Born on February 17, 1974 in Chisinau (USSR until 1991, Moldova since), Vitalie Gligor is one of those precious encounters that judo word-of-mouth makes possible. It goes back to autumn 2023, on the occasion of an extraordinary exchange with the all-too-rare Andrzej Sadej from Judo Canada. The initial topic concerned the sustanable development of judokas. One thing leading to another, the conversation had turned to another area of expertise of the former Polish international: Paralympic judo. In this field, the terms integrity, altruism and consistency are almost obligatory passages. Now, on these grounds, the name of Vitalie Gligor quickly appears essential. This is what our first discussions a few weeks later would confirm.

Gaunt face, sharp words, the man never gave up on his childhood friend Oleg Cretul (Kretsul during the years they spent together in Russia), despite the tragic car accident that led the Moldovan U78kg holder at the Atlanta Olympics and runner-up to Frenchman Djamel Bouras in the final of the 1996 European Championships to lose, nine days after his marriage, his wife, his brother-in-law and, despite thirty days of intensive care, his sight.

Ten months and many conversations later, an investigation appeared in the French daily Libération, devoted to the patient path of righteousness of people such as the Moldovan coach facing « fake visually impaired » and « real cheaters ». On the last evening of the Paris Paralympic Games, a handshake at the foot of the stands and a promise: that of taking the time to introduce to as many people as possible a rare trajectory and perspective, marked by a long sequence in Russia and a path made of convictions and, necessarily, adaptation. Nearly a year has passed since this commitment. Here we are. – JudoAKD#039.

A French version of this interview is available here.

We are at the end of September 2024 when this interview begins, as we had agreed near the Arena Champ de Mars on the evening of the last day of the Paralympic Games. How are you, three weeks after the end of this event?

After the Paralympics, we still had ten to fifteen days of media attention and official meetings. The tension during the preparation for the Paralympics and then the event itself cannot be compared to any other competition. You come out of it psychologically exhausted because you realize that four years of work have just been played out. The fatigue manifests itself as apathy towards everything – work, sport, and even your loved ones.

Are you proud of your athletes?

I am satisfied with the result, although I realize that we deserved better. I am particularly proud of Oleg Cretul’s performance… I would like to emphasize his will, which belongs only to true champions. His draw was terrible: in addition to Oleg, who is a multiple World, European and Paralympic champion, there were on the road to the final the Frenchman Cyril Jonard (2022 World champion and 2004 Paralympic champion), the Iranian Mousa Gholamishafia, 2023 World champion, and the Briton Daniel Powell, silver medalist at the 2022 World Championships and 2023 European Championships. Faced with such opposition, each encounter was a final before the final. Right from the start, Oleg had to face Cyril Jonard, who has always shown incredible strength and good physical preparation.

And who was competing in front of his home crowd!

Indeed: add to that this incredible support from the stands, but also the fact that Oleg had shown signs of a viral illness the day before his first match and that his condition was not very good. The fight lasted almost eight minutes. It exhausted him so much that after leaving the mat, I was sure that Oleg could not continue the competition because of his health condition, as he was almost losing consciousness… But he didn’t want to give up. Despite my pleas. Because I was literally afraid for his life.

To that extent? Yet he continued and even made it onto the podium…

Yes, he managed to defeat an Iraqi then the Iranian World champion and, by sheer force of will, an athlete from Turkey whom he threw for ippon. This bronze medal was probably the most difficult trophy of his career… I am proud of Oleg’s character and his brilliant technique.

Another of your athletes finished with a medal on September 7…

Yes, Ion Basok. To be objective, he had more ease qualifying for the Games final. I expected more from him in the final fight but this remains the most beautiful result for Moldova at the Paralympic level, across all sports. After that, in life, I always sincerely thank God for everything he gives. He alone knows how much we deserve!

What did you learn as a coach and as a man during this last Paralympic cycle?

This cycle confirmed very important things that I had intuited for a while, but never so deeply. To succeed, it is necessary to create a positive, friendly and trusting atmosphere in the team, while maintaining iron discipline. It is also necessary to seek an individual approach for each athlete. Understanding what motivates them and how to strengthen this motivation, if necessary by example, for maximum commitment on their part.

After Paris, the athletes are healing their wounds… Some need to undergo surgery, others need long rehabilitation and recovery. Until 2025, the Paris medalists will have an individual training program and will only come to the gym if they wish. It is very important to give them complete rest, close to their family, with recovery sessions, so that they are strong and eager to restart the four-year marathon whose finish line this time will be in Los Angeles. During this period, the focus should be on athletes who did not participate in the Paris Games.

And you, how are you experiencing this period?

I too, as a human being, need rest, with the possibility of analyzing all the errors in my training. Ideally, I would like to dedicate this recovery period to my family while making plans for the future. I have always had ideas of working in another country, where the necessary conditions for developing para-judo are created.

Is it more complicated in Moldova?

In the Republic of Moldova, where para-judo did not exist until 2018, we had to build from scratch a system that allows this development, from the creation of the Disabled Judo Federation and the direction of the Paralympic Committee to changing legislation at the government level. We must recognize that the situation in the country is evolving every day for the better and this is due to the success of our athletes as well as close cooperation with the government. The country’s leaders are interested in developing the Paralympic movement in Moldova. I will make a decision later, after analyzing all the circumstances. The essential thing, in the current regional context, is that there is peace.

These are not your first Paralympic Games. What were the main differences between Paris 2024 and the previous ones?

These are my fifth Paralympic Games indeed and there are many comparisons to make. For me, the difference is mainly that, at these Games as at those in Tokyo in 2021, I came not only as a coach, but also as first vice-president of the Paralympic Committee of Moldova. That is to say, I was both one of the leaders of the national team and also one of the people involved in organizing our joint team’s participation in Paris. Organizing an event of such magnitude requires the coordinated work of a large number of people. Naturally there are gaps, but they could hardly affect the festive feeling in Paris. And what was particularly memorable was the incredible support from the packed stands! I have never seen such support from spectators before! You can feel that the French know judo and that judo is very popular in France!

In France precisely, the entire community was devastated by the announcement in autumn of the sudden disappearance of French coach Cyril Pagès, who was also very involved with Paralympic athletes – and who had responded to me at length a few months earlier as part of the investigation for Libération. Did you know each other well?

Absolutely… For me, Cyril will always remain that smiling, well-mannered, positive and always sincere person. I don’t remember the first time we met. I just know that he was my link with the French national team. He spoke a little English, I often talked with him and I felt that we had a lot in common… He was often on the chair of my athletes’ opponents. When he bowed at the end of a match, he shook my hand sincerely and very respectfully, regardless of the outcome of the fight. I also saw him in randori with Hélios Latchoumanaya during training camps. You could feel that he was a high-level athlete, which added to the respect he inspired as a judoka… His smile and his open heart are impossible to forget… Cyril was on Cyril Jonard’s chair in Paris, during the fight between Jonard and Oleg Cretul. The last time I saw him was at the Paralympic village that evening, when he went to dinner with Jonard after the competition. I sincerely congratulated them both for their bronze medal. Cyril was translating to Jonard by showing on his fingers the sign language for the deaf-blind. I don’t even know who can communicate with the deaf-blind apart from him on the team – I remain admiring of his ability to work with athletes of this profile… I will sincerely miss him. I can’t believe that I will no longer see that smiling face and that light-hearted person in the French team…

At the Paralympics, coaches are much more than simple coaches. Can you tell us more about the relationship you have with your own athletes?

Working with para-judokas, particularly with those who are totally blind, I realized that you no longer belong to yourself… You cannot plan your day during training camps and competitions without coordinating and providing your athlete with everything that is necessary. Imagine a day with a blind athlete and you will realize that you are an accompanist in the good sense of the term.

What is a typical day like, in this configuration?

Waking up and going to have breakfast alone while drinking a cup of coffee is not a solution. In the morning, in addition to your tasks, you must: help if necessary to find what is needed; then go to breakfast (and before that, go to the weigh-in, if necessary); first go see what’s at the buffet, get what the athlete wants (with its frequent corollary: standing in a long line for a dish); then go get drinks; then go get coffee or tea; then find napkins or utensils (spoon, fork); then the athlete asks again for a dish he/she particularly liked; when you start choosing breakfast foods, the athlete may ask for more fruit; when you finally sit down to eat, the athlete asks for dessert, because the coffee is getting cold; then he asks for more coffee; and when you sit down to eat, he/she asks if I’m going to eat soon, because he/she has been eating for a long time and wants to go to the bathroom [laughs]! The same goes for lunch and dinner… And I’ll let you imagine if you have not one but two to three totally blind people.

In fact everyone needs constant attention: to take a walk, to wash the kimono, to prepare sports nutrition, to go to the store (if you have time), just to discuss something, and so on [smile]… During flights, you also have to accompany the athletes, load and unload their bags, take them to the bathroom, take them shopping and try to explain to them what’s on the shelves, what color it is and if it suits them (if it’s clothes or glasses for example, or what else might interest them). In short, you need strong nerves [laughs]! They are often very vulnerable, with their own psychological particularities and traumas.

Of course, there are quarrels and breakups, because the coach has his own desires and problems too… But over time, you adapt, while realizing that you are giving the athlete what is most precious: your time. Basically you can only rest when you return after the competition, when the athletes go home – moreover, it is often necessary to accompany them home [smile].

You are known for your commitment to competitions without cheating, which has earned you some enmities. Where does this cause stand, after Paris?

I am indeed an ardent opponent of manipulation in sport and a supporter of fair competition. It is no secret that, in Paralympic sport, it is not uncommon for medical documents to be falsified in order to pass the medical classification stage. I have spoken about this openly and more than once, including from the podium of the General Assembly of the International Paralympic Committee. I believe that this body, as organizer of the Paralympic Games, is obliged to prevent the participation of athletes who do not meet the criteria of international medical classification. For me, sport must correspond to a fair fight. And it must always remain outside political issues.

I read on the European Judo Union website that you started judo at the age of nine and suffered a serious injury at the age of nineteen. What did you understand about judo during those early years?

My initiation to judo indeed began at the age of nine. It was in 1983, in the Soviet Union, where sambo, freestyle wrestling and classical wrestling (today Greco-Roman) were popular. On the other hand, I didn’t know much about judo. At that time, karate was banned in the Soviet Union and, for me as for many children, judo in a white kimono was something exotic, similar precisely to that karate which seemed so attractive in films… I came three times to the gym hoping to sign up for judo, but the coaches refused, informing me that they only accepted children of ten years old and that I should come back in a year!

That’s funny because a champion like Pawel Nastula from Poland was also told the same thing at the same age!

It was a real blow. I went home in tears. But the third time, I managed to convince the coach that I didn’t want to wait a year and that I wanted to start training now! Apparently, I was very emotional and he let me enter the gym, telling me not to tell anyone [smile]. I started to progress quite quickly and, in the first competition, I won first place, which gave me confidence. Since then, I became addicted like a drug addict to these winner’s emotions!

How did it continue for you, then?

After three years of practice, I entered the Republican Sports Boarding School, where the best athletes from the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic, one of the fifteen republics of the USSR, were admitted. This was one of the most difficult physical and psychological loads of my sporting career, because two training sessions per day (where ten kilometers of jogging were often just a warm-up) + morning exercises at 6:30 AM + six lessons per week, did not give the possibility to recover. The tired bodies of children experienced many failures. There were often injuries, which slowed down the child’s development, whose competition performance was thereby diminished. It was only a few months later, after leaving the sports boarding school, that I again felt the desire to train and began to progress. During all this period, we hardly understood what judo was. We only perceived it as a kind of wrestling, without understanding all the philosophy of this Japanese art. It was only many years later, when I became a coach, that I began to discover this type of martial art and see it with different eyes.

And then you had this serious injury…

Indeed. I was nineteen years old in 1993. This is the period when the Soviet Union collapsed and independent Moldova, like all the republics of the Soviet Union, was going through a very difficult period: unemployment, rampant crime, corruption in all power structures and often famine. It was during this period that I seriously injured my knee during a training session. I had to undergo surgery but, at the time, it was difficult to organize and there was no money to finance it. So I stayed at home for two weeks then, little by little, limping, I started coming to the gym, but only to do physical training. It was only a year later that I returned to the tatami. My knee has always bothered me since – and it still bothers me today.

You still kept a foot in the high level…

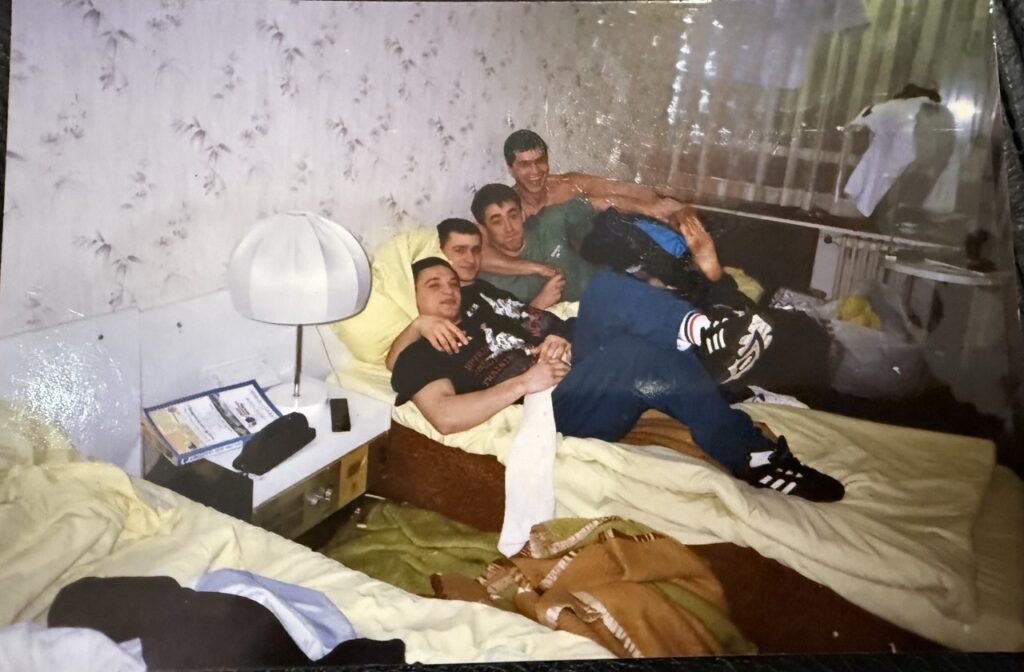

At the age of twenty-two, I was coming regularly to train. I was Oleg Cretul’s partner when he was preparing for the Atlanta Olympics. In 1996, I managed to participate in international category A tournaments in Prague and Warsaw. Unfortunately I was not competing in my weight category of U71kg, but in U78kg. And I didn’t have much success.

What was your state of mind at the time?

Judo was my passion, but I was training without a personal coach and I was learning based on what I saw from others. Today, I realize that this fact partly prevented me, like many other athletes, from fully realizing and understanding the deep meaning of judo.

You also say that Oleg Cretul’s car accident was a turning point for you. What would your life have been without this tipping point?

Let’s put this in context. After the Atlanta Olympics, Oleg and I try to launch ourselves into the new realities of the country’s wild market economy. Deception and fraud are commonplace. Businessmen are often in cahoots with criminal gangs. We ourselves come into conflict more than once with various criminal gangs, simply to defend the interests of our nascent business. It’s a very difficult time. The laws don’t really work. Crime and corruption are the norm… I have often discussed with Oleg what would have happened if he hadn’t had this accident. Given that Oleg has always been undiplomatic and very bold, we both admit that it is quite likely that we would not have survived until today. Basically, either we would have been victims of a criminal gang, or we would have had to emigrate abroad, like so many of our fellow citizens, to seek a better life. Working in Russia turned out to be an opportunity to survive these difficult times for Moldova.

What did you know about Paralympic sport before taking care of your friend?

In 1997, almost six months before the accident, Oleg brings back T-shirts from the European Youth Championships in Odivelas. These T-shirts feature a photo of two judokas with a belt over their eyes (which is not very striking), and at the bottom there is an inscription: Judo European Championships, defectos visuales. We then realize that this is a competition for visually impaired people. We laugh about it at the time, not understanding how visually impaired people could fight. Especially since in distributing these T-shirts, they don’t explain to those they give them to that these are really T-shirts from blind judokas’ competitions. And then six months later, Oleg has his accident and loses his sight.

And you think back to those T-shirts…

Not even. We only remember those T-shirts three years later, when we receive an invitation from the Olympic Committee of Moldova – there is no Paralympic Committee in Moldova at the time – with the program of the 2000 Paralympic Games in Sydney where, among other disciplines, there is judo for visually impaired people. This news is the starting point of our Paralympic life and career. We don’t go to Sydney nevertheless because Oleg didn’t participate in the qualifying competitions, even though we obtained accreditation for me as a coach. Having started working with Paralympic athletes, I radically change my attitude on many points.

Which ones?

First, I don’t perceive them as people with disabilities, but as athletes. I react very strongly if I feel discrimination against them. They, in return, teach me to enjoy life whatever the circumstances. Often too, in difficult situations, they are a source of motivation and psychological support for me. I don’t like it when people openly show pity towards them and try to give them « a fish instead of a fishing rod. »

You also have extensive experience in Russia. How does it go for you on the Paralympic side during those years? Is it very different from what you knew then in Moldova?

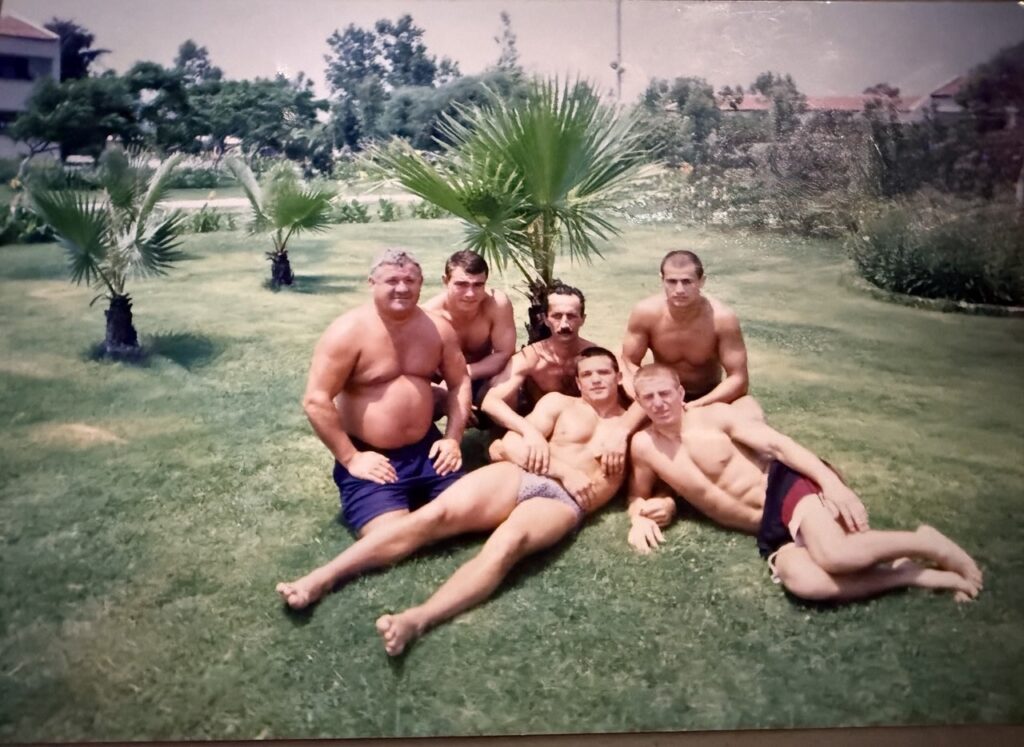

I work with the Russian Paralympic national team from 2001 to 2018. From 2004, I practically manage the training process of the Russian national team and, at the end of 2011, I become the head coach of the Russian men’s national team. It’s a unique opportunity to acquire invaluable experience, which I still rely on today. Thanks to the support of Sergey Soloveychik, then president of the EJU, I begin in 2007 to have Paralympic national team leaders participate in training camps with Olympic judokas. I gain great experience organizing these training camps under the direction of head coach Sergey Tabakov in the Caucasus, in the village of Terskol, when Tagir Khaibulaev, Ivan Nifontov, Mansur Isaev and other athletes who later brought glory to Russian judo were still very young athletes. However, the real discovery for me was the training camp with the Russian Olympic team under the direction of Ezio Gamba.

Meaning?

Ezio for me is a man fanatically devoted to judo. For him, judo is the meaning of his life! I learned a lot from his training and I apply it today to training my athletes. In 2012, I participate with Oleg, then Oleg Kretsul, in the last training camp of the Russian national team before their departure for the London Olympics. I wanted to understand how Gamba completes the preparation for the Olympic Games. Many things are new and very instructive for me. I remember Ezio’s phrase when we discussed with him what he emphasizes in the final phase of training, to which he replied: « the most important thing is that the athlete is fresh and ready before departure. »

What else do you learn from contact with him?

I analyzed his training plans, but to understand his training system in depth, you have to go through the entire four-year training cycle of this genius coach. Another strong point of Ezio is that he is an excellent psychologist, capable of uniting a multinational team and becoming a close friend to them, while maintaining iron subordination and discipline. I even discussed with him the possibility of uniting the Olympic and Paralympic judo teams, and he was ready to do it, but the leaders of the Russian Federation of Sports for the Visually Impaired were jealous of this idea… Working in Russia also allowed me to understand how different structures interact: the Ministry of Sports, the Federation, the Paralympic Committee, the national team training center and other structures involved in creating conditions for optimal athlete training. Of course, Russia has a different scale and great opportunities.

In 2018, you return to Moldova…

Indeed, back in Moldova, we try to start developing para-judo, but we encounter a lack of understanding in many sports organizations.

How so?

We have to build from scratch a structure that will allow us to create a base for its development in the country. For the development of a new discipline, I need a leader who could attract the attention of state structures through his results.

Oleg Cretul?

This leader could indeed be Oleg Cretul, but he is exhausted. He is exhausted both by many years of hard work since he was the leader of the Russian national team for fifteen years, being the only male judoka who is a Paralympic champion, four-time World champion and three-time European champion. He is also terribly disappointed after the unfair suspension (Oleg never took anything prohibited!) that prevented the Russian Paralympic team from participating in the 2016 Rio Paralympic Games. So, in 2017, he decides to end his sporting career and, on the strong recommendation of a cardiologist (Oleg had been registered with a cardiologist since 2010 due to high blood pressure), he begins a long process of rehabilitation and recovery.

And yet he will resume…

Yes because I manage to convince Oleg to try to move on to another four-year cycle and perform in Tokyo as a member of Moldova’s national team. I am very grateful to him for this difficult decision, considering that Oleg is already forty-two years old at the time and had in his « baggage » a large number of surgical operations, injuries and problems related to the cardiovascular system. We also decide to appoint him to the position of president of the Moldovan Paralympic Committee, knowing that by effectively managing this organization, we could contribute to the development of Paralympic judo. Oleg therefore becomes president and I become first vice-president of the Paralympic Committee of Moldova, knowing that I need a lot of work to develop the organization, given that Oleg is blind and is also an active athlete.

How does all this materialize?

The experience of working in Russia helped us a lot. We also created the Disabled Judo Federation, although we faced certain difficulties and misunderstandings. Today, the structure created gives tangible results: at Tokyo 2020, our Moldovan Paralympic team was represented by six athletes including two judokas (Oleg Cretul and Ion Basoc, seventh). At Paris 2024 there were five athletes including three judokas. Including a woman, moreover – for the first time in Moldova’s history. And for the first time in Paralympic Games history, our athlete Ion Basoc wins a silver medal, and Oleg Cretul a bronze medal, he who had previously distinguished himself under the colors of the Russian Federation. In all of history, our Paralympic athletes have only won two bronze medals, in 1996 (table tennis) and in 2000 (athletics)… And all this although Moldova does not have a single sports base for training camps!

This seems far from being the only problem that had to be solved…

In Moldova, we faced a large number of problems, the solution of which relied on national legislation and the absence of a regulatory framework: the lack of doctors and medical support for teams; the lack of coaches, psychologists, training conditions; the lack of possibilities to get to training and many others… But we live according to the principle « the road takes the one who walks. » Today we have close cooperation with state structures, support from the presidency of the Republic of Moldova and the gaps in legislation are gradually being eliminated. Today, six para-judokas participate in World and European championships and are real candidates for participation in Los Angeles 2028.

Wise people say that it’s only at the moment of return that journeys truly begin. Is this something you felt when you returned to Moldova? What did your years in Russia change in your way of teaching judo and leading your team?

In Russia, I was only the national team coach – even though I had to solve a certain number of organizational tasks. I depended on decisions made by people distant from judo, often themselves confronted with the incomprehension of Federation officials and the Ministry of Sports. In Moldova, in addition to coaching the national team, I also manage the development process of the Federation and the Paralympic Committee. This increases the workload, certainly, but it also simplifies decision-making for important tasks – which therefore considerably reduces the number of negative emotions [smile]. In Russia, I learned to manage a large team, to try to create a united team, to create training cycles, to try different training methods best suited to visually impaired people, to interact with people from different cultures and religions. In Moldova, there are fewer athletes, which allows us to pay more attention to each of them, but there are still many problems to solve and this is the challenge we’re taking on, which makes the process more interesting. The more difficulties there are in the struggle, the more beautiful the victory will be!

What are these different problems?

Today, we are facing a number of challenges, many of which are fantastic. One of them is building a modern sports facility accessible to people with disabilities… What we have managed to achieve in Moldova can become an example for many countries that, for long years, have had only one or even no Paralympic judoka engaged in international competitions. This comforts us in the idea that everything is possible – and we’re going to try to prove it!

In 2019 in Tokyo, I had the opportunity to interview another renowned Moldovan, former -66 kg Denis Vieru – with the valuable assistance of Romanian Andreea Chitu. He explained to me that he had a sparring partner dedicated to him daily. Is this the model you apply with your athletes?

I remember the period when I went to the training camp of the Moldovan senior judo team… It was in 1990, I was only sixteen years old and Oleg Cretul was fifteen. We were the partners of the national team members and, depending on the session’s theme, we only fell. This is how the preparation system works for national team holders before important deadlines. Unfortunately, this model is difficult to implement with Paralympic athletes. In Moldova’s Olympic team, forty to fifty people train and the holders have enough partners. We have our own competition calendar and we train according to our own plan, based on our preparation stages. We thought about joint training, but we don’t have the same training stages. The session goals are different, the training level of some of our athletes doesn’t correspond to the Olympic team’s level, and the specificities of individual work with athletes don’t allow total integration into national team training. But we periodically participate in randori fights with the national team.

How?

National team members want to train to improve their results and wish to work with higher-level athletes to progress. They are not very inclined to train with Paralympic athletes, because they realize they’re not working to improve their results, but to improve the Paralympic athlete’s results, and they’re not progressing themselves.

Since 2007, thanks to the help of Sergey Soloveychik (former UEJ president), I participated in joint training camps with Olympic athletes, but only with two or three athletes – Oleg Cretul and two high-level visually impaired parajudokas, who didn’t need to be accompanied. Since then, we have participated many times in international training camps within the UEJ program – Going for gold. Unfortunately, I can’t take the whole team to these training camps, because the training level of many Paralympic athletes doesn’t correspond to that of Olympic athletes. And the latter often don’t want to fight with blind athletes.

Why?

They may face certain psychological barriers when fighting with blind athletes. They may be afraid of their colleagues’ judgment if they fight at full power, often leaving Paralympians on the mat. But it’s not uncommon, especially with Oleg Cretul, that when they fall after a successful attack by a Paralympic athlete and they try to get revenge unsuccessfully, a real uncompromising fight begins, and that’s what I need as a coach. Even though, very often, I have to persuade Olympic athletes to conduct a real fight without giving in to the Paralympian « out of pity, » because it’s very unpleasant for the Paralympian to succumb to pity. Oleg, in his best years (2004-2009), fought very dignifiedly in randoris with titled judokas such as Ivan Nifontov, Tagir Khaibulaev, Keiji Suzuki and many other high-level athletes.

What is the impact of current geopolitical tensions on Moldovan Paralympic judo? There’s the war in Ukraine of course, but also the elections in Romania and the question of your country’s adhesion to the European Union…

There’s no doubt that the war in Ukraine has a significant impact on everything happening in Moldova. We see a large number of refugees and we realize all the sorrow that war brings. Psychologically, you’re under tension, because you realize you could become a refugee too. For almost three years now, I’ve been thinking, like many people in the country, about how and where to take my family in case of threat.

Moreover, this also prevented me from concentrating on Paris preparation. Every morning, far from home, the first thing you do is read the news and pray for the war to end… This certainly has a negative impact on the Moldovan economy (which is very, very weak) and, consequently, on sports funding. Although candidate status for the European Union (as Moldova has become) requires paying particular attention to the needs of people with disabilities, and creating favorable conditions for sports practice in particular. We see the will of Moldovan authorities to solve these problems, but these problems aren’t solved only on a financial level. It’s necessary to change people’s consciousness and fight against discrimination of athletes with disabilities.

For example?

I’ll cite several cases. In 2023, when Moldovan parajudokas win the European championship title. It’s the first time in the history of the Moldovan Paralympic Committee, all sports combined. At the end of the year, during the award ceremony by Chisinau City Hall for the best athletes of the year, the European judo champion receives a bonus more than five times higher than that of the European parajudo champion! Why such discrimination? Nobody can explain it… Often honors are given to Olympians while forgetting Paralympians, as if they were second-class people… It’s sad. The Paralympic Committee after this fact – and many others – declared, at the following General Assembly, the year 2024 « Year of the fight against discrimination in sport »! And even today, we continue to speak out in the media and highlight facts of discrimination against Paralympic athletes.

We are now in June 2025. How do things look for you, at the beginning of this new Paralympic cycle?

After the Paris Games, considering our bronze and silver medals, we gave many interviews in Moldova, participated in quite a few official meetings and attended various events. Naturally, all this had an impact on the training process. After a three-year marathon including preparation but also participation in the Paralympic Games, it’s natural to allow athletes to rest physically and psychologically. This period is also an opportunity for me to determine potential candidates for the next Paralympic Games, to establish the preparation schedule for 2025, but also to reflect on the development strategy until 2028 for our Paralympic committee and the Moldovan Parajudo Federation.

And concerning your athletes?

For the athletes, the period following the Paris 2024 Games was marked by medical operations, rehabilitation and treatment of old injuries. The year 2025 began with participation in the international tournament in Germany, the Grand Prix of Georgia then the World championships in Kazakhstan in mid-May. Ion Basok (O95kg, J1) won second place in this competition. It’s a historic result for the Moldovan Paralympic Committee! From my point of view as president of the Parajudo Federation, any medal won in a major international competition is a great success. As head coach, my goal is to win the World championship gold medal and that of the Paralympic Games. All other results are only steps toward this goal.

If the Vitalie of 2025 could give life advice to the one who tied his first white belt in 1983, what would he tell him?

Difficult question… Probably never be afraid of your desires, because everything is possible in life. You just need to think and realize the sacrifices and efforts that will be needed to achieve what you want, and ask yourself if you really want it. Always formulate your goal clearly and don’t give up along the way… And above all, train your patience, if there is any [laughs]! Appreciate your friends and learn to be a loyal friend. Life itself will teach you to appreciate these things. – Interview by Anthony Diao, autumn 2024 – summer 2025. Opening picture: ©Natalia Donets/JudoAKD.

A French version of this article is available here.

More articles in English:

- JudoAKD#001 – Loïc Pietri – Pardon His French

- JudoAKD#002 – Emmanuelle Payet – This Island Within Herself

- JudoAKD#003 – Laure-Cathy Valente – Lyon, Third Generation

- JudoAKD#004 – Back to Celje

- JudoAKD#005 – Kevin Cao – Where Silences Have the Floor

- JudoAKD#006 – Frédéric Lecanu – Voice on Way

- JudoAKD#008 – Annett Böhm – Life is Lives

- JudoAKD#009 – Abderahmane Diao – Infinity of Destinies

- JudoAKD#010 – Paco Lozano – Eye of the Fighters

- JudoAKD#011 – Hans Van Essen – Mister JudoInside

- JudoAKD#021 – Benjamin Axus – Still Standing

- JudoAKD#022 – Romain Valadier-Picard – The Fire Next Time

- JudoAKD#023 – Andreea Chitu – She Remembers

- JudoAKD#024 – Malin Wilson – Come. See. Conquer.

- JudoAKD#025 – Antoine Valois-Fortier – The Constant Gardener

- JudoAKD#026 – Amandine Buchard – Status and Liberty

- JudoAKD#027 – Norbert Littkopf (1944-2024), by Annett Boehm

- JudoAKD#028 – Raffaele Toniolo – Bardonecchia, with Family

- JudoAKD#029 – Riner, Krpalek, Tasoev – More than Three Men

- JudoAKD#030 – Christa Deguchi and Kyle Reyes – A Thin Red and White Line

- JudoAKD#031 – Jimmy Pedro – United State of Mind

- JudoAKD#032 – Christophe Massina – Twenty Years Later

- JudoAKD#033 – Teddy Riner/Valentin Houinato – Two Dojos, Two Moods

- JudoAKD#034 – Anne-Fatoumata M’Baïro – Of Time and a Lifetime

- JudoAKD#035 – Nigel Donohue – « Your Time is Your Greatest Asset »

- JudoAKD#036 – Ahcène Goudjil – In the Beginning was Teaching

- JudoAKD#037 – Toma Nikiforov – The Kalashnikiforov Years

- JudoAKD#038 – Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard – The Rank of Big Sister

- JudoAKD#040 – Joan-Benjamin Gaba and Inal Tasoev – Mindset Matters

- JudoAKD#041 – Pierre Neyra – About a Corner of France and Judo as It Is Taught There

- JudoAKD#042 – Theódoros Tselídis – Between Greater Caucasus and Aegean Sea

- JudoAKD#043 – Kim Polling – This Girl Was on Fire

- JudoAKD#044 – Kevin Cao (II) – In the Footsteps of Adrien Thevenet

- JudoAKD#045 – Nigel Donohue (II) – About the Hajime-Matte Model

- JudoAKD#046 – A History of Violence(s)

- JudoAKD#047 – Jigoro Kano Couldn’t Have Said It Better

- JudoAKD#048 – Lee Chang-soo/Chang Su Li (1967-2026), by Oon Yeoh

More Replays in English:

- JudoAKDReplay#001 – Pawel Nastula – The Leftover (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#002 – Gévrise Emane – Turn Lead into Bronze (2020)

- JudoAKDReplay#003 – Lukas Krpalek – The Best Years of a Life (2019)

- JudoAKDReplay#004 – How Did Ezio Become Gamba? (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#005 – What’s up… Dimitri Dragin? (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#006 – Travis Stevens – « People forget about medals, only fighters remain » (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#007 – Sit and Talk with Tina Trstenjak and Clarisse Agbégnénou (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#008 – A Summer with Marti Malloy (2014)

- JudoAKDReplay#009 – Hasta Luego María Celia Laborde (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#010 – What’s Up… Dex Elmont? (2017)

And also :

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#01 – Episode 1/13 – Summer 2025

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#02 – Episode 2/13 – Autumn 2025

JudoAKD – Instagram – X (Twitter).