The promise to approach judo “by words, beings and acts” on JudoAKD sometimes leads to joyful confluences. This is the case with the text below, reproduced with the kind permission of Rémi Guyot, its author.

Rémi is a passionate and fascinating man. Not a judoka but far more martial and disciplined than many practitioners encountered randomly on the tatami. We have known each other for nearly twenty-five years, through musical, textual and cinephile affinities confirmed many times over. He has sometimes hosted me on the eve of Parisian competitions, approached sometimes as a competitor, sometimes as a journalist. Constantly more astounding in his radicality, clarity and curiosity about his own existence and that of his contemporaries, Rémi is one of those people who prefer to take notes rather than give them.

Mind Fooled, the Substack he launched coming out of lockdown, is the continuation of this meticulous work of observing words, beings and acts – well, well – that populate his very rich inner life. There he records with the conciseness, sobriety and absolute sincerity that have always been his trademark his numerous obsessions, memories, readings and other intuitions, all stimulated by an existence of rare density, both personally and professionally.

The text below dates from November 23, 2025. Reading it made me say to myself that Jigoro Kano couldn’t have said it better – so be it. – JudoAKD#047.

A French version of this article is available here.

The Professor Who Knew Nothing, by Rémi Guyot (Mind Fooled)

Or how at 9 years old, in a church, I found answers to questions I would ask myself 30 years later.

To explain why I am so interested in learning methodologies, one must delve into one of the most significant experiences of my childhood.

Between the ages of 9 and 13, my extra-curricular activity was circus. Every Monday afternoon, I would arrive at the church (!) that served as our training venue; I would glance at the pile of stilts, juggling clubs, giant unicycles, very soft mats and very hard balance balls, I would choose what inspired me most, and I would try to do something with it.

Either I would imitate someone I had seen using the object, or I would invent something else. When I got tired of it, I would choose another one. And the hours would pass like that.

My teacher, meanwhile, would walk among the children, big and small. He would give advice to one, observe another and suggest an idea to a third. From time to time, to whoever wanted to listen, he would propose a game: “Who can do the most hula-hoop turns on 3-meter stilts?”.

Everyone progressed, at their own pace, in their own way, at their own desire.

For four years, I learned dozens of mini-skills. Sometimes without realizing that I was learning to do things that no one else around me knew how to do — starting with my teacher. Yes, because my circus teacher didn’t know how to juggle. Nor ride a unicycle. Nor balance on a ball. Nor walk on his hands. Nor anything else we had come to learn.

Despite this extensive incompetence, it was through contact with him that I learned to do all these things. Before knowing him, I didn’t know how to do them; afterwards, I did. During this time, he never knew, and yet taught me. Me, and hundreds of other children.

Of all these accumulated skills, this teacher dreamed of making a show. A show of such quality that it could be part of the program of the largest performing arts festival in the world, held every year in Edinburgh.

This dream became a plan, and this plan became my reality, during a few summers spent in Scotland performing strange stories on stage, before thousands of strangers. The adventure stopped there for me, while the troupe continued its momentum and began to tour the world, subsequently performing in New York, Rome, Beijing, Hamburg, Paris, Ljubljana, Maastricht and Adelaide.

At the time, with my child’s eyes, all this seemed to flow naturally. Decades later, this episode of my life seemed unreal to me, almost incomprehensible.

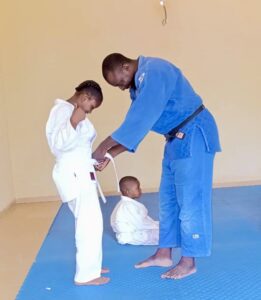

Intrigued by these memories, I recently reconnected with this teacher, Ian Scott Owens. From our very first exchange, Ian sent me a photo from our training sessions together.

I had never seen this photo, which must date from 1995. Upon discovering it, thousands of details came back to mind, increasing the desire to ask my adult questions to him and ‘Trea, his inseparable wife. They kindly agreed to answer them.

When I asked them how they had managed to accomplish such things, both smiled, then shared their vision of things. I discovered the behind-the-scenes of their pedagogy, which we had never discussed until then.

I could summarize their approach as follows:

- Give challenges. Learning didn’t follow a predefined academic path. However, numerous improvised challenges punctuated the progression, not as goals to achieve, but as mysteries to solve. And when the challenge seemed too great, the pedagogy mainly aimed to find how to break down the problem encountered into smaller steps.

- Encourage action first. The phrase I heard most during my four years of circus was “Don’t think about it, just do it”, and for good reason. Ian and ‘Trea’s approach was to encourage children to try first and think later. Confront the real difficulty, then think about how to face it — not the other way around.

- Give confidence by giving trust. “Never tell children that they are not capable of accomplishing something.” Deliberately, a great deal of freedom was given to children in their choices to pursue this or that activity. The space created was a giant sandbox, where all experimentation was allowed, with notably plenty of room for falls, in order to learn to get back up and try again. To my great surprise, circus, the discipline to which Ian and ‘Trea devoted their entire lives, was not that important in their eyes. “Circus wasn’t the goal. It was a tool, a weapon of massive construction. We simply wanted each child to find their way.” And indeed, upon finding the statutes of their circus school, I realized that it stated their mission was to “develop the physical and creative potential of children, using circus and art, to prepare them for the challenges of the modern world (…). The objective is to develop their self-confidence and give them a sense of belonging to a demanding and stimulating group.”

At the time, I was unaware of all this.

Today, observing how I educate my children, manage teams or develop the AI Discipline learning platform, I understand that this professor-who-knew-nothing ultimately taught me much more than a few circus tricks. And that I have a long way to go to reach the ankle of such sources of inspiration. – Original text reproduced with the kind permission of Rémi Guyot (Mind Fooled). Opening photo caption: “Ian on the left, Emma on the right, Ali on my shoulders” ©Archives Ian Scott Owens-Mind Fooled/JudoAKD.

A French version of this article is available here.

More articles in English:

-

- JudoAKD#001 – Loïc Pietri – Pardon His French

- JudoAKD#002 – Emmanuelle Payet – This Island Within Herself

- JudoAKD#003 – Laure-Cathy Valente – Lyon, Third Generation

- JudoAKD#004 – Back to Celje

- JudoAKD#005 – Kevin Cao – Where Silences Have the Floor

- JudoAKD#006 – Frédéric Lecanu – Voice on Way

- JudoAKD#008 – Annett Böhm – Life is Lives

- JudoAKD#009 – Abderahmane Diao – Infinity of Destinies

- JudoAKD#010 – Paco Lozano – Eye of the Fighters

- JudoAKD#011 – Hans Van Essen – Mister JudoInside

- JudoAKD#021 – Benjamin Axus – Still Standing

- JudoAKD#022 – Romain Valadier-Picard – The Fire Next Time

- JudoAKD#023 – Andreea Chitu – She Remembers

- JudoAKD#024 – Malin Wilson – Come. See. Conquer.

- JudoAKD#025 – Antoine Valois-Fortier – The Constant Gardener

- JudoAKD#026 – Amandine Buchard – Status and Liberty

- JudoAKD#027 – Norbert Littkopf (1944-2024), by Annett Boehm

- JudoAKD#028 – Raffaele Toniolo – Bardonecchia, with Family

- JudoAKD#029 – Riner, Krpalek, Tasoev – More than Three Men

- JudoAKD#030 – Christa Deguchi and Kyle Reyes – A Thin Red and White Line

- JudoAKD#031 – Jimmy Pedro – United State of Mind

- JudoAKD#032 – Christophe Massina – Twenty Years Later

- JudoAKD#033 – Teddy Riner/Valentin Houinato – Two Dojos, Two Moods

- JudoAKD#034 – Anne-Fatoumata M’Baïro – Of Time and a Lifetime

- JudoAKD#035 – Nigel Donohue – « Your Time is Your Greatest Asset »

- JudoAKD#036 – Ahcène Goudjil – In the Beginning was Teaching

- JudoAKD#037 – Toma Nikiforov – The Kalashnikiforov Years

- JudoAKD#038 – Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard – The Rank of Big Sister

- JudoAKD#039 – Vitalie Gligor – « The Road Takes the One Who Walks »

- JudoAKD#040 – Joan-Benjamin Gaba and Inal Tasoev – Mindset Matters

- JudoAKD#041 – Pierre Neyra – About a Corner of France and Judo as It Is Taught There

- JudoAKD#042 – Theódoros Tselídis – Between Greater Caucasus and Aegean Sea

- JudoAKD#043 – Kim Polling – This Girl Was on Fire

- JudoAKD#044 – Kevin Cao (II) – In the Footsteps of Adrien Thevenet

- JudoAKD#045 – Nigel Donohue (II) – About the Hajime-Matte Model

- JudoAKD#046 – A History of Violence(s)

- JudoAKD#048 – Lee Chang-soo/Chang Su Li (1967-2026), by Oon Yeoh

More Replays in English:

- JudoAKDReplay#001 – Pawel Nastula – The Leftover (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#002 – Gévrise Emane – Turn Lead into Bronze (2020)

- JudoAKDReplay#003 – Lukas Krpalek – The Best Years of a Life (2019)

- JudoAKDReplay#004 – How Did Ezio Become Gamba? (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#005 – What’s up… Dimitri Dragin? (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#006 – Travis Stevens – « People forget about medals, only fighters remain » (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#007 – Sit and Talk with Tina Trstenjak and Clarisse Agbégnénou (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#008 – A Summer with Marti Malloy (2014)

- JudoAKDReplay#009 – Hasta Luego María Celia Laborde (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#010 – What’s Up… Dex Elmont? (2017)

And also :

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#01 – Episode 1/13 – Summer 2025

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#02 – Episode 2/13 – Autumn 2025

JudoAKD – Instagram – X (Twitter).