Born on August 17, 1965 in Lyon 4th district (France), Pierre Neyra is blowing out both his sixty candles and celebrating his half-century license in this year 2025. Technical director of the Ain department for three decades, the Saint-Denis Dojo instructor has added another string to his fourth dan bow in recent years: numerous trips and training camps abroad. A breath of fresh air that is both familial and pedagogical, which now allows him to approach each new season with the calm of seasoned veterans. – JudoAKD#041.

A French version of this interview can be read here.

How did you get into judo, Pierre?

Listen, it’s the classic pattern: daily life, school bullying…

Really?

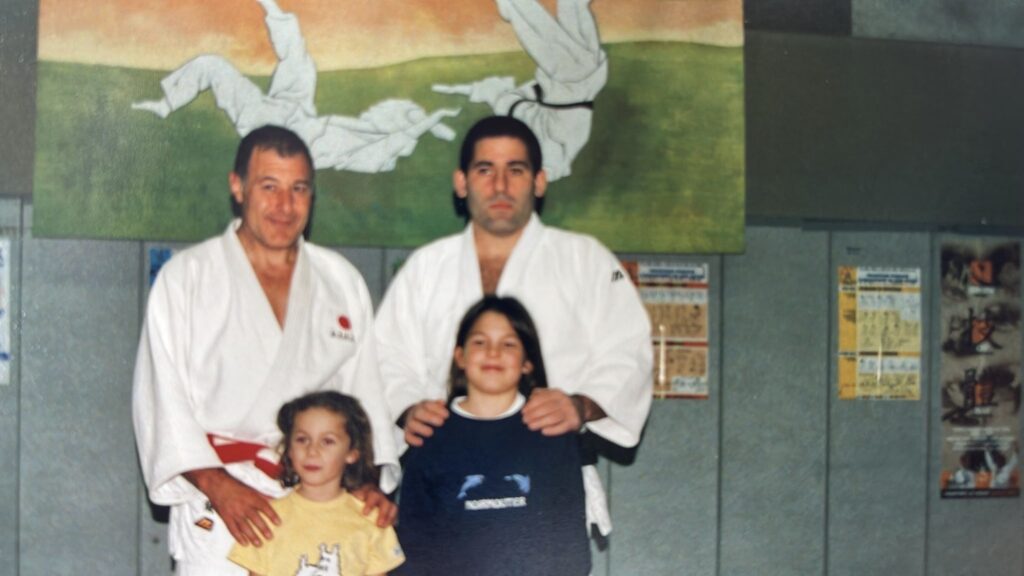

Oh yes. Because the build I have today, I didn’t have it when I was little. I had a minor illness and vitamins that made me develop into what you know me as… Everything is connected, actually. Around the age of nine, it was my mother who decided to sign me up at the Croix-Rousse dojo. At the time it was run by master Roger Bascobert, a world referee who had officiated at the Munich and Montreal Games. He was supposed to do the Los Angeles Games but he got cancer in 1984 and died a year later – may he rest in peace. He was a great man of Lyon judo. I was young but I had the chance to know him.

Was judo just a hobby for you at that time?

It was a hobby, yes. But I loved it and I was dedicated. It’s funny because my parents also wanted me to do music but the truth is that I memorized my judo scales better than my music theory scales. So very quickly the music lessons turned into judo lessons and then it built up crescendo. I got my yellow belt with Alain Aden, who has since taken on responsibilities in jujitsu and teaches at the Dojo d’Essling near Part-Dieu. After him there was Gérard Thinet and, when I left, it was the period when Pierrot Blanc arrived. It wasn’t because of him, you know. It was a logical evolution.

You left to go where?

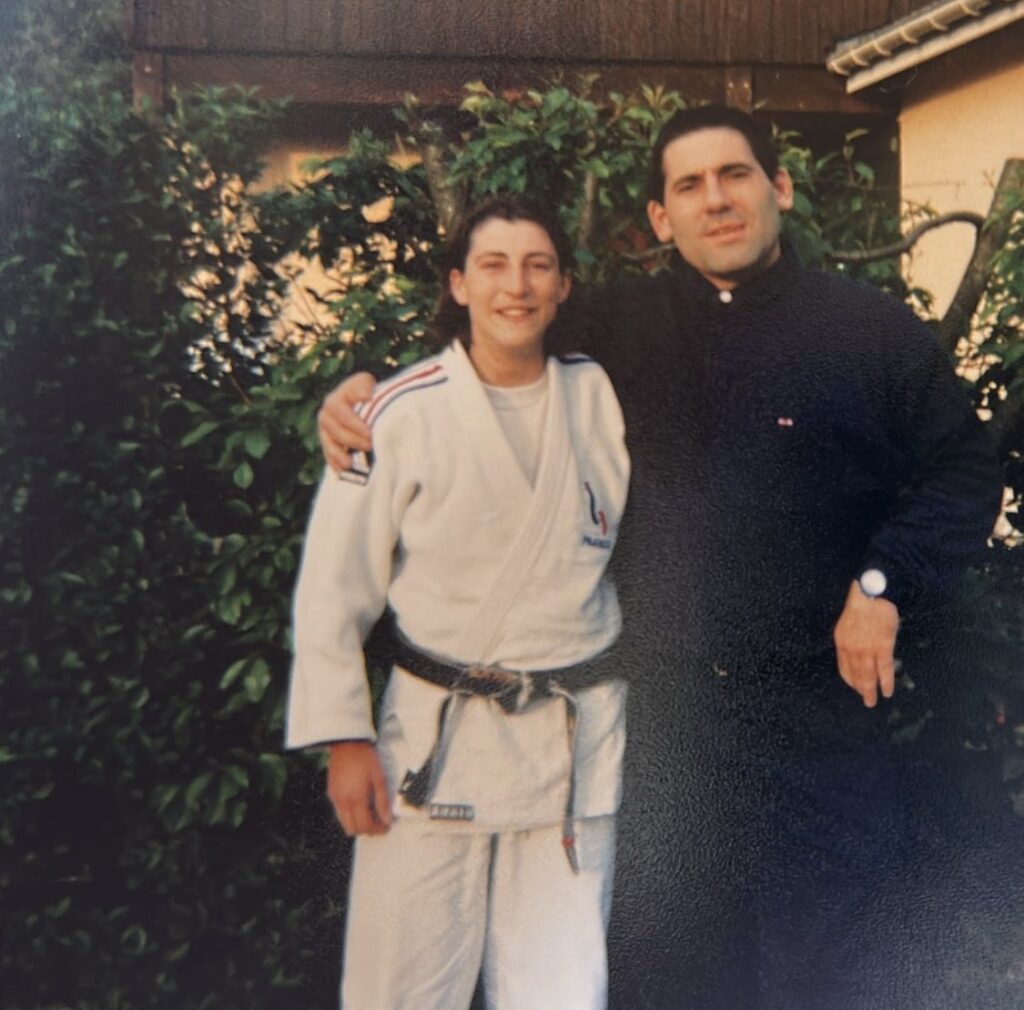

I continued at Fuji Yama in Rillieux-la-Pape, with the Muller brothers – Eric, as a coach and Thierry, who competed. It was only after that I landed in Ain, when I was doing military service, my diploma, all that.

Was it at that time that you considered making judo more than just a hobby?

Actually it all worked out well. I’m lucky to often arrive at the right moment. Already, at Croix-Rousse, Gérard Thinet had asked me to come help him on Wednesday afternoons. It’s something many people do – you did it too no doubt [Editor’s note: yes] -, even today, by asking a dedicated student to come lend a hand. On the side I was competing, I was throwing people and I loved it. I had the build for it, I have to say! Anyway, that’s how I got hooked.

Do you remember your first steps in teaching?

I have images, yes… I can see Bruno Mure in his green belt in front of me during the bow, just before he took off [now director of the France Training Center in Grenoble, Bruno Mure reached the national podium several times in the U66kg category, Editor’s note]. I’m also lucky to meet other instructors. Through Isabelle Mayoud for example, who now runs the Lyon Martial arts shop, I become friends with Jean-Jacques Sellès, a fellow judoka who had done some substitutions at the club. Then Jean-Jacques went to the city of Chassieu where he became head of the Sports department. As luck would have it, he then asked me to work in the municipality as an activity leader at leisure centers. I didn’t have a diploma, but well, I agreed to come help him. From there I really got to know him and his family. We became very close friends. One thing led to another, I also did substitutions at school to show a bit of judo. All that kept me busy.

Did you go through military service?

Yes I did Sports Army in Marseille, with Jean-Paul Coche, Richard Melillo… and Fred Buzon, who you know well! After that, they encouraged me to get my diploma, so I went to the Grenoble training center. I was on the State Certificate lists there, but not on the athletes’ lists – which didn’t stop us from training together with the Karim Slimanis, the Fabrice Guénets, etc.

Solid guys!

It was a very high level class, yes. In fact when I got my State Certificate, it was Karim Slimani who told me he had a friend looking for a teacher around Bourg-en-Bresse in the Ain department. It’s true that in Lyon, there weren’t many opportunities. That’s how I ended up in 1990 in Bourg-en-Bresse, where I still am today.

Did you move there?

No, I commuted. Actually I lived in Lyon until 1992. It was only after that I got an apartment in Bourg-en-Bresse. I have to say that during that period I also had to substitute for a while for Geff Valente at his club in Lyon’s third arrondissement, as well as at Dargent college for the equivalent of the departmental judo class that Jérôme Muller handles today. It was Patrick Nolin, the technical coordinator at the time, who had asked me if I was interested. That’s where I got to know Geff Valente and we became friends… You know, we always have a vision of people based on what we hear about them, but in the field it’s something else. Geff was quite a character and it was a joy to exchange with him… Once in Ain, Patrick Nolin asked me to do some group training missions. Then when Arnaud Perrier came back to the region, he integrated me into the technical team of the League of Lyonnais that he set up. It then included the departments of Ain, Loire and Rhône.

At what point, when you took on federal functions, did you impose your style, your touch?

That’s a real challenge to take on. The challenge of doing things. After that, it’s the work, the evolution, the passion of always discovering more that makes you invest enormously. So since 1992 when I took on my functions, it was only in 2003 that I officially became a federal technical coordinator. So that’s eleven years spent between volunteering and some payments here and there. All that builds a perspective, a sensitivity toward people. It definitely counts when you come to propose actions.

This side of taking lots of kids places, of taking initiatives that aren’t necessarily done everywhere, how did that come about?

It came from meeting people. Let me give you an example: every judoka dreams of going to Japan one day. For vacations, everyone wants to travel here and there – but many put up barriers, mainly financial ones. Japan, for me, happened in 2004 with Patrice Palhec, who was already starting to do well over there. I asked him if I could go with him. We went in February as a group of four, with a student, his son and him. I enjoyed that first stay so much that I quickly wanted to launch the next one… For the other trips, it’s a desire that my wife and I share. The opening of the Schengen Area changed everything. One day, we were in England and I said to her: why don’t we visit all the capitals of Europe? It started like that. Today we’re at twenty or twenty-five capitals.

Do you do that in the summer?

In summer yes. And with a judo approach. There’s always the little angel and the little devil: there’s the angel for vacations and the devil that tells you there’s judo. There’s always a Post-it lying around with an email address or the website of a local club. It’s funny because we’re on vacation and then I don’t know, it’s like honey, it attracts me… The Internet has really multiplied the possibilities. I’ve sent I don’t know how many emails all over the world – I’m talking about Australia as much as Canada, you know. I often got responses and that’s how the alliance with Slovakia was created, for example, or exchanges with Brazil and North America. It’s also all that which led to creating the tournament at the club level.

When did the first Open de Bresse start, by the way?

We launched it in February 2008 and we stopped it this year because we couldn’t do more. It lasted sixteen years. I had created the Saint-Denis-les-Bourg club in 2003 after an experience in Bourg-en-Bresse that had ended with difficulty. Fortunately, the desire was still there. I created the club and there was a dynamic, a demand. The athletes followed me and today, after twenty-two years, the club is viable and functional.

In your tournament, there were also foreigners who came, the Italians notably.

I don’t have it in front of me but we had an incredible list of foreigners. If we look outside Europe, in the early days we had Martinique – you’ll tell me, Martinique is France, but for us it was something. Why come to us in Saint-Denis? Martiniquais who come to Paris for a tournament, that’s logical. But coming all the way to Saint-Denis-lès-Bourg? They came two years in a row, we got to know them… At that time we had the Swiss women’s national team who had come as neighbors, they were the first foreigners who kind of got the working group’s foot in the door. After that it took off: we had the English, the Spanish, Saint-Pierre-and-Miquelon (which is still French territory)… In all these contacts there was a big exchange that happened with a teacher from Slovakia who helped me develop many things. They travel by bus and have this facility to gather together. Even if there are sometimes local rivalries between them, it’s all collaborative work. In the bus, you have the Czechs, the Poles, the Ukrainians, the Hungarians. After that, other friends joined in. There was Austria, Germany too, Denmark… and even up to the national B team of Canada.

What age groups was the tournament for?

It was for minimes and cadets. At the beginning it was open to juniors. Today it goes back a bit, but there was a period of shortage. Proposing a junior tournament, having foreigners come and only offering them one or two fights, that wasn’t great. So we added seniors, and the juniors fought with them.

And the Italians came?

Yes, they gave us that pleasure. We also had Serbs. Those were families who moved around a lot too so it allowed me to make connections.

When you go away in the summer, do you take students with you?

No, not in summer. I’ve developed a taste for going to see people at their homes, mixing judo and family vacations for about ten years now, but without students. Basically, I go away for about ten days on family vacation and, for more than ten years, I take advantage of it to do a training camp in Slovakia or Poland. Or both, because they also group together, because it’s getting complicated everywhere, we shouldn’t deny that either. France isn’t doing well but elsewhere in Europe it’s not so simple either.

Are you the one who leads these training camps?

Yes. I watch, I learn, I exchange. Last year, there was a huge experience. They brought in a team of thirty Ukrainians from Kiev. I lived through an exceptional experience. These kids arrived, they looked sad – and I can’t work with sad children. And then these are my vacations, I’m there to enjoy myself, I don’t want to have tears in my eyes every five minutes. The coaches were two young people, a rigorous team. I managed with judo to relax them a bit, to change the mindset. These are vacations, yes, but with work, another approach, another pedagogy that doesn’t prevent the whole thing from remaining quite rigorous. On the second day, I saw the kids smile. Today these are exchanges on Insta, on Facebook. It’s nice.

Your wife Catherine, is she a judoka?

Not at all. Forget about sports [Laughs]. For her, these are her little vacations. While I’m at judo, she settles down at the pool or the local spa. After judo, she joins me for those convivial moments, of laughter and sharing. It allows us to clear our minds. These are things that are getting lost a bit, in France.

Do you feel that?

Yes, very strongly. Sometimes when returning, it’s like a weight that comes down. Everyone who goes on vacation here and there says it: as soon as you find French territory again, you have this gloomy feeling. All that is a bit sad because me, at this time of year, I aspire to exchange about lighter things.

As a Frenchman and judoka, do you feel like you carry a virtual bib or even a status when you teach abroad?

Yes, especially since every year they make me a T-shirt with my name on it, and it goes all over Slovakia, Poland, Ukraine… I don’t have any pretensions about it. I know there are other people who have higher value than me, but there you go, a friendship has been created.

What do you have the students work on during your training camps?

It’s mainly a certain pedagogy that we French have internalized as a base. They, on the other hand, have stayed more on Jigoro Kano’s Gokyo. The first year, when I do the training camp with children, it’s very playful and it makes judo. And then they ask me: « Do you want to examine katas? » When I saw the kata examinations, I cried.

How so?

First grade passage, first dan of a couple. No unbalancing, no gripping. The three movement times don’t exist. I’m on the jury, I have tears in my eyes. They tell me « what’s wrong with you? » Babbling, I say but what’s happening? What is this? They tell me it’s normal. That they learn kata from a book and they try to catch videos here and there.

How do you react?

I said to myself: I have to give them some tools. I sent them videos of what we do in France with certain educational pedagogies… After that, we mustn’t forget that over there there are forty clubs. To give you an idea, the Ain department, we’re at about five thousand licenses, that’s Poland and Slovakia combined, you know.

What’s the difference in teaching level?

In Slovakia for example, since I have more experience with that, there are no professional teachers, it doesn’t exist. There’s just one in Banská-Bystrica but it’s a military club, and there the instructor is paid because of that status. The other clubs, it’s all volunteer work, so there’s a whole pedagogy to build… For a high-level seminar for cadets, I do a lot of preparation work with a young person who is at the Slovak Federation. When I see the instructors arrive, I see yellow, green, blue belts. In total there are about twenty in front of me and, out of the twenty, I have two black belts. For us, a teachers’ seminar with only two black belts is unthinkable. There, it’s different. It’s the desire to transmit that takes priority. Basically I have my blue belt, I love judo, so I teach it.

I imagine you have your share of anecdotes…

I lived through a quite surprising experience during a grade examination, yes. My friend Villiam Kohút, who is sixth dan, asks me if I want to judge with them. I sit in the chair next to them, but only as an outsider. Because giving my opinion remains complicated with the language barrier. There, a couple arrives, a man and a woman. The woman is quite strong. They put on the judogis, they go up on the mat and I see that the woman is a white belt. The man, brown belt. The first technique, uki otoshi, he plants her on her head. There, once again, the tears come out. I say to myself: it’s not possible, what’s happening? I have a friend who is the translator, she taps me on the shoulder, she says: we continue, watch. Kata guruma, he explodes her. He gets up, she takes two hours to get up. It continues, and over there, when you’re a brown belt, there are the five series. I thought he was going to kill her. And there my translator friend tells me: « It’s his wife. She doesn’t do judo. She put on the belt and the judogi just today, so that her husband could take his black belt test, because there’s nobody in his club to take it with him. » I said, but it’s not possible. The first thing I do is go see the woman to congratulate her. I tell her: « It’s you, Madam, who is black belt, not Mister. It’s you. » They gave the black belt to her husband. Me, I would have said no. But it’s not for me to say… Back in France, I tell myself that we have to try to move forward a bit. I even contact Guy Delvingt to come try to bring some elements so they can work. Today, I can say that it’s on the right track since there’s a Slovak junior couple who are European kata champions!

You mentioned the weight that you find in France each time you return from abroad. Do you think many people would benefit from living experiences like these to better appreciate the richness of the judo heritage we have in France?

Absolutely. In fact I observe that there are more and more clubs that are taking the plunge today. Maybe not in this way though. Many go do a little training camp abroad or a little exchange. I remember, there was Alain L’Herbette who was one of the pioneers of that in the region. Some go to Germany, Poland, Switzerland or Italy. It’s starting to become democratized, especially since summer training camps in France are starting to melt away like snow in the sun. Usually, we received the judo magazine, and then, you got to May, you saw two pages of training camps, you chose. Today, national training camps are being supplanted by international gatherings in Valencia, in Italy, etc.

Speaking of Italy, we often cross paths at Christmas at the Bardonecchia training camp. How long have you been going there?

The first time on the mat with my students was the 2013 edition, the one with Olympic champions Urska Zolnir and Ole Bischof. And after that, it took off, going from club to departmental level. Since then I went for about ten years but it’s been two editions now that I don’t go anymore.

Yes, by the way, why don’t you go anymore?

I don’t go anymore for different reasons. Age? Not really, because I continue to go abroad. Actually it’s mainly the increase in French people that strikes me. Since the 2022 edition with Canadian Christa Deguchi and Japanese Soichi Hashimoto, this training camp has taken on enormous scope. It’s very good in itself because it remains an excellent training camp. But there are many French people today and then the level has also shifted from a very good level training camp to really excellence. Because now the French team is there, PSG is there, that’s no small thing. And that’s where we start to have randori refusals.

I imagine that on top of that you’re asked to go elsewhere…

Yes, I’ve been invited here and there for years. With time and travel I’ve created a network and this network has become friends who even help me with my vacations. It’s a cliché what I’m going to tell you but every time you go to a country, if you’re lucky enough to find someone who can guide you to discover things other than the average tourist, it’s always richer. There I have opportunities in Slovakia, in Albania… Just after New Year’s Day, there’s an international training camp in Croatia. I went there with my students and it’s pure joy. I found the Italian level, but with much fewer French people this time. There were some randori refusals but overall my students really had a blast. There was the little Croatian Katarina Kristo, who came close to the podium at the Games, as well as two heavyweights who were in Paris too, a Belarusian and a Slovene who fought for Greece, I think. There was very good level, I loved it. After that I’m also invited to Berlin, where I have a French friend. There’s a big training camp at the same time as Bardonecchia. There too I want to do it, but well there it’s the cost because Berlin is another distance. It’s a capital, so the hotels, etc.

The federal calendar is saturated in France. To be able to organize these trips abroad, you have to take from your own time. What’s the ideal rhythm for you to feel good and to last in this profession?

Listen, I’ve adapted to the modern world. That means I’m on almost all the networks at the club level. Today I do almost more computer work than mat work. After that, what sustains us is passion. You can’t take it away, it’s our Obelix magic potion, passion. I’m a bit in the same work pattern as a Patrice Palhec. It’s the passion to transmit, the passion to still discover, to go see, to travel and make others travel, to make children dream. With age you try to ease up a bit but the passionate person, he doesn’t count his hours, he doesn’t look at his end of month salary and he’s on the roads bringing children here and there to make them discover and if possible make them love this discipline. The exchange is both sporting and cultural. The professional is the one who opens the dojo at five p.m., who closes it at nine p.m., without asking questions. And then who logs his hours.

How do you see the evolution of instructors today?

The reality on the ground is that the instructors who are at the edge of the mats to coach are getting grayer and grayer. After that it’s also that we’ve lowered the standards for diplomas, so people get smaller diplomas. Sometimes it’s just to say: I have a job and I do this on the side. Me, I’m one hundred percent for judo. Look at Alain Chambefort, who you know well, he taught physical education all his life on the side but look at everything he did with his kids: ski camps, sailing, etc. People don’t realize.

I was at the fifty years of the Chasselay club, in 2022, in the presence of Loïc Pietri. André Ramousse’s (1937-2021) daughter paid a touching tribute to her dad. From memory she told how when he came home from work at five p.m., he had his ritual: he made his little sandwiches, washed his feet and then he took his judogi and went to teach at the club, where he started a second workday.

Yes, people like that, it’s the DNA of our discipline.

These trips abroad, what do they bring you, humanly?

It regenerates. The fact that my wife doesn’t like flying forces us to take our time. There’s a lake, a gathering, you stop. You hear music, you stumble upon a beer festival in Germany, you say, wow that’s great. Last year we passed through the Hungarian and Slovak border, in the Tokay vineyard area. I wanted to treat myself since it was my birthday period. I’ve been passing by for twenty years to go to the tournament, I had never taken the time to stop, and there you have a local festival and you discover a whole bunch of private cellars. That was a beautiful moment.

We crossed paths once at a World championship in Budapest. You were returning from your European tour and you had stayed for the championship.

Yes we were returning, and we made a little stop in Budapest. We liked it too because it’s a very beautiful city.

The East is your thing apparently?

Today, everything happens in the East. You have Croatia which has become unmissable, Hungary which hosted the World championships in 2017, 2021 and 2025… These are countries that remain inexpensive and, as for Budapest, you have the competition hall and you have the main hotel that adjoins the hall. It’s very well organized.

Do you remember your first trip abroad?

My first trip abroad was to the Czech Republic. We arrived, we settled in a tourist agency to see where to stay. I hadn’t taken any guidebooks to read, we really did everything on the spot. And we arrived in a little run-down street with an inn. They had a bar downstairs and upstairs, there were a few rooms. The cars in the street were old Trabants. In short, the whole city was in its original state… Five years later, we wanted to go back but everything had changed, the cars were state-of-the-art, etc. They knew how to develop because they were very quick on the Internet system to make themselves known. And then joining the European Union did them good.

Regarding teenagers, I hear two different perspectives today. On one side in Eastern countries or rather in the Caucasus, you have kids who are super agile and committed, while in Western Europe, it’s a bit more sluggish. Where do you place French teenagers today when it comes to taking them on the question of perseverance?

Good question. Since you’re talking about the Caucasus, I was lucky to meet a team that had come to the tournament. I had organized a one-day training camp the day after the tournament, and that’s where I got to know them. I saw wonderful kids, with unique agility and commitment. It’s actually a debate I have today with the father of one of my students. He’s Chechen, his son competes in poussins, and he wants him to be champion. He makes him work until 8:30 p.m. in the evening. That strikes me because for me, training a champion, that’s not it. For me, championitis right away, it’s too early. We at that age seek progression. Yes it’s good that he’s champion, but poussin champion, what’s that? On the other hand in the East, culturally, the poussin champion is a champion. It’s not the same culture or the same expectations. Under certain latitudes, champion is right away. The problem is that after that you need a national team behind. You have to train young people who want it and who stay the course to the end. We have made the choice not to put championitis forward. We favor an integrated progression, step by step… Now, today you know it very well, there’s probably a happy medium between cocooning our children and the club blow if you didn’t put the right foot forward or if you didn’t raise your head, since that’s how it works under other latitudes. The « make it or break it », for me, you don’t have the right to allow yourself that. There’s another way to work.

Where do you place the cursor in France today?

I’ll give you an example. A few weeks ago, we had the Ain championships. Sunday morning, there were the seniors. It was classic, simple, basic. In the afternoon there were the benjamin championships. Well believe it or not, I thought it was the World championships. I even got angry at a coach you know well and who will recognize himself. He wouldn’t stop, even between fights! The cursor, you see, it’s earlier in Eastern countries because it’s another culture. We, the international level starts from cadet. I think the cursor is there. That’s where there’s the switch between recreational practice and high level. In any case that’s where there are the first bifurcations… Now, in reality, many give up very quickly because there’s no collective framework of a national team behind. So OK, today, we see a beautiful Azerbaijan team, a beautiful Georgia team, but all that remains a complex sum of factors. What I notice is that in France, we managed to find the tempo to try to restore the prestige we had lost in certain categories.

How do you see French performances at the Paris Olympics?

When you see the results, you can tell yourself that being the host country helps. But you still had to beat the athletes on the other side! It’s case by case, and what they did is exceptional. And that contributes to this prestige that we feel as soon as we go abroad, even at our modest level. It’s one of the conversation topics that comes up most often after a good beer or a good vodka shot. It’s like when we go to Japan: if you’re French, the first randoris are hard. And when they realize we’re not the French team, that we’re just French people who come to exchange, the randori changes completely. We go from shiai to randori. That’s where you can start to express yourself.

How many times have you been to Japan in total?

Five times. Last year at Easter, I took a group of five coaches with me. They had never been there. All that is pure happiness. It’s pure pleasure.

This mentality of very (too) young champion that you mentioned, do you observe it often?

Very often when I go to these countries, it’s right away: « Champions, they’re there to win. » You have to see how they push their kids, whether it’s the coach or the parents. Over there, there’s a fervor. With us, we’re less in training than in teaching, with the idea of trying to put intelligence into it. I don’t want to say there are no instructors who are all in for making champions from poussins. It’s very much linked to the sociological parameters around the club. You have localities, the children want more than elsewhere, because they’ve understood that judo might be what allows them to get out of their neighborhood, their misery. For me, what makes the richness of an instructor is that: taking an ordinary child and making an extraordinary adult out of him.

The challenge today is also to manage to keep children beyond adolescence…

It’s a real issue: past a certain age, it becomes a desert. It’s not that before they left at thirty, but I have the impression that it’s getting younger still. Today in Ain, we have two big clubs: the Dojo Gessien that you know well, and Bresse Saône Judo. At Saint-Denis, we are the only club to have seniors both in recreational and in competitors. Apart from veterans, there’s nobody left in competition at Dojo Gessien. Yet there are people at training. Bresse Saône either, they don’t have any. There’s a generation of girls who participate, but in boys, there are one or two kids. Me, I lined up nine seniors this season at the Ain championships. I feel a bit like the last of the Mohicans, it’s true. And that’s what I try to tell my students: we’re here, we exist. We exist, even if we remain a small club with our two hundred thirty to two hundred forty license holders, compared to the six hundred of Bresse Saône Judo and the six hundred of Dojo Gessien. In proportion to our presence in senior, however, we’re in the big clubs. That’s where it’s a richness. And if on top of that your students get noticed for their attitude, their behavior and their commitment, I think you’re on the right track.

On the question of career duration, what do you observe?

There are stages. I think it was the Korean Jeon that you had interviewed who says he was lucky in his career not to chase after girls and to never have been injured. In the important stages, it’s true that adolescence plays enormously. But it’s true in all countries. In Slovakia, I have the experience of a super young girl: she came to the Open de Bresse in minimes, she crushed everything, with magnificent judo. I think she even won the Slovak championships… Today, it’s over. And she’s only twenty… Take also the case of Martina Hingis in tennis: yes, she was world #1 very young, but what is she now? What is she? It was strong very fast, but there was no progression stage. So yes these girls they reached the very high level, they succeeded, in a certain way. But over time it didn’t hold. And that questions me.

How do you see this approach of intensive training from the youngest age?

That’s the whole discussion I have with this student’s father. Today, he’s on a Japanese uchi-mata, but he’s only poussin. It’s too early. The dose of repetitions you have to inflict on yourself to achieve this mastery, it’s from cadets normally – and even then. Because uchi-komi is one of the work methods we have for everyone at any age, and it’s progressive. If you start doing series of two hundred uchi-komis with mini-poussins, I think at the end of the year you can say you’re closing shop. In France, Japanese culture, Eastern countries culture, that can be a source of inspiration, but it’s not our true culture.

An active champion like Czech Lukáš Krpálek is on that line too. When I went to visit his academy in Prague in early 2024 for L’Équipe magazine, a mom there explained to me that he favored educational activities over competition. It was only after fourteen that children made the decision to commit more or not.

Yes and these are kids who have good technical level, I’ve seen them work… He’s very healthy in his approach to things, this guy. I sense a person who’s really very approachable, very pleasant and sensible. In spirit, his vision of judo goes in the same direction as mine.

Precisely, with this distanced perspective you have on things, where do you see French judo today?

The breakup of the USSR remains an important factor of recent decades, since it means there are many more countries involved. But behind that, as I was telling you, we haven’t put this « championitis » forward. We favor an order of progression. That’s what explains that we maintain year after year a very beautiful French team from junior-senior level.

And at the societal level?

Today we can’t organize competitions anymore because gyms cost money, so it’s monetized. Look, when you give a medal to a child, when he comes down from the podium he takes it off his neck. Twenty years ago, the child came down from the podium, he kept it, he wanted to show it to everyone, he was going to spend his day with it…

My son literally spent a week at school with his gold medal around his neck when he was in first grade!

There you go. I remember a child who came to tell me: « I’m going to take my medal to my mom’s grave. » Who does that today? On the other hand if you put an iPhone around their neck, there you’ve won! The medals haven’t changed but the generation has changed. So there we are, now we’ve become « marketified, » so there’s the Pro League, soon there’s the Riner Cup… I’m not throwing stones at them! There’s money, these are athletes who train every day, at some point they need to have something. But it’s not my basic culture.

On the Paris-province relationship, do you find it works well or are there areas for improvement today?

There’s still work to do. Careful, I’m going to speak as an « old guy »: a shift happened with the creation of the Judo Pro League. Is it positive for French judo? Let’s say I wasn’t educated with money. Bringing in money, good or not good, I don’t know how to do it. I prefer to withdraw from those debates. If I had to summarise, I would say that Paris lives for money, and we live for the medal. That’s my feeling because it’s today’s society that’s like that. Everything is monetized, money is priority over the rest. I feel that Paris is that life and that we, behind, aren’t there yet. We try to temper all these things, because it’s complicated. Our reality is that in the countryside, we can’t manage to attract people. We have judokas, we have valuable kids, but we can’t make it because the money isn’t there. Even if it’s the same country, we don’t have the same lifestyle. And you have the size of our league too, which is a bit discouraging.

Meaning?

With us that’s the main problem. It’s cultural. Auvergne won’t mix with Rhône-Alpes, just as Franche-Comté doesn’t mix with Burgundy – I can tell you about that, because these are two territories I know very well. They won’t mix. And I think the Grand-Est league, the graft can’t take either. These are cultural aspects.

Add to that the parameter of distances and journeys…

When I competed, it was the time when there wasn’t yet the metro on those axes in Lyon. I took my bus ticket to go from my parents’ place to the Lyon Sports Palace for my championships. I was lucky because from Croix-Rousse to Gerland, it was the same bus. So my parents put me on the bus, off you go, I got off at the terminus, I walked a small kilometer and I arrived at the Gerland Sports Palace, because there was no Maison du judo at the time. It came in 1983 I think. Before it was the Gerland Sports Palace that served for championships.

Yes Thierry Frémaux told at length about those years in his essay Judoka… Does this distance factor contribute to families getting discouraged?

Of course, and more and more. People have changed their approach to judo. Sport is a leisure activity, but for many the real leisure today is to escape to the countryside on weekends and go do sports, play ball with their children, go cycling, go climbing, walk in the mountains, go skiing… Judo isn’t part of the fun sports to have a blast on weekends. Between driving three hours to go put your feet in the sea on the weekend at the beach, or driving three hours to see your son or daughter lose after ten seconds, the expense and energy aren’t the same.

Transportation time is also a real issue.

It’s a real issue, yes. And there we fall into a system that scares me a bit. You see the Region set up minibuses for clubs. You see those white and blue minibuses circulating everywhere? I have one at the club. On paper it’s great to want to free up parents. But I have the impression that in the process we’re losing them, the parents…

Yep I see that too in soccer with my son…

Completely. Besides, there are almost no more village soccer clubs. It’s all alliances. Because there are no more volunteers or no more supervisors for each age group. So they group together to be able to make teams.

Especially since these are ages where adult presence has its importance, if only to remind kids that there’s social life outside of earphones and cell phones…

There are lots of things at play there. We take them, that way we have our children, we organize ourselves, we also save money, it’s called carpooling. So it’s still a financial problem. But we lose the parents, we lose this contact, we lose these things. Parents today, we communicate with them by text. Direct contact, we’re losing it. Especially since by text, you sometimes have to read between the lines. With a risk of not always understanding each other.

You had told me about a Europe project you were working on…

I created something I call My own software. It covers everything useful to know about European tournaments, about exchanges. I did that during covid. The idea is to share my experience and this file is a slideshow built with my BE1 teacher at the time, with training center managers and instructors. Even Christophe Brunet for high level told me: « Your thing, it’s a treasure. » So I presented the possibilities: going to such tournament, seeing the style of opposition, knowing if there’s a training camp after it, if it’s a tournament-camp or only a camp. I had fun setting that up.

How does it work?

All countries are accessible via the slideshow. For example: Albania, I went there, so I can talk about it: training camp, fifty-person dormitory, cost calculated each year, interest of exchanges with Kosovo. In Austria, in Zelveig, you can go by car, accommodate fifteen people, affordable cost, brown belt level, and thanks to that the Dijon training center was able to participate. I hadn’t yet listed Slovakia, but it’s done now. Poland has also evolved a lot. And Ukraine is also a possibility. The goal is for it to serve others. I’m a bit in the spirit of Jigoro Kano: not keeping for yourself but transmitting. The Poland–France, Slovakia–France, Czech Republic–France exchanges must continue, it’s important in sport. They told me: « If it comes from you, it’s because you created this relationship. » So if I send trusted people, it’s accepted. It’s a bit like with the Japanese: you don’t invite someone you don’t know, but if it’s recommended, it’s simple. I was helped by instructors, training center managers, Christophe Brunet and others. The concept is nice, plus I translated it into English, so it circulates in several countries. It allows sharing these experiences.

You’ve developed tools to help others organize themselves?

Yes, look: the other time I took a colleague from Jura. She fell in love with the trip so I told her « You’re thirty so still have a future so go for it and I’ll help you… » All those who are students and don’t have money, you’ll see, you won’t regret it after. Today, everyone thanks me for doing that.

Your multiple connections also help you offer attractive rates?

That’s the goal. Because today kids almost don’t travel anymore with school. If the associative world can bring them that, so much the better. Then after it’s not the same cost and the money barrier unfortunately remains a reality. For my part I’m lucky to have created a network, and this network allows dividing the cost by two, and that’s an invaluable treasure, because when we go there, we’re invited because there’s a relationship that was created over time.

Is it more complicated to organize in France?

You can’t imagine the cost. That’s also a barrier, but it’s incredible. Until now it still worked. I accommodated, I did school accommodations, because it’s big groups. Hotel is complicated in Bourg-en-Bresse, but school accommodations, that worked. Today we’ve put a law, you need a sworn responsible guard for everything security-related, it costs you five hundred euros a night for a person who sleeps – who sleeps, on top of it, because if there’s no alarm, he sleeps! Since they came three days, you have fifteen hundred euros to pay. When you don’t have subsidies anymore, how do you do it? Well I tell foreigners « Stay home. »

Ronaldo Veitía’s Cubans were accustomed to this makeshift system in France. We had actually brought them in 2015 to Dojo Gessien.

Yes there are still countries like that. I think if we don’t see Cubans anymore today it’s because of this financial system that has weighed down our discipline – and not just ours by the way. Yet there are always valuable young people there, we still see two or three come out… Well they don’t have behind them the aura of a Ronaldo. He himself said it, by the way, at the end of his career, that Cubans are eliminated not on the judo criterion but on the money criterion. Money has put a brake on those countries.

By the way just before the Paris Games I went to interview Idalys Ortiz for Libération. The atmosphere was twilight-like. Since many athletes had left in previous years, everyone was watching everyone.

Yes and all that creates tension and you’re surprised after that athletes don’t perform on D-day, you know. When they’re under stress like that, if everyone is watching each other… I experienced that with the Israeli team. When there was the Lyon International Junior Tournament, I found myself responsible for managing the competition area and when you see the Israeli team arrive, wow, you have the bodyguard with the holster in his pocket and everything. That adds stress to the fight…

Summer is ending as we resume this interview. You returned yesterday from Slovakia. How long does it take you to drive back?

It’s eighteen hundred kilometers. I’m the only one who drives, Madame doesn’t like driving much, so I’m the one who has to do it. For these vacations, that’s four thousand kilometers total.

This country seems to have become your second home, over the summers. What do you do there now?

I participate in training camps and their tournaments. I did a seminar this year for cadets in Piešťany, which is north of Bratislava, with a group of Hungarians present. It’s the Federation’s historic club. They sometimes send athletes to Japan. I also took part in an instructors’ seminar in Žilina. I also sometimes go to Bardejov or Michalovce, at the eastern end, even to Poland. Regarding the audience, there were seventy this year, including about twenty athletes from surrounding clubs. It ranged from little ones – there were some who were six or seven years old I think – but then I had juniors, even veterans preparing for World championships.

Are there gatherings with their Czech neighbors?

Not much more. They keep contacts. When they do their tournament, the Czechs are always there, but Michalovce and all that sector I know well, it’s on the opposite side. Žilina, Trenčín, Piešťany, Bratislava, that borders Austria and Czech Republic, so the contacts are maybe different.

On the idea of bridging between last season and the one coming, what assessment do you draw personally from the past season in terms of your responsibilities?

The season that passed was very complicated for me. I find it complicated because we’re at a turning point. It’s a new olympiad and I think the Federation has stepped up, particularly on computer objectives. And that’s a turn that’s sometimes complicated to take for some.

Do you feel it at your level?

And how. They installed systems and people are lost. In my mission, I try to do my work as best as possible, but it’s complicated. I’ve evolved in computers, but sometimes there are things that are beyond me.

Do you think we’re losing people in clubs because of this evolution?

I think so, yes. Among the old-timers especially. Young people don’t take over, they get the diploma but don’t teach or, if they teach, it’s just for the course fee. Now it’s more dispassionate, it’s professional: « I come, I get my salary and I leave. » There’s no longer this conviviality of the past. It has changed, for sure, but it’s difficult, and all the old-timers really have trouble hanging on. I think of someone like Alain Chambefort, who has given so much for his students for decades. I can tell you it’s starting to get hard. He continues because he loves it but it’s becoming really very hard. We often talk about it together.

At one time, when a teacher left a club, he placed an ad and the position was filled within the week. Today it can be several months before he’s replaced. How do you see this evolution over the years?

As I was telling you earlier, there are two types of instructors: the passionate one and the professional one. The professional, you tell him his class is from five to six p.m., he does five to six p.m., no more. And he waits for his salary at the end of the month. The passionate one, he arrives half an hour early, he stays half an hour after, plus weekends…

What has contributed to widening this gap?

The factors are multiple. For my part, I’m convinced that everything computer digitization has killed the system a bit. We wanted to simplify teaching, but we didn’t help develop these teaching positions either… There’s also the position itself. Full-time judo teacher? They told me when I was young to never do that, and yet I did it. You can do it, but it requires time, investment, commitment. Today, since there’s no longer this commitment and desire, it’s more complicated.

What’s the lever to change that?

Young people, they’re willing to come teach judo classes, very good, but they need the salary. Only, in small clubs like ours, eighty license holders don’t give full-time to a judo teacher. You have to find a job on the side. And in our sector, there are no jobs. Society, in Ain, may take care of big clubs, but alongside that the job market remains weak. We’re not in the Paris region where there are more easily opportunities, and so if you already have either the diplomas or the skills, you can already get by, supposedly. And then, the salaries of a judo teacher in Paris, they’re not those we have in the provinces.

Do you think that’s one of the explanations for the gap that’s widening between Paris and the provinces in recent years?

Salary-wise, no club can offer full-time today. Hence the story of the big Ain club – he pooled resources to be able to make a big employer position and it’s an interesting economic model. That’s why clubs now make alliances to be able to precisely have the instructor that fits. That way, they can share him and the instructor manages to have a decent salary.

You developed a late taste for experiences abroad. What could motivate guys of twenty-three or twenty-five who hesitate to get started?

I think people do it more and more, imagine that. Social networks have a lot to do with it, by the way. It’s hard to turn off your phone, even on vacation… At night in your bed, you turn on your phone or tablet and you see the networks. You see some becoming judges, I see young people who were at training camps in Valencia, Zagreb, Jičín, others who were at tournaments. In short, if you follow a little, you get informed. And if you get informed, you tell yourself why not me – or why not us, because it’s still nice to travel with your club mates. You inquire, you send emails, and then it ends up working out… And then I also think people are starting to get out a bit because once again, the offers in France are much fewer than before.

Meaning?

With all the costs, all the regulations, how do you want to compete? While you go to Italy for two hundred euros a week, you go to Croatia it’ll cost you two hundred fifty euros a week – not the trip, but the week of organization. In France, you have nothing for less than three hundred fifty euros. When I see my brother-in-law who lives near Narbonne, a beer at six euros while I paid two euros for it! You go out once with friends but you don’t go back. There’s a problem.

Training in Poland in 2019. © Judo King Wieliczka/JudoAKD

Do you feel the passing of your sixtieth birthday, or is it just another candle?

For now, it’s fine; we’ll see how it goes from here. But I think it’s more the French government that treats you differently once you turn 60. On my birthday, I received an email that basically said, ‘Hello, you have health checks to do!’ [Laughter].

How do you see the start of the 2025 season at the club?

I’m seeing more and more children doing lots of different activities. It’s a phenomenon that I’m observing more and more, and it makes me wonder: is it good for them and their ability to concentrate? Is it what they want, or what their parents want?

An anxiety of emptiness, perhaps? Or the fear that there might be holes in the schedule?

That questions me, because I know that children also need to go through phases of boredom… Is it a way for parents to entrust their child to someone trustworthy while they work? We’re a bit of a leisure center, a bit of a daycare sometimes, for some. Because competition, it doesn’t really interest many people anymore. It’s decreasing at breakneck speed. It’s funny actually when you see mid-June arrive, that moment when competitors are starting to ease up because they’ve had a full season. On the side, you have those who announced they would stop at the end of the season – they paid so they’ll hold on until the end. You’d like to work calmly with the competitors to prepare the next season. The profiles and expectations are never uniform. That’s also what makes the charm of the profession.

A profession that must also deal with numerous refereeing adjustments…

On refereeing, I often think back to this phrase from Alain L’Herbette, who was an excellent competitor and remains a very good instructor and a very good referee. One day he made a remark: « our generation didn’t know how to transmit. » It’s true that at the time, all instructors were referees. That era wasn’t transmitted, we became professional instructors. The evolution of this profession happened very quickly. We forgot refereeing, so there’s no longer any succession in refereeing schools. It’s coming back, but it’s not the same anymore. For teaching, it’s a bit the same: we mustn’t lose sight of passion.

Summer has been unusually quiet on the senior international circuit. Do you think that it will have repercussions on license registrations?

Already in 2024 we didn’t have the usual post-Olympics explosion. In itself that’s understandable since Paris 2024 was the showcase for all sports. Since we were at home, we talked about all our French athletes: cycling, fencing, paralympics, swimming, handball, team sports… The offer being multiple, people registered in all sports. Basically, all disciplines increased, but in small doses rather than one big discipline like ours as sometimes happens. Look at the providers: when you watch television, we only talk about those who can have medals. You had cycling at one time, swimming, fencing, and then judo. The others, we hardly talked about them. We said that in equestrian we had a gold medal, but it stopped there. Today, equestrian, we saw it at the Palace of Versailles, it was beautiful. So we talked about it, so people took up equestrian, whereas before we didn’t talk about it.

If today’s Pierre could give advice to the Pierre who was putting on his white belt for the first time when he was nine-ten years old, what would he tell him?

That’s a tough question, that’s a tough answer. I can’t hide from you that the heart of everything remains passion, and for me it fell on me like that, almost by chance. Is it the supervision I received that sparked that? Is it the group of friends we had at the start? That club atmosphere – which no longer exists either; try fooling around in the locker rooms or showers today, you’ll end up between the four columns of the courthouse… Come on, what I could tell him, that Pierre who will take his white belt: it’s to be dedicated and attentive, first, and to have fun.

Would you for example have started traveling earlier or things happened this way and it’s very good like that?

I would have liked to, yes… Once again, what played a role was family life because I had my children, I didn’t travel before. I stayed in France, I had never pushed the door except Switzerland, Italy or Spain, nearby countries, you know. I went to England thanks to school trips of the time – which today no longer exist, there too. We’ve lost quite a few of these things… And at the same time I also tell myself that, thanks to judo, I’ve practiced almost everything. I did parachuting, horseback riding, motorcycling, things like that. It’s not always my cup of tea in the end, but at least I tried. I tried archery, golf, water skiing. And all that is thanks to judo.

And in the end, it’s judo you prefer, right?

In any case it’s judo that allowed me that. I hope other sports can do it too. And that, I don’t know, because the problem is I’ve only known that. If I’ve known other things it’s because I opened myself to that and I met the right people. I wouldn’t have been in this environment, I’d be at the factory. I might not have known someone who has a boat and who offers me to water ski.

And then there are all these nationalities crossed along the way…

Yes, I maybe felt more freedom when I created my club. When they told me « We’re organizing a tournament, » I said OK but I don’t want to do like the others because making a draw, putting four mats, with three referees on the mat, it’s easy with experience, but I get bored quickly. And that’s where I got into international: « Come on let’s go. We have to do it, we have to discover, we have to try. » I once did a Franco-German exchange with the twin city with the Croix-Rousse neighborhood. We did the same with Bourg-en-Bresse, I have good memories but it remained vague, I couldn’t develop that. On the other hand when I did exchanges with international thanks to my tournament, it made me want even more. It freed something.

The advice you would give to young instructors today?

Don’t wait. Japan, I went there late and it’s thanks to Patrice Palhec, and behind that I took teams. Young people, when I offer them, they tell me « Wow, it’s going to cost us a lot. » I tell them: « Do it now, after it’s too late, I did it too late. » I took advantage of it as a leader but I would have liked to have the opportunity to do it as an athlete. – Interview by Anthony Diao, spring-summer 2025. Opening picture: ©Akiyama Settimo Archives/JudoAKD.

A French version of this interview can be read here.

More articles in English:

-

- JudoAKD#001 – Loïc Pietri – Pardon His French

- JudoAKD#002 – Emmanuelle Payet – This Island Within Herself

- JudoAKD#003 – Laure-Cathy Valente – Lyon, Third Generation

- JudoAKD#004 – Back to Celje

- JudoAKD#005 – Kevin Cao – Where Silences Have the Floor

- JudoAKD#006 – Frédéric Lecanu – Voice on Way

- JudoAKD#008 – Annett Böhm – Life is Lives

- JudoAKD#009 – Abderahmane Diao – Infinity of Destinies

- JudoAKD#010 – Paco Lozano – Eye of the Fighters

- JudoAKD#011 – Hans Van Essen – Mister JudoInside

- JudoAKD#021 – Benjamin Axus – Still Standing

- JudoAKD#022 – Romain Valadier-Picard – The Fire Next Time

- JudoAKD#023 – Andreea Chitu – She Remembers

- JudoAKD#024 – Malin Wilson – Come. See. Conquer.

- JudoAKD#025 – Antoine Valois-Fortier – The Constant Gardener

- JudoAKD#026 – Amandine Buchard – Status and Liberty

- JudoAKD#027 – Norbert Littkopf (1944-2024), by Annett Boehm

- JudoAKD#028 – Raffaele Toniolo – Bardonecchia, with Family

- JudoAKD#029 – Riner, Krpalek, Tasoev – More than Three Men

- JudoAKD#030 – Christa Deguchi and Kyle Reyes – A Thin Red and White Line

- JudoAKD#031 – Jimmy Pedro – United State of Mind

- JudoAKD#032 – Christophe Massina – Twenty Years Later

- JudoAKD#033 – Teddy Riner/Valentin Houinato – Two Dojos, Two Moods

- JudoAKD#034 – Anne-Fatoumata M’Baïro – Of Time and a Lifetime

- JudoAKD#035 – Nigel Donohue – « Your Time is Your Greatest Asset »

- JudoAKD#036 – Ahcène Goudjil – In the Beginning was Teaching

- JudoAKD#037 – Toma Nikiforov – The Kalashnikiforov Years

- JudoAKD#038 – Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard – The Rank of Big Sister

- JudoAKD#039 – Vitalie Gligor – « The Road Takes the One Who Walks »

- JudoAKD#040 – Joan-Benjamin Gaba and Inal Tasoev – Mindset Matters

- JudoAKD#042 – Theódoros Tselídis – Between Greater Caucasus and Aegean Sea

- JudoAKD#043 – Kim Polling – This Girl Was on Fire

- JudoAKD#044 – Kevin Cao (II) – In the Footsteps of Adrien Thevenet

- JudoAKD#045 – Nigel Donohue (II) – About the Hajime-Matte Model

- JudoAKD#046 – A History of Violence(s)

- JudoAKD#047 – Jigoro Kano Couldn’t Have Said It Better

- JudoAKD#048 – Lee Chang-soo/Chang Su Li (1967-2026), by Oon Yeoh

Also in English:

- JudoAKDReplay#001 – Pawel Nastula – The Leftover (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#002 – Gévrise Emane – Turn Lead into Bronze (2020)

- JudoAKDReplay#003 – Lukas Krpalek – The Best Years of a Life (2019)

- JudoAKDReplay#004 – How Did Ezio Become Gamba? (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#005 – What’s up… Dimitri Dragin? (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#006 – Travis Stevens – « People forget about medals, only fighters remain » (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#007 – Sit and Talk with Tina Trstenjak and Clarisse Agbégnénou (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#008 – A Summer with Marti Malloy (2014)

- JudoAKDReplay#009 – Hasta Luego María Celia Laborde (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#010 – What’s Up… Dex Elmont? (2017)

And also :

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#01 – Episode 1/13 – Summer 2025

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#02 – Episode 2/13 – Autumn 2025

JudoAKD – Instagram – X (Twitter).