular soloist with the cheeky Parisian street kid wit is then thirty-six years old, seven of which were spent in prison between France and Germany, as he would later recount in more detail in two essays published by Don Quichotte editions. Two floods of anecdotes that are anything but anecdotal, which excuse nothing but help understand a downward spiral: Sur la tombe de ma mère [On My Mother’s Grave] in 2013 and À l’Est [To the East] in 2015… His 2003 track, elevated by a thick, eighties loop from the all-too-rare Ol’Tenzano, recounts an adolescence—his own—spent at the DDASS (Direction départementale des affaires sanitaires et sociales) [Departmental Directorate of Health and Social Affairs]. The institution is supposed to protect profiles like his from the aftermath of a chaotic exit from childhood. Clearly, his experience wasn’t good. In memory of certain borderline elders and educators, he even drops this survival tip between communal showers and triple bunk beds conducive to discreet problematic behavior: « Your best friend is your fork. »

Autre gare, même train [Different station, same train]. « I believe my heart was that of an old lady and I feel younger today than I did back then, yes. » The person responding to us this way in spring 2013 is American judoka Kayla Harrison. Junior world champion in 2008, senior world champion in 2010, the student of Jimmy Pedro father and son and teammate of Marti Malloy and Travis Stevens is then twenty-two years old but her maturity is easily worth double that. During this interview, she reflects on a foundational act she took a few months earlier.

On November 8, 2011, the daily newspaper USA Today published a long profile of her. The U78kg athlete revealed that she had been sexually abused between the ages of thirteen and sixteen by her former coach Danny Doyle. This confession was granted to experienced journalist Vicki Michaelis with no other calculation than sincerity. « Because she asked the question and because I trusted her. A lot of people didn’t dare talk about it or bring the discussion to that territory. She did. I’d never met her before but I’d decided the time had come. I wanted to talk and she knew how to listen. »

The night before the article’s publication, Kayla is at a training camp in Japan. « I was super nervous. I was counting the days. My luck was being in a cycle of very hard training then. I’d come back exhausted and had no choice but to sleep, even if that night’s sleep wasn’t very restorative… »

On D-day, due to the time difference, she’s at the dormitory with Marti Malloy when her name appears in large letters on the screen. « I was reading the article on my computer and I was almost shaking. It’s very hard to be far from your base the day you reveal something so intimate… I was so afraid of being judged. Fortunately Marti kept telling me I’d made the right choice. She told me I’d shown courage and strength, that it could help other people speak up… Her words did me good. My sleep was peaceful that night. »

Nine months after this bombshell, Kayla Harrison pushes resilience to the point of becoming the first Olympic champion in the history of US judo in London. Four years later—four years dotted with other personal blows of fate that many wouldn’t have recovered from—she defends her title at the Rio Olympic Games. Then decides to bow out on that note, at twenty-six (she would later turn to MMA, with identical success). « I’m leaving happy with what I’ve accomplished in judo, » she told us at the time, her voice still hoarse from the emotions she’d experienced. « It’s time for me to continue this work beyond the mat and, why not, try to change the world. So that every teenager understands one day that, at the end of the tunnel, there’s sometimes a gold medal—or even two. »

Day One – There’s a Time To Fall and a Time to Rise Again.

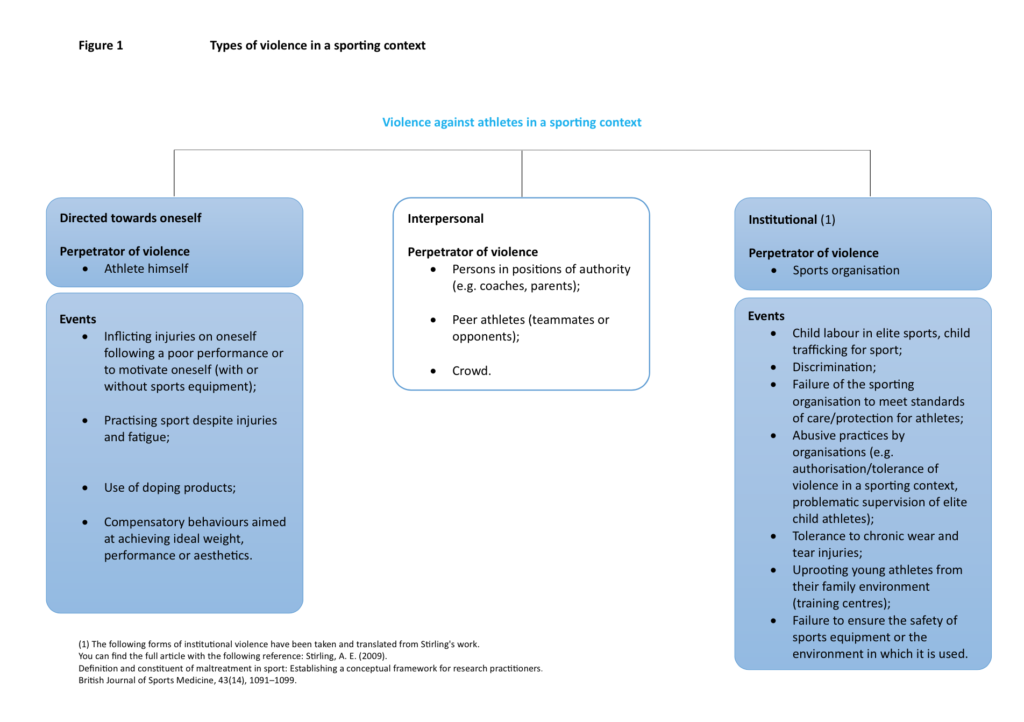

Paris, Palais du Luxembourg, Friday, October 31, 2025. The Medicis room of the Senate hosts a symposium dedicated to violence in sport, subtitled « Where do we stand, one year after the Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games and the release of the report on failings in the sports world? » It’s coordinated by Véronique Guillotin, senator from Meurthe-et-Moselle, also a doctor and third dan in judo. The event is moderated by Muriel Réus, president of the association Femmes avec… [Women with…], member of the High Council for Equality between Women and Men and co-chair of the commission for Fighting Stereotypes and the Gendered Distribution of Social Roles. « Sport, in the collective imagination, embodies strength, loyalty, respect for rules and the body. But it’s also, still too often, the theater of inequalities, of physical, moral, and sexual violence, that damage lives, ambitions, and talents, » she establishes from the outset.

Marina Ferrari, Minister of Sports, Youth and Community Life since the cabinet reshuffle that occurred three weeks earlier, declares this to be her very first public address on this topic. She’s the first of fifteen speakers who will take turns before the hushed 127-seat hemicycle that’s almost completely full, for two round tables and one (too) brief legal interlude among other things. « Filling the Medicis room on a Friday afternoon, I haven’t seen that often and I’ve been at the Senate for twenty-three years, in one way or another, » Olivia Richard will comment later, senator representing French citizens living abroad, member of the delegation for women’s rights and equality of opportunity between men and women.

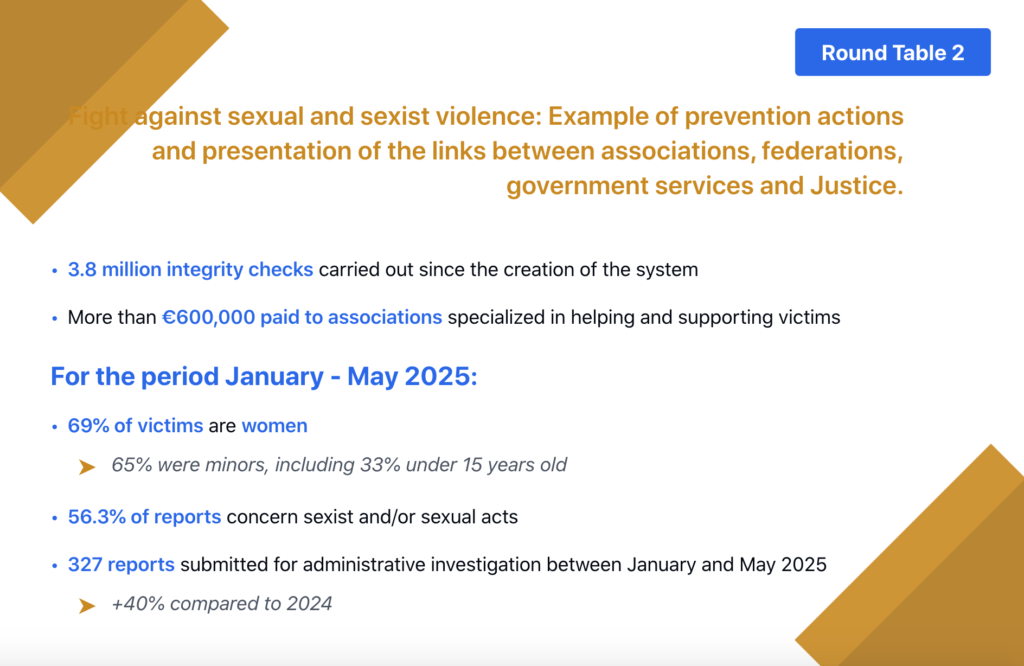

Reminder of the creation in December 2019 of the Signal-Sports reporting unit (« 2,062 reports processed by departmental services, 992 administrative measures taken by departmental prefects to remove accused individuals »), background checks (800 disqualification measures issued out of 4.2 million verifications carried out, according to the minister), prevention, training, gender parity issues since the law of March 2, 2022: the multiplication of public statements and articles on this theme since the turning point of winter 2020 has made these terms—once reserved for the four walls of ministries and departmental directorates—familiar to our ears. The two watchwords? « Understand and act, » frames Senator Véronique Guillotin.

Winter 2020? It was marked in quick succession by the publication at the end of 2019 of Le revers de la médaille [The Flipside of the Medal], an investigation by Daphné Gastaldi and Mathieu Martinière from the Disclose collective of journalists, cataloging seventy-seven cases across twenty-eight sports disciplines over eight months; then the coordinated launch with her co-author Emmanuelle Anizon from the weekly L’Obs of Sarah Abitbol’s book Un si long silence [Such a long silence], published by Plon editions. The former European and world medalist in figure skating recounted the rapes inflicted during her adolescence by her coach, and the three wise monkeys-style reactions (said nothing, saw nothing, heard nothing) from the governing bodies once they were contacted.

Week after week, like a remake of the #MeToo wildfire in the film world in fall 2017, tongues begin to loosen from one discipline to another. The trauma is collective, protean, considerable. The human toll, obviously, had been festering and is exponential. It quickly becomes unthinkable to send it back to the Bermuda Triangle where it had been contained until then. Daphné Gastaldi, during a talk at the end of January 2020 at the Lyon Press Club, draws a parallel between the world of sport and that of the Church, which her collective had also investigated several years earlier. « In both cases, the figure of the priest, like that of the coach, constitutes these authority figures to whom parents entrust their child with complete confidence. The betrayal of this trust and the general denial surrounding it are another common point between the two investigations we’ve successively conducted. »

The lockdown, and the introspection it imposes, further amplifies the momentum that’s beginning. It’s at this moment that the first exchanges on this theme with Patrick Roux begin. The former European judo champion, successive coach over three decades of the French, British, and Russian teams, has long disagreed with practices observed across the thousands of tatamis he’s stepped on. These dysfunctions—he wants them to stop. But he knows from experience that if no one tackles it, nothing will change. The system is too intertwined, too insular, too self-satisfied to risk it on its own. The first video calls also include Hector Marino and a fourth person with raw sensitivity, unfortunately since deceased. These meetings are an authentic call-to-action.

For my part, I keep in mind a cryptic message received from a Japanese contact. It’s early 2013. With colleagues from the French bimonthly L’Esprit du judo, we’ve just wrapped up several weeks of investigation around the post-London Olympics aggiornamento underway in Japan, to end a culture of violence and humiliation tolerated too long in the archipelago’s dojos. The testimonies and figures collected are staggering. The solutions outlined, a revolution… When the magazine came out, one of the many contacts consulted there sent me a message that would haunt me for a long time: « Extraordinary work. I hope you’ll treat the topic with the same intensity if one day such cases were to break out in France. » It’s said in the Japanese way, seemingly casual. But it’s said.

In this winter of 2020, these words come back to me. The promise had been internal until then. The time has come to honor it. It will take time because, as the 2013 message theorized implicitly, journalistic reluctance indeed grows with the geographical proximity of touchy subjects. The obstacles encountered are economic, emotional. Intimate perhaps, sometimes. Everyone has their biases, loyalties, and contingencies. There’s no stone to throw here.

The exchanges with Patrick Roux—and many others—continue. They’re regular, documented, urgent. Without return. They’ll lead to the publication, in October 2021, of a long investigation written with four hands with the courageous Guillaume Gendron in the French daily Libération. Necessary work given a discipline—judo—where, as in many others and under our latitudes this time, too many educators confuse rectitude with rigidity, proximity with perversity, martial pedagogy with deadly verticality.

The article’s publication opens another Pandora’s box. That of confessions, first in half-words then increasingly frankly, from other affected people. Yesterday, the day before, thirty years ago sometimes. People who’ve done everything to forget but whose sutures often end up cracking, especially from exposure to other victims’ testimonies. We journalists are custodians of these pains. Time will tell if those who’ve entrusted them to us—and still do—feel ready one day to make these terrible accounts heard by a wider circle. For themselves or for others. The journey, the decision, all of that belongs to them. In the meantime they know we’re here. And that while we owe the truth to our readers, we must also ensure the words used are not boomerangs. That they’re written neither too soon nor too late. Write accurately and when the time comes. In trust and in conscience. In short, we won’t betray them.

Casting a shadow over any debate on the question, the parliamentary report of December 19, 2023 submitted on behalf of the Commission of Inquiry relating to « the identification of operational failings within French sports federations, the sports movement and sports world governance bodies insofar as they have public service delegation. » From July to November 2023, one hundred ninety-three people (victims, journalists, representatives of sports federations) were heard for one hundred thirty hours by chair Béatrice Bellamy and rapporteur Sabrina Sebaihi. A total of sixty-two recommendations « for an ethical and democratic shock » were drawn from it, aimed at ending violence, omerta and cronyism in sport. A welcome beginning delivered just in time for the host nation of the following summer’s Olympic and Paralympic Games. But a beginning whose reach has since been deemed too limited by many involved actors. Hence the importance of this booster shot nearly two years after the hearings ended.

« You know who I am. You know what I represent. » Back to the Senate. Standing, without notes, Catherine Moyon de Baecque reflects on the double punishment experienced in her flesh in the French athletics team in the early nineties. The assaults suffered. The impunity of the perpetrators. The aftermath, visible and less visible. « Sourire devant, souffrir dedans » [« Smile on the outside, suffer on the inside »] as François Feldman sang at the same time. The precedence of her testimony earns her the more than symbolic status of first French high-level athlete to have broken the law of silence. « Sport isn’t this, » breathes the woman who from 2021 to 2025 was president of the French National Olympic and Sports Committee (CNOSF) Commission for Fighting Sexual Violence and Discrimination in Sport, and is today ambassador and expert at the Council of Europe for the protection of children in sport.

« I am this statistic […]: one child in seven. One girl in five. One high-level athlete in three. » The woman who succeeds her standing at the podium of the Medicis room is Angélique Cauchy. In fall 2024, the former tennis player published Si un jour quelqu’un te fait du mal [If one day someone hurts you] with Stock editions. A book written « for the seven million children in clubs. » For her son, too. « So he’ll be neither victim nor aggressor. » To forgive herself for not managing to speak in time when she was regularly sexually abused by her coach at the time, her silence having indirectly allowed him to prey on other teenage girls. « I know, but he brings us titles » will be the only response received when confiding in the adult world… Guest at the Sport, Literature and Cinema Festival organized at the end of January 2025 at the Institut Lumière in Lyon, the now general director of the association Rebond went into more detail there about the origin of her inability to speak: the memory of her father’s promise to « put a bullet between the eyes of anyone daring to touch a hair on his daughters’ heads, even if it meant going to jail afterwards. » A warning that, despite the overprotective appearance of its statement, would paralyze her when it came to reporting the assaults suffered, terrified as she was of imagining her father ending up in prison because of her « fault »… « I owe it to the little girl I was and thanks to whom I’m still alive. […] And even if I surely died a little at twelve, today I like to think I’m lucky because ultimately I’ll die twice. […] We have only one thing in common, it’s that we’ve all been children. »

It’s not easy to follow on after these testimonies. Especially as they echo an informal discussion a few months earlier in Lyon, on the occasion of a conference by Isabelle Demongeot. The former tennis player, author in 2007 of the terrible Service volé – Une championne rompt le silence [Stolen Serve – A Champion Breaks the Silence] published by Michel Lafon, was then on tour for the publication by éditions Les Sportives of Du silence brisé à la réhabilitation, 17 ans après [From Broken Silence to Rehabilitation, 17 Years Later], an expanded version of this pioneering story. Meeting her one-on-one, half an hour before the conference began, gave an idea of the extent of certain scars and the incessant stabs received since then as judicial delays, avoidance strategies and, worse, oblivion mounted. A reminder too of our responsibility as journalists to strive to rise to the level of such stakes.

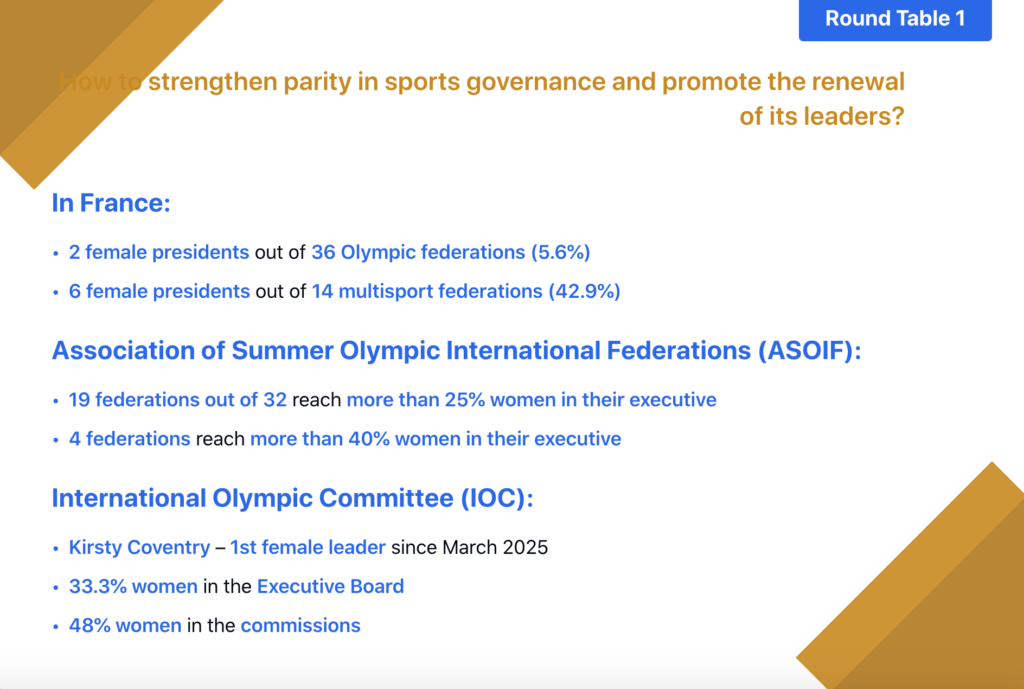

It’s not easy to follow on after these testimonies, then. Yet that’s the objective of the first of two roundtables opening just behind. « How can we strengthen parity in sports governance and promote the renewal of its leaders? » A substantial menu, unfortunately almost too copious to allow getting to the bottom of things in the allotted time. One certainty: « There was a before and after 2020 » for Isabelle Jouin, president of the French Hockey Federation from 2021 to 2024. The issue of parity rings as obvious for this leader who came from the business world and who would have her eyes widened upon arriving in a milieu of dated certainties. Consanguinity vs. diversity, resistance vs. cooperation, interdisciplinarity, lobbying, the notion of role model, aftereffects of labels like « tomboy » or « you’re not strong enough. » « The day when a man calls out or sanctions another man for deviant or sexist behavior, in public, well perhaps we will have gained a little ground, » believes Virginie Steinbach, psychoanalyst and consultant at INSEP in the training program for senior sports executives.

For Marielle Vicet, doctor in psychopathology and psychoanalysis, president of the national association Stop aux violences sexuelles [Stop Sexual Violence], it’s important not to fall into the trap of hyperperformance. « Women have nothing to prove. It’s more about a rise in consciousness than a rise in competence. » For her, « the divide is too extreme in our society, and it’s in our best interest to work with it, together, women and men. We have the noble task of preserving life. That of allowing everyone to express themselves in their feminine and in their masculine. Respecting the sacred, this intrinsic dimension of being. That’s the true power to bring forth beauty and goodness – these values connect women and men. And it’s not only women’s fight, but it’s the fight for freedom in our society. Respect for everyone, whether you’re a woman or a man. Every citizen has the right to be protected. »

And she continues: « Intelligence and courage lie in connection. This connection that brings people together requires vigilance from women to take their place, but also from men to make room for women. » Yet « where women make a mistake is when they behave like men and imitate their flaws. » A rare height of vision, therefore potentially divisive. Hearing this awakens the memory of the singular message of the film Tár by filmmaker Todd Field, where a female orchestra conductor exercises abnormal control over those around her, both male and female. The work, released in 2022, reminds the viewer that violence in interpersonal relationships is not solely a matter of sex. It can – must? – also be analyzed in light of social class and power dynamics. To support his demonstration, the director makes the deliberate choice to shake up viewers’ habits by beginning the film with… its end credits – that moment when the names of technicians scroll by that no one usually reads, even though without them the work doesn’t exist. A strong gesture from a subtle and rare filmmaker (three feature films in twenty years, each going against the ready-made thinking of its time), and a political as well as universal analytical framework that invites us to question the tenacious preconceptions arising from our own blinders.

After addressing questions of salary equity or parenthood through notably the example of inspiring practices at the Paris Opera, several hands go up in the room to share experiences or feelings from INSEP or from the worlds of skiing, karate, judo, canoe-kayak or even tech. Questions about resources, staffs, legislative levers, sisterhood, recipes, media narrative, uniforms (with the example of women’s beach volleyball, field hockey or female tennis players) or parity in commissions are raised.

In judo, this theme brings us back to the recent evolution of a nation like Georgia. Having become almost unbeatable during men’s team events in the Olympic cycle preceding Rio 2016, the country with Saint George’s cross suffered a terrible setback from the start of the following cycle. The cause? The introduction of mixed team events (three women and three men). This new situation laid bare the shortcomings of a nation culturally accustomed to betting on its strong men alone. A blessing in disguise: less than three years later, in autumn 2019, the U57kg Eteri Liparteliani became the country’s first woman to be crowned successively at European and world junior levels as well as at the U23 European Championships. An unprecedented tight grouping collected over fifty days flat. An individual peak she would reach again in 2025 by winning the senior world title – a first, there too. In teams, Georgia won its first world medals in mixed teams in 2023 in Doha then in 2024 in Abu Dhabi, before the absolute triumph of 2025 with the European then world titles in Podgorica then Budapest. « Where there’s a will, there’s a way, » to use the expression employed by Magali Baton, general secretary of the French Judo Federation, during her remarks in the course of these exchanges.

This section concluded, it’s time for the legal part. It brings together Maître Sarra Saïdi, lawyer at the Paris and Ontario bars, specializing in international arbitration and sports law, and Maître Tatiana Vassine, also a lawyer at the Paris bar, sports agent lawyer, publishing director, teacher and writer. The purpose of the exchange is to take stock of the law in France, compare it with what’s being done in Canada, and explore the prospects for evolution of this « blind spot » that these themes constitute within many sports organizations. Between criminal, administrative and disciplinary procedures, the exchange lays bare the extreme vulnerability of victims under positive French law, reduced to the status of David against Goliath when they find themselves confronted with the discretionary power of federations, especially when those federations see their own governance or « groups of friends » close to them called into question…

Cause for despair? Not really. By observing what’s being done across the Atlantic, the exchange offers new perspectives. It even makes it possible to definitively corner the question of conflicts of interest. According to the lawyer, canadian sport indeed made the choice in 2019 to separate ordinary sports management from aspects more related to the question of its integrity. Procedures are outsourced and entrusted to the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport, an independent agency already authorized to deal with doping and manipulation of sporting competitions. This choice opens up entirely different horizons, Maître Saïdi indeed explains, starting with moving away from the « family » management model so often criticized in the French model. Pooling of resources, creation of a one-stop shop allowing the victim to be kept informed, adoption of a universal code of prohibited behaviors, return of transparency at all levels… Obviously, not everything happens with the wave of a magic wand and many obstacles remain to be removed. To get out of this gray zone, the jurist mentions the leverage of name and shame, the umbrella action of the International Olympic Committee, the existence of multidisciplinary research chairs and a database cross-referencing press clippings and court decisions over thirty years, making it easier to identify this or that typical modus operandi… A confirmation, once again, of the maple leaf country’s acuity when it comes to projecting over the long term while leaving as few people as possible by the wayside.

How to avoid « secondary victimization, » that is, this deafening silence that too often follows the filing of a complaint or report? « It’s up to the ministry to take its responsibilities, » answers Maître Vassine, because « otherwise it’s impunity, and impunity reinforces deviant behaviors. » Observation of the lack of listening in conventional justice due to lack of time, observation also of the lead blanket that falls on the coach once accused, importance of having the victim accompanied by a specialized lawyer, necessity of protecting whistleblowers… « Speaking out means exposing yourself to prosecution and that, that’s not acceptable. » On this last point, no one has forgotten the hostility encountered in their respective professional circles by footballer Jacques Glassmann right after the OM-VA corruption affair that his speaking out triggered in 1993, or cyclist Christophe Bassons, forced to leave the 1999 Tour de France following his columns in the daily newspaper L’Humanité, deemed tendentious by part of the peloton regarding the doping practices of the microcosm…

These frameworks having been set, the audience is burning to take part in the discussion. More consideration for academic research, parallel with the fight against doping where often only the athlete pays the price while in matters of violence there’s a whole chain to analyze… Above all, a psychologist in the audience points out the considerable room for improvement that remains around the Signal-Sport tool. The report generates an expectation and the waiting happens in a silence and solitude that are complicated to manage, especially when the victim is led in the meantime to return to their club or to interact with their federation. « We must free speech, but we must also protect it, » insists Maître Vassine.

The second roundtable takes things up a notch. Roxana Maracineanu, Minister of Sports then delegated Minister in charge of Sports from September 2018 to May 2022 – that is, at the height of French sport’s introspection – demonstrates a three-hundred-sixty-degree knowledge of the files and issues. The former world swimming champion recalls the character checks put in place in a nation where the model of three and a half million volunteers is « perhaps worth reexamining ».

She also emphasizes the decisive aspect constituted by the rapprochement with a structure such as the association Colosse aux pieds d’argile [Colossus with Feet of Clay], or the importance of ministerial continuity given the scale of the projects initiated. « [If] there’s all this work, [it’s] because we started. Because we’re in it. In other fields we’re not there yet. We haven’t even started yet! »

Perrine Fuchs, inspector of youth and sports and head of the Public Protection office at the Ministry of Sports, Youth and Community Life, confirms that considerable housekeeping is underway among the approximately « nine hundred people [who] were registered in the Fijais [file of perpetrators of sexual or violent offenses] and were active in sports clubs. Most of them were leaders. » She also points out the difference in progress from one federation to another as well as the limited human resources deployed to allow cases to move forward – « there are four of them, my colleagues, to handle a volume of two thousand reports from Signal-Sport over the last five years, in addition to one or two investigators per department. »

In 2024 alone, prefects took one hundred and forty-one emergency measures – most being « made permanent. » Concretely, « the departmental prefect takes an administrative police decision, that is an order prohibiting practice, which will have the effect that the person will no longer have the right to go to the club, to intervene, to supervise, to lead activities, to be a leader, to be a referee… The only thing the person will have the right to do is practice sports since we don’t yet have the right to prohibit people from doing sports. » And to recall this paradox so painful for victims to live with: « We can only inform the accused person of the progress of a procedure. […] Legally, for example, we cannot publish prefectural prohibitions on practice. »

It’s Patrick Roux‘s turn to speak. Since the launch in autumn 2021 of his association Artémis Sport – in reference to « a Greek goddess whose one of whose powers is to heal, » he told his close team at the time – then the publication in spring 2023 by éditions Dunod of his essay Le revers de nos médailles (The Other Side of Our Medals), one of the most respected educators on the judo planet has become essential on this subject. The only man called to the stage this Friday, he prepared this intervention with the same meticulous care as when he competed – one world medal, five European podiums including one title and a fifth place at the Seoul Olympics, as a reminder.

« In this room, I have many colleagues who are sports teachers or state agents. And I’d like to highlight one thing, which is that we share the same republican values – I’m convinced of it. And it’s one of the reasons why this subject deeply shocks us. » For him, since the awarding to the city of Atlanta of the centennial Olympics in 1996 rather than to the cradle city of Athens, sport no longer hides the fact that it has become a business. A turning point that in his view makes « the preaching around sports values » almost obsolete. « Yet today we have the opportunity to be exemplary. »

While he measures the distance covered since the more than twenty years he’s been alert to this subject, « there are still many gray areas » but « we’re here to tell each other about real life. » Among the challenges that must not be avoided: financial support and « recognition of the truth that victims carry. » Sexist and sexual violence, influence peddling, misuse of corporate assets: for him everything overlaps. And he cites the sworn statements of certain French sport leaders during the parliamentary commission of autumn 2023, to which he himself was also invited to testify.

Patrick Roux’s questions are hard-hitting: « Who, politically, is going to take a position? » And later: « We still don’t know what happened to the seven reports for perjury sent to the Paris Prosecutor’s Office during the parliamentary inquiry commission. »

He’s starting to clearly understand the contours of the glass ceiling. « The problem is that we only hit the fall guys. We need to go after people of notoriety in sport: federation presidents, leaders, people who may have been ministers… This whole very high-level sphere, it’s very complicated. There, immediately, there are interferences. » The current system? « It asks cops and robbers to gather in the same room to analyze, observe and decide on the most difficult situations. » To counter this « limited » scope, Roxana Maracineanu proposes creating « a supra-federal layer » – like an echo of the Canadian approaches mentioned earlier by Maître Saïdi.

The next speaker is Dr. Hélène Romano, doctor in psychopathology, in private law and criminal sciences, and essayist. Pushing reflection over the long term, she who, twenty-five years earlier, when about to defend her thesis on « the care of child victims of sexual violence in the school environment » had used the term « cluster bomb in the life of a child victim, » warns of the decompensation phenomenon that can seize victims many years after the facts, when they become parents or when their child reaches the age they were at the time of said facts, for example. She emphasizes listening, delicacy and measuring the importance of the central role of the body for an athlete, both as a support for performance and as the first receptacle of violence. Sensory traumatic revivals, incestuous dynamics, notion of discredited authority figure, of insular community that reinforces a sense of guilt… « When the one who assaults turns out to also be a parent, it durably destructures. To survive, the child needs an adult who tells them: I believe you, I hear you and I’m here. » There is no reconstruction without recognition – and, above all, « this listening re-humanizes. »

These last words echo the CCeSoir [It’s Tonight] program on France 4 which, on the following November 12th, would see Judge Edouard Durand define the denial of those around the victim as manifesting itself in sentences like « it doesn’t exist, » « it’s not possible, » « it’s not true, » « it’s not serious, » « it doesn’t concern me. » Before, further on, making this terrible statement: « We had shown at the Ciivise (Independent Commission on Incest and Sexual Violence Against Children, which he co-chaired from 2021 to 2023, editor’s note) that, when a child reveals sexual violence, when a child comes to see an adult saying ‘I’m a victim of incest,’ there are three main types of possible responses. First response, which we called positive social support, is: ‘I believe you, I’ll protect you.’ Second type of response is negative social support: ‘I believe you, but that’s all’ – as if that were enough. Third type of response is the absence of social support: ‘You’re lying.’ Well, out of a hundred children who report sexual violence, eight will hear ‘I believe you and I’ll protect you.’ Eight percent. Ninety-two percent of these children will not receive positive social support. And this responsibility doesn’t only rest on the role of this mother who has only two bad choices: either ‘I believe my child, I protect them, and I’ll be accused of manipulating them,’ or ‘I do nothing and I’ll be accused of being complicit.’ It doesn’t only rest on the shoulders of this teacher or this educator… It’s a public policy. »

And the magistrate continues: « I accompanied doctors to disciplinary chambers of the Medical Board, who were accused of having made a report. But I was ashamed for my country!… We know that there are protective mothers who are only doing their duty, and who find themselves being accused. And that’s a public policy. Our institutions – the State, through law from my point of view – must be capable of saying: when a child tells you ‘you asked me on TV to say if I’m a victim,’ [since] there was a campaign to that effect, well if the child trusts us, here’s what you must answer them. Period: here’s what you must answer them. And let this be a rule. […] Otherwise we continue to tell children: ‘We prefer that you don’t talk about it, it doesn’t interest us.’ But not halfway. Because we put them in danger. »

An excerpt from the educational film Lilia by Charlène Favier (author of the acclaimed Slalom in 2020, inspired by her painful experience in the skiing world) is screened to raise awareness of this issue as part of the school curriculum’s education program. The film is supported by Miprof (the Interministerial Mission for the Protection of Women against Violence and the Fight against Human Trafficking), whose Secretary General has been Roxana Maracineanu since 2023.

The microphone circulates around the room. A mother, present with her daughter, explains that the latter recently learned she had to submit a new written report application three years after finally deciding to dare to make the first one. Three years of waiting in vain that today cause legitimate confusion and will lead her to discuss it at the end of the conference with Perrine Fuchs, among others. « Whistleblowers are always on mined ground. This risks reinforcing the feeling of impunity, » confirms Alexandra Soriano, a judoka and whistleblower herself in the early 2000s.

A testimony about firefighters, an evocation of the remarkable background work of journalist Pierre-Emmanuel Luneau-Dorignac or the complete overhaul of the Japanese judo pedagogical model following the London Olympics, a warning about the escalating reality of digital violence via the inappropriate solicitations that adolescents are increasingly facing—and it is time to conclude the conference with a solemn address by Amélie Oudéa-Castera, President of the French National Olympic and Sports Committee and Minister of Sports and the Olympic and Paralympic Games from 2022 to 2024. « Because this fight for a more ethical, cleaner, safer sport is a commitment for all of us. »

Day Two – The Return to Innocence Lost.

Saturday, 1 November 2025, in a conference room in the basement of a hotel near Montparnasse train station. Patrick Roux opens this second seminar/support group of the Artémis Sport association, which he has chaired since its creation in the autumn of 2021. At his side is Karine Repérant, sports psychologist frequently cited in his book Le Revers de nos médailles. There are thirteen of us around the table: teenagers, adults, parents. And a journalist, of course. The sports represented are judo, gymnastics, fencing and climbing. The lines that follow will ensure that the people present cannot be identified, with a few notable exceptions.

“A year ago, we organised the association’s first seminar,” Patrick Roux begins. “Experience shows that you come out of it better than you were before.” Beside him, Karine Repérant sets the framework for the discussion: “Your truth is your lived experience. We are here to listen, not to judge. You are free to leave the room whenever you want.”

A first round of introductions allows each person to present themselves to the others and state their expectations for the day ahead. And, for those who were at the Senate conference the day before, to express how they feel with a few hours’ perspective. Two mother-daughter pairs are seated side by side. Hearing these teenage girls, in this context, in front of people they do not know, put words to the violations they suffered at an age when life should, in principle, be nothing but momentum and enthusiasm, is an experience that cannot leave anyone untouched. Seeing a mother’s tears rise as her daughter, just to her right, unfolds a story no parent ever wishes to hear says everything about the sense of powerlessness and guilt that can gnaw at a parent who realizes, after the fact, that their only “mistake” was entrusting the wrong people with guiding their child in the pursuit of her childhood dream. It will take time to trust again. At times, a damp silence fills the room. Facing the adolescent, coming from another sport, a participant encourages her: “I’ve been where you are last year. The road is long, but I can tell you that today, things are much better than they were a year ago.”

Each participant recognizes a part of their own experience in the stories shared by the others. For Alexandra Soriano — a pillar of Artémis, a member of the federal board, and the elected official in charge of para-judo — the night was difficult. “I don’t often have tears in my eyes, but yesterday I did. I didn’t sleep last night because I feel that even though I raised the alarm about these abuses twenty-five years ago, I still haven’t managed to make things change. [To the teenage girl who has just moved the whole room with her story]: your coach, I reported him twenty-five years ago. There is so much inertia. It’s as if common law doesn’t apply to the world of sport. I’ve seen girls cut themselves during training. And I’ve also seen how the awarding of grades — because it leads to better social recognition — becomes both a lever and a means of pressure… If I ran for election at the Federation, it was to try to make things move. We need to be present at every level.”

“Today I don’t even want my aggressor to apologize,” continues another participant. “I was seeking revenge. It was when I decided to give up that quest that my healing — and my family’s healing — began.” Because the surrounding environment is a crucial part of the equation. Echoing the previous day’s discussions and the magistrate’s upcoming remarks transcribed earlier: “a supportive environment is part of the solution; a non-supportive environment is part of the problem.”

Sitting at the table, the father of a teenage girl recounts the abyss of questions into which he was plunged after the recent revelation of the groping his daughter had suffered a few weeks earlier. First, the feeling of having “no one to talk to.” Then, once he found those he believed were the right people, the insidious mechanism of guilt-tripping he received in return — “Be careful, because if you say anything wrong, there have already been teachers who committed suicide over similar cases.” Finally, the brutal realization that he himself had long been part of that same environment. A world where everyone knows everything and everyone remains silent — “All those guys, I used to say hello to them.” Disgust, regret for having exposed his daughter despite the signs he didn’t see or — worse — refused to see… The anger is palpable.

“Don’t judge yourself,” replies Karine Repérant, broadening the message to all parents. “You did what you could, what you thought was best to help your children achieve their dream… [To the children] I sometimes hear people say, ‘It’s not up to the victim to leave.’ Well, yes, it is. You only have one life. Wherever you’re being hurt, don’t stay.”

Easier said than done, as reminded by the man who had already attended the previous year and who, just minutes earlier, explained how far he had come in a year. His account of the humiliation he endured from a well-established teacher is staggering. The reaction from his regional league can be summed up in two words: “We know.” With hindsight, he regrets not insisting more to sound the alarm, but he dealt with the most urgent: “I saved myself first. It won’t erase what happened, but you have to keep going.” For a long time, he took out his anger on his own children. Then the anger turned into sadness, and the sadness into depression. Psychological follow-up and EMDR [Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing] still help him climb back up today.

“I was the easy girl, I was the running gag,” continues another participant. Control, insistent and inappropriate questions about sexuality, breakdown, psychosomatic symptoms, the discovery of institutional violence — “you think everything will go fast, but actually, no.” And this bitter observation: “There are the abusers, and there are those who say nothing. Those ones, they don’t make me dream.” Only the Paris Olympics reignited her desire to reconnect with her sport. Now a Master’s student, she acknowledges finding in her studies the same taste for challenge that sport once gave her.

“It’s not by telling yourself ‘I’m fine’ that things get better,” clarifies Karine Repérant. “If you don’t work on yourself, you’ll spend your whole life showing others that they still have that power over you. And there’s a moment in life when all of this gets reactivated — parenthood. Each of you can already decide to be the best for yourselves, not in relation to others.”

Lockdown also marked a peak of toxicity for certain relationships, especially when sport and couple life overlap. “I walked straight into the wolf’s mouth,” admits a woman nearby. “Pretty quickly, he started treating me with silence, until eventually telling me I was always in the way.” The tension became physical — to the point where a nurse once told her: “If you’re dead, you won’t save anyone. When you’re better, you’ll go back to help the wounded. But first, save yourself.”

At this point in the round table, the ice is broken. Everyone knows who’s who. Karine Repérant and Patrick Roux then take the lead again. The goal is to reiterate a few constants: procedures, defendants, victim or witness status (and the implications of this choice regarding the ambiguity sometimes maintained by the opposing party)…

Regarding the aggressor, Karine Repérant distinguishes three profiles. First, the one with deviant behavior. It’s difficult to see them coming for anyone who doesn’t know their past, especially since they are generally appreciated for their coaching work… The second profile is that of people who have experienced difficult things and feel the need to reproduce them to survive, since it gives them the feeling of… validating their own experience. « If they hadn’t been in the sports world, perhaps no one would have ever heard of them. » Finally, the third profile concerns those people whose fantasies eventually take precedence over values, even to the point of acting upon them. Combined with the cult of winning associated with competitive sports and its corollary—the quest for admiration and blind trust—the whole gives rise to these relationships marked by denial. On this point, Karine Repérant does not mince words: « If you get out of victim status, you will no longer be a magnet for a-holes. »

What about restorative justice, as recently popularized in cinema by Jeanne Herry’s film All Your Faces [Je verrai toujours vos visages] or, in a completely different context, initiatives such as the Truth and Reconciliation commissions in South Africa or the Rwandan village community courts that became central to the challenges of (re)living together post-1994 genocide? « It would be good, yes, if those accused heard the things they made others live through, » Karine Repérant agrees. « Things are evolving in this direction in Spain, even if it remains difficult to envision for sexual violence. »

What about forgiveness as well? A vast subject. « Forgiveness does allow you to drop the issue, to move on, » Karine Repérant continues. « It’s not excusing or explaining. It’s ‘I forgive you for having passed through my life,’ putting the story in the past. It’s ‘I have suffered enough’… » There is another word, which is acceptance. Can one accept and not forgive? All of this connects with resilience… And the phrase that went viral from Antoine Leiris following the disappearance of his partner on November 13, 2015, during the Bataclan attacks: « You will not have my hatred. »

The afternoon will notably see the two youngest participants take the time to tell the audience their stories. A moment all the more solemn because, in both cases, their mothers are seated by their sides.

Karine Repérant suddenly interrupted the first sequence. The reason? The fact that several adults, with good intentions, came to complete the teenager’s account by putting it into perspective with legal and technical considerations. The shift brought tears to the psychologist’s eyes: « But can’t you give her the time to finish what she has to say? This is her moment! Let her have the space to have lived it! »…

Back from a necessary and beneficial fresh air break for everyone, attention is now total for listening to the story of the second teenager, whose mother by her side teaches the same discipline. Overt ostracism during training, fondling between two doors by a supervisor at the boarding school… The young girl literally stunned the audience during the final « calm-down » session with Karine Repérant. Gently, the psychologist asks her if she thinks she has said everything.

« I’ve said the main points, the teenager replies to her.

– The main points, Karine Repérant bounces back. That means there are still small points, then?

– There are still small points, yes…

– And why didn’t you say those small points?

– Because otherwise Mom will really worry. »

Not a pair of eyes remained dry at the unexpected statement of this confession. And certainly not those of the mother in question, sitting beside her, whose chin trembled in silence. A few moments later, as the conversation resumed at the other end of the room, we would hear the same young girl discreetly turn to her mother and confess: « Actually, it’s Dad’s reaction that I’m most afraid of. »

This internalized self-censorship speaks volumes about the gap separating her at this moment from the spontaneity of kids her age. But the courage to express herself like this, despite or because of the heavy and tense atmosphere of the two days that have just passed, also says a lot about the perspectives that are now opening up for her by making, this time, the right encounters. Kintsugi perspectives—named after the Japanese method of repairing broken ceramics, porcelain, or earthenware, not by concealing the cracks, but on the contrary by enhancing them with gold powder. An authentic metaphor for patience and resilience that echoes the introductory remarks of Senator Véronique Guillotin at the previous day’s conference: « As a judoka, I want to share a simple conviction: strength is not domination, it is mastery. Authority is not arbitrariness, it is example. Courage is not denial, it is lucidity. » A lifetime will not be too much to measure the power and scope of these words.

Post-scriptum – Five Questions for Patrick Roux.

Front and center on both Friday and Saturday during this substantial weekend event, the former champion and former coach—now a trainer at the INSEP Training Center, responsible for sharing and optimizing experience—provides his assessment in his own way: thoughtful, precise, and well-reasoned.

Q1/5 – What positive points do you take away from the conference on October 31st?

First, we achieved the main objective. This goal was to bring the observations, analyses, and recommendations of the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CEP) report on the abuses and dysfunctions in the world of sport (federal bodies, ministry departments, CNOSF) back into the public eye and the media, political representation, and civil society spotlight.

Next, we were also able to ask very precise and concrete questions to the ministers, senators, and sports body representatives present. These questions demand answers, and we are waiting for them!

Finally, and this is essential, we embodied the convergence of struggles of associations from different worlds, and thus far beyond the world of sport. Representatives from Ciivise, France Victimes, Stop aux violences sexuelles (Marielle Vicet and Catherine Delahaye), Archipel Ciivise 1… All of this strengthens our messages when we recall that Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) is systemic violence that crosses all fields of society.

We must dare to ask the most difficult, the most unsettling questions: would you do this to your child? And if one day it happens to one of your children, how will you react? Another positive point is that victims of violence, sometimes very young, came to attend the conference. We feel they are increasingly able to speak out.

« We must dare to ask the most difficult, the most unsettling questions: would you do this to your child? And if one day it happens to one of your children, how will you react? »

This combination of facts and positive points allowed us to reaffirm to parliamentarians and ministers that we are facing a crucial societal challenge and that the State and public authorities must show citizens that they can trust in justice, public power, investigative means, and support mechanisms for victims and often vulnerable people. This is a social contract.

Q2/5 – What are the sticking points and areas for improvement at this stage?

Conversely to these positive points, there are still too many cases and situations where we can feel that things are stuck or blocked. We are still confronted with denial, negligence, and sometimes institutional silence, with the old playbook and bad practices from before 2020, let’s say, to set a marker.

If we analyze the figures given by the Ministry of Sports, we note that out of 2,064 reports, very few judicial procedures result in a sanction. Take, for example, those seven cases of reports for perjury by high-level sports leaders following their hearings before the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry. We have no news about these seven reports! We know nothing! And this, of course, gives an impression of impunity and even omerta.

There would, however, be an easy margin for progress to be made here. An opportunity to be exemplary. But since for the moment nothing seems to be happening, we get the impression of witnessing a return to grace for these major sports leaders who were singled out by the deputies who led the CEP. It must be remembered that crimes and offenses were at issue which allegedly had been suppressed since, in several cases, these leaders were criticized for their inaction, WHEREAS THEY SHOULD HAVE REPORTED THEM OR FILED ARTICLE 40 REPORTS.

The sticking points often result from this type of paradoxical situation.

People involved in the world of sport whom I know well tell me: « You see, I told you nothing would happen. » These are often people who don’t like these SGBV issues being discussed. First, because they have interests in not discussing them. For example, people who do business with, or within, the world of sport. It goes against the business, which remains very attached to the idealized image of sport and the values attributed to it, even if it’s fiction. In fact, they are part of the system.

But it’s also because of the historicity of bad habits, as the world of sport was built around 1901 association structures and very permissive practices with little control until recently. We see this clearly through the crises currently affecting certain federations, which are reported in major daily newspapers.

« Since the publication of this report at the beginning of 2024, and following the Paris Olympic Games, acts of violence, including those of a sexual nature and against minor victims, are not decreasing. In the first half of 2025, they were, on the contrary, up by 40% compared to 2024. »

I don’t know why, we have this impression that the Ministry of Sports is slow to react and that its responses are inconsistent. This is what Mr. Jean-Marc Sauvé, former President of the Council of State and of the Independent Commission on Sexual Abuse in the Church (CIASE), said. He severely condemned the reaction of public authorities, not hesitating to speak of hypocrisy and systemic failures, considering that here, people prefer to blind themselves to the extent of the harm and its consequences (Report Volume 1, page 32 Violence, omerta and self-serving circles in sport: 60 recommendations for an ethical and democratic shock).

It turns out, therefore, that the main sticking point is undoubtedly the French sports system itself. On page 33 of the same report already cited, Mr. Pierre-Alain Raphan, former Deputy and rapporteur of the bill aimed at democratizing sport in France, states: « That being said, sometimes there is a State that protects itself… I saw certain things and I told myself that the system had to be changed rather than attacking the men who diverted the system… »

In the following paragraph of the report, it is recalled that Sarah Abitbol had accused a minister of turning a blind eye to the rapes she was a victim of when he was in office. Yet, this same former minister is found among the members of the National Committee for Strengthening Ethics and Democratic Life in Sport, established in March 2023 by the minister then in office…

Since the publication of this report at the beginning of 2024, and following the Paris Olympic Games, acts of violence, including those of a sexual nature and against minor victims, are not decreasing. In the first half of 2025, they were, on the contrary, up by 40% compared to 2024.

With hindsight, we realize that the observations, analyses, and recommendations of the CEP 2023 report were not exaggerated at all! It was by no means a damning report, neither against sport nor against the federations. The French sports system made these types of statements as a countermeasure to defend itself again.

With the most recent cases and situations of violence, we have another opportunity to improve things and start changing the environment. Some recent facts are not time-barred. If you carefully read the investigative reports of journalists (Mediapart, Le Monde, L’Equipe, Liberation, Le Parisien, 20 minutes, etc.) and cross-reference this information with, on the one hand, the excerpts from the reports of the General Inspectorate of Education, Sport, and Research (IGERS) missions published in the CEP report, and also with the hearings of major sports leaders before this same CEP (they are public and broadcast on YouTube, Dailymotion, etc.), then you understand very well how this old, worn-out system works, and you also understand that it still works this way today.

As for us, leaders of SGBV associations who try to support victims, we receive calls from parents telling us that their victim daughter still does not know the date of their aggressor(s)’ trial, five years after the revelations, and that she is attempting suicide. Concerning the reports for perjury of these seven major French sports leaders and concerning the reforms of this old, rotten, and corrupt system, what can we answer them? It is time to pull ourselves together and take the bull by the horns!

Q3/5 – Regarding the Artemis Day on Saturday, 01/11, it’s a kind of miracle to see the discussion flow so freely among the participants. Is there a lot of preparatory work done beforehand? What are you most attentive to so that participants feel confident?

I think what you observed and felt is the result of the daily commitment of the people in our association. The people who have been with Artemis Sport since the beginning have all been deeply impacted in their lives by these phenomena, which are genuine societal issues.

Some are ex-victims of sexual and gender-based violence. Others are witnesses, whistleblowers, caregivers… All have, in a way, been through the fire because of these situations, their commitments, and the courageous choices they have made. People have almost set aside what they were doing before to focus on this fight, or it has integrated into their main occupation…

We have developed experiential know-how based on the concrete field situations we have lived through and encountered since the spring of 2020. I remember being audited sometimes at the beginning, in 2021 and 2022, by agents from the Departmental Services for Youth and Sports (SDJES) who were not trained at all. In fact, they discovered the situations during our auditions. We were almost training them! But what I consider most important is the contact and sometimes the meeting, the accompaniment of the victims and the situations. It’s like a flow; we are immersed, and we are constantly learning from the situations and by listening to the people concerned. It is more an emergent process than a programmatic one.

A key person who knows how to remind us of this is the psychologist Karine Repérant. In fact, the work is permanent. We live with these questions, these inquiries, this search for truth and solutions. More concretely, while we do suggest and propose that people participate in our seminars, we are primarily attentive to their journey. Most of those who participated had already traveled some distance on their own. People who participated in the first seminar came back and helped us facilitate and supervise the second. Other people have been supported for months and are now in a dynamic that seems very positive to us. They have left their victim status and have committed themselves in various ways to help others and fight against SGBV.

I think it is this whole dynamic and this lived experience that can create a climate of trust. But, once again, even if we constantly debrief, we learn from every encounter and every experience. We prepare beforehand with a kind of itinerary, but above all, you have to live the encounter live and adapt; it is rarely the same twice, and we do not seek to reproduce but rather to sense and understand.

Q4/5 – This is the structure’s second session of this kind. Are there any segments you changed between the 2024 session and the 2025 session? Conversely, are there invariants that ensure the success of such gatherings?

In 2024, although I had already done hundreds of hours of interviews, it was the first time we organized this seminar. I was a little stressed and kept thinking: what are we going to do if no one starts talking? Fortunately, once again, Karine Repérant was the resource person because she had supervised many such support groups…

There were eight participants, and I had planned a small « inclusion » as an icebreaker and for everyone to introduce themselves. Hardly had I given the microphone to the first person than she immediately began her story, which led to interactions with the other participants, and it didn’t stop all morning… So we immediately learned something! The need for people to tell their story, to speak their truth, is immense and so legitimate.

Among the indispensable invariants that make it possible are the ability and competence to listen, as well as confidentiality. The fact that it takes place « among peers » is also key: the participants, even if they don’t know each other, more or less intuit that the others have also experienced or been concerned by similar situations. Of course, this is primarily based on their own desire to share their experience and their story.

During the first two seminars, we had confirmation that although each participant had different histories and experiences, the painful experience and the feeling are quite similar. Furthermore, some had to censor their speech at one point or another in their journey, for fear of retaliation or simply due to a lack of support mechanisms and listening capacity. Sometimes, fear turns into anger, and these emotions resurface.

« The participants, even if they don’t know each other, more or less intuit that the others have also experienced or been concerned by similar situations. »

I do not wish to say more about these moments here. I only want to emphasize the importance of accompanying people over the long term, after they have spoken out and sometimes reported the violence they have experienced. It is indeed after this phase, after reporting and having the illusion of possible relief, that people too often find themselves alone and isolated, often excluded from their sports family, forced to leave their club or the training structure where they practiced… And they are too often struggling to obtain information on the progress of the investigations concerning them.

During our first seminar, beyond the stories told by the participants, we also asked this question: « How would you have wished for the world of sport (club, federation, ministry) to support you after you spoke out? » The concepts that came up most frequently were those of local liaison, national liaison, collaborative work, comprehensive support (educational, professional, psychological, financial, etc.), and training on… informing one’s own parents—since some couldn’t bring themselves to take that step.

Q5/5 – More generally, how have these five years of working on these themes confirmed long-held intuitions or, conversely, challenged your view on the teaching profession?

In fact, since the late nineties, and particularly with the Atlanta Games, the die was cast for me. The evolution of the discipline toward an Olympic sport had already consigned judo and its great educational objectives, if not to oblivion, at least to the basement. The sport-business finished the job by sending the educational objectives of sport and judo up to the attic.

You talk about long-held intuitions, and you’re right! When I was an athlete on the French national team in the early eighties, I gradually—and sometimes unconsciously—distanced myself from certain dominant practices or trends at the time. There were very diverse schools and clubs that welcomed high-level judokas. Some had the ambition to train and support complete judokas, who sought to understand and express judo, including in competition at the highest level. Others seemingly cared only about the result. I sometimes had the impression that they were overplaying the role of a provocateur, a stance made up of exaggeration and even outrageousness. For some, this was undoubtedly the case, but in all human groups, there are fragile people who interpret this kind of humor and transgression beyond certain limits very poorly. Clearly, when the structure or institution turns a blind eye to acts that are already offenses, one should not be surprised if a few individuals go much further.

At INSEP, in the late nineties, under the impetus of Director Michel Chauveau, the sports science department was rapidly developing. Researchers in psychology explored the personality traits of athletes. They sought to understand the working relationships between coaches and trainees. They had also identified a behavior they termed « hypercompetitiveness. » These were athletes so obsessed with a need for self-affirmation and success that they were (and are) capable of adopting deviant practices to achieve it (doping, cheating, violence, and intimidation). This « hypercompetitiveness » can be compared to an addiction. It primarily puts those who slide into these practices for very diverse reasons at risk.

The study also made links with risky practices that these athletes could also adopt outside of sport, in everyday life (reckless driving, driving while heavily intoxicated, incivility in public places, verbal, physical, spousal, sexual violence, etc.). Fortunately, these behaviors characterize only a minority of athletes. But some, having considerable notoriety, were able to negatively influence subsequent generations.

« One might optimize a stock portfolio with tax-exemption tools, but not the state of grace of an artist, the expression of a high-level athlete’s instant that plays out between perception, adaptation, and creativity. We can, however, speak of improving, optimizing preparation. But that is another moment, another reality, and another temporality. »

For people of my generation and the next, up to the two thousands, I know that in my sports family, everyone will understand well what I am alluding to here. Sometimes these behaviors had a dramatic outcome. The worst part is that, later, some of these individuals retrained as sports leaders, and this is particularly true in combat sports.

I suppose it’s related, but when I stopped competing and started teaching judo in clubs, then coaching young athletes toward the high level, I was driven by the idea of a project that could be titled: « Coaching Differently »!

I thought that the mistakes and abuses of coaches were primarily a consequence of a lack of pedagogical training and deficiencies in training methodology, particularly in the field of human sciences… In France, there was no ethical and deontological guide (and I think that’s still the case) like the tool that the Coaching Association of Canada has already published for several years.

In training for sports educators and coaches, starting from the late nineties, the transmission of characteristics of young athletes (children and adolescents), and the stages of their development, taking into account the effects of maturation, were neglected in favor of what are called performance optimization tools. The vocabulary used alone seems wrong to me and indicates a vision, an approach that is not mine.

One might optimize a stock portfolio with tax-exemption tools, but not the state of grace of an artist, the expression of a high-level athlete’s instant that plays out between perception, adaptation, and creativity. We can, however, speak of improving, optimizing preparation. But that is another moment, another reality, and another temporality.

So, it seems to me that we have « neglected »—and that word is weak if we refer to the testimonies we have received concerning SGBV—the ethical and deontological awareness and training of coaches. For example, in combat sports where the athlete/coach relationship (until very recently, we said « coach/trainee relationship ») was most often characterized by a power imbalance. We reproduced an archaic model for decades, which induced a minimal level of collaboration, and where an authoritarian relationship was the norm (« you do what I tell you to do »). Those who tried to do otherwise suffered the criticism of « listening too much to the athletes » followed by the injunction « you must be tough » – where a « we must be demanding » would probably have been enough. I speak about this knowingly because I lived through it.

In 1998, a study by the INSEP Sports Psychology Laboratory showed the clever strategies of female athletes in the French national judo teams to escape the coercive and violent climate they were subjected to. Since that time, my intuitions had led me to seek out the experts in this avant-garde laboratory.

1998 is also the year I stopped coaching at INSEP. I could no longer tolerate the atmosphere, the climate, the way the athletes were treated. I joined the training division at the Judo Federation to develop projects and educational tools (the Perfectionnement DVD and video collection and the national Projet Judo project in particular), which also allowed me to continue working with experts from the INSEP Sports Psychology Laboratory as part of my role as a research correspondent.

The lack of coach training at different times is not only reflected in an authoritarian, even coercive, coach/athlete relationship. It is almost always accompanied by a dysregulation of training loads through an incoherent increase in volume, in the quantity of the load to the detriment of quality.

« How can one think that under these circumstances athletes are in the right physical and mental condition to let go, take all the risks, fully use their faculties of perception and anticipation to adapt in the moment, intuit, be creative? »

When coaches are not sufficiently trained—and this still happens today—they may have a very approximate knowledge of training methodology, load management, and periodization, for example. When this is the case, they hide behind the platitudes and prejudices that have haunted all generations of judokas. And they overwhelm the athletes with volume, quantity, and sheer willpower. They push them to always do more, propose incoherent programs, become increasingly authoritarian, and, in the end, blame the athletes they were unable to properly prepare for D-Day, for « not fighting hard enough »! And that, for me, is truly mistreatment.

The debacle of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games is, in my opinion, partly explained by these (incomplete) elements of analysis, but the phenomenon has occurred at other times and will happen again.

For example, in the eighties and nineties, after inconsistent and failed preparation, athletes were punished. Double the training dose, double the volume upon returning from a major championship, even though the underperformance primarily stemmed from a lack of intensity and quality, and therefore a fault of the coaching staff in the design of the preparation.

At different times, athletes arrived tired and in « diesel mode » at most major events. They could no longer express speed or explosiveness. The coaching staff, stressed by the pressure for results and the stakes for the political sphere, the Federation’s governance, reassured themselves by giving in to the quantity of work and sheer willpower. By ricochet, the pressure on the athletes was tenfold.

How can one think that under these circumstances athletes are in the right physical and mental condition to let go, take all the risks, fully use their faculties of perception and anticipation to adapt in the moment, intuit, be creative? Those who succeeded in these critical moments are the ones who emancipated themselves from the doxa, the injunctions, the clichés, and other harmful mantras generated by the system itself.

That is why, when I became a coach for the French Junior teams, I immediately had a project to try and guide the training and coaching of young people according to different ideas and concepts. I felt an improvement until about 1996 or 1998. And then it went back the other way; our old demons had caught up with us.

« It’s complicated, and it takes courage to undertake this approach. You have to know how to step back a little, isolate yourself from what people think of you. »

The 1998 study cited above, to which European Judo Champion Alice Dubois contributed, was coordinated by the INSEP psychology laboratory. It could have been taken into account. But the Federation and the high-level coaching staff simply ignored it.

In the early two thousands, Philippe Fleurance, the director of the same laboratory sent a very disturbing letter to Alain Mouchel, the director of Olympic preparation who had his office at INSEP. The letter warned of risks of depression and even suicide in connection with what would today be called psychological harassment. But this alert, like so many others, remained unanswered by the sports bodies and the federations concerned.

Having gone through all these eras and experiences has led me to question the coaching and teaching professions, as well as their practices and the beliefs that often determine them… I have developed these themes in my last two books (Entraînement cognitif et analyse de l’activité, 4Trainer, 2021 ; Le revers de nos médailles, Dunod, 2023).

I believe that teaching, like coaching, is a global process. It is a human adventure that plays out thanks to encounters and is developed through the quality and relevance of interactions in multiple situations. It is a long process. It doesn’t happen in a single session, a single coaching moment, or a magical exercise.

I have often observed that coaches who have thought about this have changed their attitude, posture, and way of coaching. They are more aware of things and respect their athletes better.

But it’s complicated, and it takes courage to undertake this approach. You have to know how to step back a little, isolate yourself from what people think of you. Because the sport-business pushes all actors to do the exact opposite. You have to appear and constantly put on a show to satisfy the media sphere. It’s like politics.

In fact, everything happens as if a world, an environment, had been created where money and notoriety had become the cardinal values and had supplanted mastery, expertise, self-knowledge—in short, everything expressed by the high-level athlete, the judoka, when they are at their peak, in a state of grace, like an artist. In a way, we have inverted the values here. You’re going to give him three penalties and immediately post it on TikTok!

I am barely exaggerating, as one gets the impression that it is the media, broadcasting standards, advertisers, and financiers who determine most of the decisions and developments. One often gets the feeling of a trickery and imposture from those who are supposed to analyze, expertise, and arbitrate key situations. The leaders seek to satisfy the media first, because that is what their economic model imposes and what allows them to generate profit and visibility for themselves. We see where this drift is leading us with the evolution and absurd changes in refereeing rules. We heard a lot about it during the Paris Olympic Games.

My commitment to the fight against SGBV in sport through the Artémis Sport association thus extends my intuitions and experiences since the eighties, when I was an athlete myself. It calls for a systemic and global approach and response.

Respect for individuals, for the person, is the foundation of professional ethics and pedagogical reflection. We must start from there. Rebuild a set of benchmarks for all sports actors, and not just for coaches and sports educators—who are often the fuses or scapegoats of the system. Training and coaching practices, monitoring and management, group management, and professions related to sport will improve provided that the governance bodies do not themselves generate the ferments of an environment of violence, abuses, and dysfunctions. – All comments collected by Anthony Diao, Autumn 2025. Opening photo: ©Cabinet Véronique Guillotin/JudoAKD.

A French version of this article is available here.

More articles in English:

-

- JudoAKD#001 – Loïc Pietri – Pardon His French

- JudoAKD#002 – Emmanuelle Payet – This Island Within Herself

- JudoAKD#003 – Laure-Cathy Valente – Lyon, Third Generation

- JudoAKD#004 – Back to Celje

- JudoAKD#005 – Kevin Cao – Where Silences Have the Floor

- JudoAKD#006 – Frédéric Lecanu – Voice on Way

- JudoAKD#009 – Abderahmane Diao – Infinity of Destinies

- JudoAKD#008 – Annett Böhm – Life is Lives

- JudoAKD#010 – Paco Lozano – Eye of the Fighters

- JudoAKD#011 – Hans Van Essen – Mister JudoInside

- JudoAKD#021 – Benjamin Axus – Still Standing

- JudoAKD#022 – Romain Valadier-Picard – The Fire Next Time

- JudoAKD#023 – Andreea Chitu – She Remembers

- JudoAKD#024 – Malin Wilson – Come. See. Conquer.

- JudoAKD#025 – Antoine Valois-Fortier – The Constant Gardener

- JudoAKD#026 – Amandine Buchard – Status and Liberty

- JudoAKD#027 – Norbert Littkopf (1944-2024), by Annett Boehm

- JudoAKD#028 – Raffaele Toniolo – Bardonecchia, with Family

- JudoAKD#029 – Riner, Krpalek, Tasoev – More than Three Men

- JudoAKD#030 – Christa Deguchi and Kyle Reyes – A Thin Red and White Line

- JudoAKD#031 – Jimmy Pedro – United State of Mind

- JudoAKD#032 – Christophe Massina – Twenty Years Later

- JudoAKD#033 – Teddy Riner/Valentin Houinato – Two Dojos, Two Moods

- JudoAKD#034 – Anne-Fatoumata M’Baïro – Of Time and a Lifetime

- JudoAKD#035 – Nigel Donohue – « Your Time is Your Greatest Asset »

- JudoAKD#036 – Ahcène Goudjil – In the Beginning was Teaching

- JudoAKD#037 – Toma Nikiforov – The Kalashnikiforov Years

- JudoAKD#038 – Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard – The Rank of Big Sister

- JudoAKD#039 – Vitalie Gligor – « The Road Takes the One Who Walks »

- JudoAKD#040 – Joan-Benjamin Gaba and Inal Tasoev – Mindset Matters

- JudoAKD#041 – Pierre Neyra – About a Corner of France and Judo as It is Taught There

- JudoAKD#042 – Theódoros Tselídis – Between Greater Caucasus and Aegean Sea

- JudoAKD#043 – Kim Polling – This Girl Was on Fire

- JudoAKD#044 – Kevin Cao (II) – In the Footsteps of Adrien Thevenet

- JudoAKD#045 – Nigel Donohue (II) – About the Hajime-Matte Model

- JudoAKD#047 – Jigoro Kano Couldn’t Have Said It Better

- JudoAKD#048 – Lee Chang-soo/Chang Su Li (1967-2026), by Oon Yeoh

Also in English:

- JudoAKDReplay#001 – Pawel Nastula – The Leftover (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#002 – Gévrise Emane – Turn Lead into Bronze (2020)

- JudoAKDReplay#003 – Lukas Krpalek – The Best Years of a Life (2019)

- JudoAKDReplay#004 – How Did Ezio Become Gamba? (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#005 – What’s up… Dimitri Dragin? (2016)