Born on 28 September 1994 in Versailles (France), Benjamin Axus has won seven individual medals at the French senior championships to date, including three titles. A European junior champion in 2014, the U73kg player from AJA Paris XX was a member of the French team at the 2017, 2018 and 2022 World Championships. Following a randori together in December 2023 at the international training camp in Bardonecchia (Italy), we agreed to follow up over the coming months. We began this interview with no ulterior motive other than to document as honestly as possible the trajectory made up of thwarted hopes of this 1.89m fighter on the road to his thirtieth year and a legitimate Olympic dream given his World ranking. It’s a trajectory that, because of what it says about a terrifying incommunicability, is reminiscent of so many others. At the top level, as the Ludwig Von 88 rockers said in one of their interludes, ‘you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs – and it’s always annoying to be the egg’. A look back at the long months that give full meaning to Kosei Inoue’s unusual public attention when, ahead of the Tokyo Olympics, the Japanese announced the names of those who would be taking part – and paid tearful tribute to all those who would not. – JudoAKD#021.

Kosei Inoue: « mes premières pensées vont aux judokas qui se sont battus tout au long de l’olympiade et qui finalement ne seront pas sélectionnés »

— ◇◆◇◆Pietri Loïc◆◇◆◇ (@PietriLoic) February 28, 2020

A French version of this interview can be read here.

As this interview begins, we are at the very beginning of January 2024, eight months away from the Paris Olympic Games. In what frame of mind are you approaching this final stretch?

It’s a very special time. I am currently the last French Grand Slam and Grand Prix medallist in the U73kg category. I’m also the first at the Olympic and international rankings. Despite this, the Federation has never given me so little consideration.

What do you mean?

In other words, I wasn’t selected for the last European Championships, nor for the training camp in Slovakia, nor for the tournament and training camp in Japan, nor for the oxygenation training camp in Les Menuires, nor for the preparatory training camp planned for January in La Réunion.

Have you had any explanations?

No, I didn’t.

How did you react?

With my club, we decided to set things up. We do a lot of training on our own and, as soon as it’s possible to go on a training camp by ourselves, we go.

For example?

Last autumn, we went to train in Valencia in Spain just before the French 1st division championships. With my friends Daikii Bouba and Maxime Merlin, the three of us went to Italy for a training camp over the festive period – where we met, in fact – and today we’re off to Mittersill in Austria for a week’s training.

What’s the state of mind, given the context?

We told ourselves that we weren’t going to expect anything from others and that we’d organise everything ourselves so that I could train in the best possible way for the Paris Grand Slam, because we realized that I wouldn’t have a lot of time left before the Olympics. My mindset today is not to think about being sidelined. I’m just thinking about training hard and sorting out all the little details so that I can get to the Paris Grand Slam in the best possible shape!

What have you improved most in recent seasons?

I’ve tried to really focus on the details of my judo. I’ve tried new things – which haven’t always worked, by the way – but, as my coach tells me, all the competitions before the Games are about fine-tuning and understanding what works and what doesn’t. We also do a lot of physical work, especially on the legs. We also work a lot physically, especially since this year. Judo today is still very physical and I have to be able to hold my own against guys heavier than me.

What do you still need to reach a milestone at this stage of the Olympics?

A bit of success I think, sometimes, and perhaps better management of strategy. These days, the rules play a huge part and I’ve often lost on strategic errors, like at the Budapest Masters in August 2023 when I got disqualified against the Kosovar even though I was dominating the fight…

I imagine it’s not easy to ignore the competitive context in your category, especially with this race to qualify for the Olympics. Have you put anything in place to stay focused on your own progress?

As I said earlier, I would have hoped that there would be healthy competition between the guys in the category, but unfortunately that’s not necessarily the case. There are preferences, clubs or coaches that are more or less appreciated by the selectors. Everything comes into play these days. What’s hard is that if the Games weren’t in France and the Federation didn’t have the host nation’s quota, they’d have no choice but to support me because I’m the one with the best chance of qualifying given the World ranking today. But that’s the way it is. I’m trying not to think about that and to focus on myself so that I can become indispensable.

When you arrive at a course like Mittersill, what’s your objective? Do you go for volume like Lukas Krpalek, who systematically doubles or even triples his randoris, or do you go for quality and precision?

I’m going to try to do a lot of fights, to really put myself in the red because we’re a month away from the Paris Grand Slam, so now’s the time to focus on quantity and, little by little, get closer to quality. The advantage of this training camp is that there’s a huge crowd, so we can have lots of fights, so we might as well make the most of it!

What’s next on your program after Mittersill?

The idea is to be meticulous. I’m going to talk about it with my coach, but we’re going to reduce the amount of training to improve the quality. There’s always room for improvement and it’ll never be perfect, but the aim is to get closer to perfection. I want to relive a tournament in Paris like I did before [third in 2022, editor’s note] and I want to do even better. I love fighting in front of the French public and today I’ve got something to prove.

You’re back from Mittersill. How did it go?

I got back on 12 January. It was a really good training camp with a lot of very high-level partners. I think it was the right time to do fights of this intensity. It’s the one that comes closest to the highest level.

What did you try to achieve there?

I set up tactical and technical schemes that worked pretty well. I tried things out, I made commitments. I was lucky enough to be able to take on the best in my category (Top 3 in the world) and that’s a very high level. Of course, during training, the best players hide their judo a bit, that’s normal. What’s certain is that no one is unbeatable and anyone can fall… All this I’ve been able to do under the watchful eye of my coach, which gives me direct feedback and enables me to draw conclusions about my attitude or the intensity I bring to a given bout.

What do you get out of it?

This must be the fifth time I’ve done this course. I think it’s the first time I’ve come out of it feeling pretty confident and like I’ve lived up to my expectations. I feel strong and fit.

What’s next?

We’re going to have to go back to the daily grind of the INSEP, but Alex has told us that we’re going to adapt the sessions more and more to start juicing up so that we’re in good shape for the Grand Slam in Paris.

You often talk about Alexandre Borderieux, your club coach at AJA Paris XX. What does he do for you on a day-to-day basis?

Having your club coach with you is very useful, even indispensable. Unlike the training courses with the Federation, I’m obviously given more and better support because my coach is there all year round and not just when I’m selected for tournaments with the French team… After that, the advantage of going with the French team is that the club won’t be able to take us to all the training camps because of a lack of funds. So it’s a good way if you’re not very attached to your club or if you come from a very small club. Today, because I haven’t been selected since September, I’m finding alternative ways of training in the best possible conditions. And I think that in these non-selections, which were initially very disappointing, I’ve found my balance with my club. Alex and I had regular check-ups during the course, so he could tell me straight away what he didn’t like and what was good. I came looking for high-intensity fights and I found them.

What was the atmosphere like off the mat this year at Mittersill?

As far as the extra-sporting stuff goes, there’s nothing better than the hot chocolate after training with friends from the club and other clubs, like my mate Guillaume Chaine who, as he too is no longer selected for the training camps, has to go off with his club to train. There’s a good atmosphere and no negative pressure. I’ve been on the tour for some years now and it’s great to see some athletes who have become friends despite the difference in cultures, like our friends from Mongolia with whom we went on a training camp and with whom I’ve kept good contact.

How are you feeling at the start of the Olympic year’s month of February?

This is a moment like no other in my career. We’re just a few months away from the Games and I’ve never felt so supported by my club while being so sidelined by the Federation. We’re a week away from Paris and, at the end of training at the INSEP, the French team staff announced their selections for the Grand Slams in Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan. And, once again, I’m not selected for either of them, despite my position as number one in the category. I asked for explanations directly, but all I got were boilerplate answers with no logic whatsoever. I know that I have no alternative but to perform in Paris. That was already a bit the case before, but now I know for sure. So I’m not thinking about that, even though it’s not easy…

One question I haven’t asked you yet: what’s your life like outside judo?

Today I have a contract with the City of Paris. I work as a community manager for all the sporting events connected with the city. It’s a contract that allows me to work just two mornings a week. This job opportunity was very important for me, not only because it gave me a foothold in the professional world, but above all because it allowed me to relax when things weren’t going well and I felt sidelined by the Federation. I was able to concentrate on other things, do other activities apart from judo and I think that’s very important for me and my balance. I feel lucky to have this contract, even if I know that it also depends on my sporting results and that, if I get injured tomorrow or don’t perform well, my ranking will drop, which would mean that I’m no longer on the ministerial lists, which would be a problem for the continuity of my contract. The same applies after the Games: we don’t know what will happen to French sport, so we hope that all the efforts that have been made for the athletes will continue. Only time will tell…

The Paris 2024 Grand Slam has come and gone. It didn’t provide much clarity in your category, as the four French entrants were eliminated prematurely. Looking back, is the Olympic challenge a boost or does it inhibit you and your direct rivals?

There’s a lot at stake, so we all want to do well because we know there will be repercussions. It’s a pressure, yes, but I wouldn’t say it has any negative effects at the moment. On the other hand, defeats are much harder to digest. They haunt us at night when we’re asleep. They haunt us in our daily lives. With family or friends, they’re there and they eat away at us. We say to ourselves ‘I should have done that’ or ‘I shouldn’t have done that’ but we have to move on, so we do everything we can to change as quickly as possible, even if it’s not always easy. That’s where the support of a coach is essential. He gets me back on track and I get back to work.

How did you get on with the post-tournament training session? Was your motivation at half mast or on the contrary, tenfold?

The course wasn’t easy because I had no visibility, I mean no competition in sight. So it wasn’t an easy camp, especially as I wasn’t at my best physically. I’d passed out during the competition and I felt I needed a rest, but it just wasn’t the right time. I had to get back to training and that was that.

At this stage in a year like this, do you feel that there is a ‘two rooms, two atmospheres’ between those who have qualified for the Olympics and those for whom the decision has not yet been made? What’s the key to staying positive? Looking beyond the Games?

There’s obviously a time lag. Once you know you’ve been selected for the Olympic Games, I think you feel more serene and you can prepare for the Games in the best possible way, while still knowing the ‘ultimate’ date when you have to be at your best. Of course there are ups and downs. There are times when you tell yourself that it’s going to be complicated, that everything is working against you… That’s when those close to me and my coach motivate me and push me to go all the way so that I have no regrets… We think about what happens afterwards, what happens if I make the Games or if I don’t make them. The stakes, the contracts, the sponsors, the personal projects, all these thoughts come together… So I tell myself that I’ll think about it afterwards and that, for the moment, I’m just going to play my cards right. I don’t want to regret anything.

Let’s take a step back and look at the Olympiad as a whole. Where do you think Olympic qualification comes into play? What were the key selections/fights for you? What would have been your ideal Olympiad if you’d had the choice of selections?

The perfect Olympiad is to win a medal at the championships. That’s the most important thing. Unfortunately, not being selected for the European Championships in Montpellier hurt me a lot psychologically. I was sidelined despite my French championship title and my Grand Prix medal, the only one for a French rider in the category this season. That’s when I said to myself: ‘If they don’t want you, they can shatter your dream without being held to account’.

What did this diagnosis change about your state of mind?

From that moment on, I understood that I wouldn’t have a choice and that I could only count on a great performance to get my ticket. If the selection came down to a hesitant choice between two or three judokas, I wouldn’t have the advantage. So I have to perform. I can’t be satisfied with my past medals. I need others.

The king of your category today is the Azerbaijani Hidayat Heydarov. Have you ever held him in your hands? You’ve already beaten his compatriot Orujov in Paris. Which of the two did you find stronger?

Yes, I’ve held him before. He’s a very strong judoka. He’s very strong physically. His kata guruma is formidable. I’m not surprised that he’s number one in the world today… Orujov’s profile is really different. He was at the top of his category for a long time. I’ve always wanted to take him on because he’s big and aggressive. I had a lot of respect for this athlete because of his record, his career and his attitude, which is always respectful of his opponents. I was lucky enough to fight him at home in Paris. It really wasn’t the best draw of my life, but these are the kind of fights that excite me – taking on an Olympic medallist and then the Japanese winner of the previous edition was really interesting and exciting. We were able to make a big golden. I had to wear him down, but I have to admit that Alexandre Borderieux had given me a very good briefing on how to handle the fight. I followed his instructions to the letter and it worked… Generally speaking, the Azerbaijanis are formidable and very aggressive opponents. It’s always an intense fight because they just love fighting!

Since this exchange, the selections for the Games have been made and you’re not in them. How did you find out?

The performance director called me a few minutes before the announcement on the networks. It was a brief discussion in which she explained to me without any real arguments. I don’t understand this choice because there was still time to decide between the athletes. Apparently the selection had to be made because there wasn’t enough time, and certain authorities were pushing the Federation to make the choice quickly.

How do you feel about this?

Unfortunately these decisions cannot be contested and we have to live with them. I would have liked to have been informed earlier about the criteria or the selection process, but that’s the way it is, it’s hard. It hurts a lot mentally. I had to inform my coach, who was completely unaware, my family, my sponsor, my friends, the City of Paris… The problem is that I find it hard to explain a choice that I don’t even understand myself.

How do you get back on track with intermediate objectives?

I left for Austria the week after, knowing that I wouldn’t be taking part in the Games. But because I went with my club, I was in a positive environment. I wanted to do what I do best: fight on the mat.

But you hurt yourself while throwing an opponent for a big ippon, didn’t you?

Unfortunately yes, after a big first fight, on a move that allowed me to win the fight I fractured a rib, which prevented me from being able to defend my chances 100% during the next fight when I lost… When the mind is hard, often the body follows.

I’m deliberately playing the federal ‘devil’s advocate’: when you say that it all comes down to the major championships, haven’t you had your chance on several occasions this Olympiad since you were a regular at the Europeans and the Worlds in 2022?

I certainly had my chances, but so did my competitors. The difference is that I always had to perform beforehand to be able to take part in these championships. I wasn’t able to take part in the last World and European championships, but my competitor was, and he didn’t get any results either.

How did the dialogue with the staff evolve over the course of the Olympiad?

There was virtually no dialogue with the staff. I really felt I’d done something wrong. We asked for a meeting in January, which they wanted to have a few days before the Grand Slam in Paris. I told them I’d rather do it afterwards. Unfortunately, they released the selection list before the meeting took place. They suggested to my coach that we do one afterwards, but what was the point? Their choice is made and I’ve already taken my case to the CNOSF for not being selected for the European championships, even though I was the only medallist on the tour, but the Federation’s influence is too great to agree with an athlete despite the best performance argument…

For those of our readers who only have a vague idea of what’s at stake, I’d like to hear you explaining how the club coach and the French national team coach work together. What do you think is the ideal way?

The club coach is the most important because when you have injuries or poor performances, he’s the only one who will always be there. National coaches can change but they also have their preferences. There are a lot of factors involved. I stayed at the INSEP for a long time, but I realized that the way I trained was changing too much according to federal choices. It was having too much of an impact on me, so I decided to train more with my club so that, even if I get injured, even if I don’t perform well, we stay focused on working and improving.

To be in action rather than in reaction…

That’s it. Sometimes when you’re at the INSEP too much, you drown in the crowd, even if the facilities and medical follow-up are top-notch. The ideal way for me to work is to take what you have to take and manage to be in harmony with both the national staff and your club coach. Unfortunately, not everything works out for the best in the best of worlds…

There’s another factor that I think is important to mention here. You had the pain of losing your mum a few years ago… I imagine that affected your commitment and your results. How did you cope?

It’s just a fact of life. I lost my mum five years ago, unfortunately, to cancer, which took her in two months. It was obviously very hard. She brought me up and I was very close to her. She came to all my competitions. I’m lucky to have an extraordinary family. Despite having separated parents and divorced grandparents, I never lacked for anything and I was always supported during that period. My club coach also helped me a lot.

In what way?

I started behaving in ways that didn’t go with my sport. I couldn’t manage my emotions well. I was even disqualified from a French team championship, which penalized my club. I was advised to go and see a shrink. Which I did, and it helped.

What memories do you have of her?

I can’t get her words out of my head because she was the one who helped me to play it down when I was losing. She used to say to me: ‘You know, it’s only sport, there are more serious things in life and when something happens tell yourself it’s the mektoub’… It’s funny for a family that isn’t religious but today I try to repeat her words to myself. It’s only sport, but I don’t want to let people decide for me, so I’ll continue to do what I do best for as long as I’m still able. And especially as long as I want to.

You’ve just come back from the Grand Slam in Dushanbe, where you lost in the second round to a Russian…

First, I was already happy to be able to go and fight in a Grand Slam with my club in a healthy environment, surrounded by people who mean well to me. Unfortunately, I made a mistake that is unforgivable at the highest level, so I didn’t perform at this competition… What I remember most about the sequence that followed the announcement of the selections is that it enabled me to highlight a lot of the problems I’ve had during this Olympic year. I had a long talk with my coach because we’re coming to the end of four years where we were focused on the Games. Today we’ve seen that goal slip away, so obviously it’s hard to stay focused and motivated.

Where do you think you stand, at this start of May?

We’ve taken the time to talk a lot. I think I need to mourn this situation that’s eating away at me. I need to be able to move forward and do it with good people around me. It’s stupid to say it, but this sport is hard enough as it is without adding all the negative people who are around and who put obstacles in your way. I’m an emotional person. I need it to move forward and that’s what keeps me going today, because I love my sport and I love the people I train with every day.

What did you do on the day of your category in April at the Europeans in Zagreb, where Joan-Benjamin Gaba, the French entry for the Olympics, climbed onto the podium? Did you follow or did you prefer to cut back?

To be honest, I didn’t follow the competition, but I was convinced that he was going to perform well. He’s in an ideal position. The Federation has been supporting him for quite some time now and he’s a very good judoka, so for me it was the competition he had to win. He did it and I’m happy for him because he has silenced the very people who selected him and who didn’t believe that a U73kg could perform internationally. When you hear selectors say that 73s are only good for teams and that it doesn’t matter what their individual results are, the aim is for them to be part of teams, well that hurts. In Zagreb he proved the opposite and I’m sincerely happy for him.

Do you have any regrets about not being in his place?

Of course I say to myself ‘I could have been there’. I try not to think about it because it doesn’t do me any good. It’s like scratching a wound that’s still healing. It hurts and it doesn’t help you heal.

Are there any plans for you to be called up for any future selections, such as those where the first-choice player from the Games won’t be?

I haven’t been called up. I haven’t been selected for either Europe or the World Team Championships. Their selection choices are clear: they don’t want me. I’m not going to get down on my knees in front of them to get selected. I’m 29 years old and I’ve still got a lot to show for my sport. Being sidelined affected me a lot at first, but now I’m not surprised by anything. They give completely random selections, they try things to the detriment of judokas who train all their lives. They favour judokas that they like personally or who were in their club before going over to the federal side. It’s always the same problems, generation after generation.

You’re far from the first to point this out. How do you deal with this situation, which seems intrinsic to top-level sport?

I try to take a step back so that it doesn’t affect me. I love my sport and my club. My coach and I are going to do everything we can to ensure that I can live my athletic career as healthily as possible, while going in search of as many medals as possible. For some it’s their ‘job’, for others it’s just sport. Today it’s my life, and I’m leading it in the way that seems most consistent with my values.

You just won two World Cups in one week, in Marrakech and then in Madrid. How do you explain this final flourish at the Olympics? Do you feel relieved of a burden?

Relieved, I don’t know. I think the fact that people are trying to push me out or show me that I no longer have a place affected me a lot. I think it’s normal for me to be in this position in these competitions. My coach and I aimed to get to my best shape for the Games, so in a way it’s normal to win. As he told me after my second final: « I’m happy for us but it’s not where I wanted us to be. » And he was right…

What’s next for you?

For the future, I’m going to go to training in July to prepare for next season and I’ll probably go abroad on my own to train in August. I still like it and I’ve shown that I’m capable of winning fights. I think I deserve to go and do Grand Prix, Grand Slams and championships. The selectors should understand that. We are here to win medals, not to settle ego wars.

If you read Loïc Pietri’s interview on this site, I imagine that there are points that echo what you are experiencing. Do you see any hope for change in the short or medium term?

Hope, I don’t know, I’m on my way. I know how the leaders can be when they have you in their sights. We have seen huge champions like Loïc Pietri get sidelined despite their exceptional careers, so I tell myself that the ways of doing things will not change immediately. We are trying to make ourselves heard by talking about mental health and impartiality in the choice of selections, but we must not forget that we are an amateur sport and as long as no one is held accountable, nothing will change. So we try to be the best we can because the reality is that if you win they will end up coming back to you. Nobody tries to oppose Clarisse or Teddy so we have to follow their example.

How is the atmosphere internally, a few weeks before the Games, given your position?

The closer the Games get, the more people are stressed and have harmful behaviors. We see meanness, physical and moral harassment. Really. I hope that tongues will loosen one day because if we were in a company some people would find themselves in very delicate positions. So I stay in my corner and I don’t make waves. Recently I learned through rumors that I was fired from INSEP. No explanation of course but it doesn’t matter. I know my values and I will continue to train to bring back medals to my Federation and my country as long as my body and my mind allow me to do it.

You carried the Olympic flame in July. How did it all work out for you to be part of it?

I had the immense honour of carrying the flame and being the last torchbearer before the Opening ceremony. We were a small group of people who were drawn at random, but also public figures. The person who gave me the flame was someone who had been drawn at random. He was very happy – everyone was! – there was a lot of enthusiasm. It was truly magical. When I finished my journey with the flame, I gave it to the flame keeper who was going to take it a few hours later to the Opening ceremony of the Games… It was a great moment, really. When I received the phone call two days before, they explained to me that there was a torchbearer missing and that, given my story and that of not being selected, they thought it was a good thing that I could still carry it. You don’t turn down such an honour, so I went with a really light heart.

Did you go to watch the judo event at the Olympics or was it too painful and you preferred to stay away?

I didn’t want to go at first, but then I was too curious and went to watch the U66kg and U52kg events. It was completely crazy, even better than the Paris Grand Slam. It broke my heart but I found it magnificent… And I must admit that it really excited me [Laughs].

How did you experience the U73kg event? Were you surprised by the final ranking?

Of course. It hurts to watch what I couldn’t have, but it’s the sport I love and it’s the magic of the Games at home!

The advent of Joan-Benjamin Gaba, the French holder in your category, individual silver medalist and Olympic team champion by scoring a decisive point in the final against the Japanese Hifumi Abe: are you happy for him or is it still difficult for the moment?

In truth, all the elements were there. He was very, very strong, really. I can only congratulate him for his performance. He must have experienced something magical!

The guy is 23, you are almost 30. Do you think it’s over for a while or, on the contrary, does it motivate you?

Obviously I tell myself that without a medal he was already very appreciated, so now I can’t even imagine… After that, once again, everyone writes his own story. I’m not going to stop myself from winning competitions. I said it and I’ll say it again: I’ll take everything I have to take.

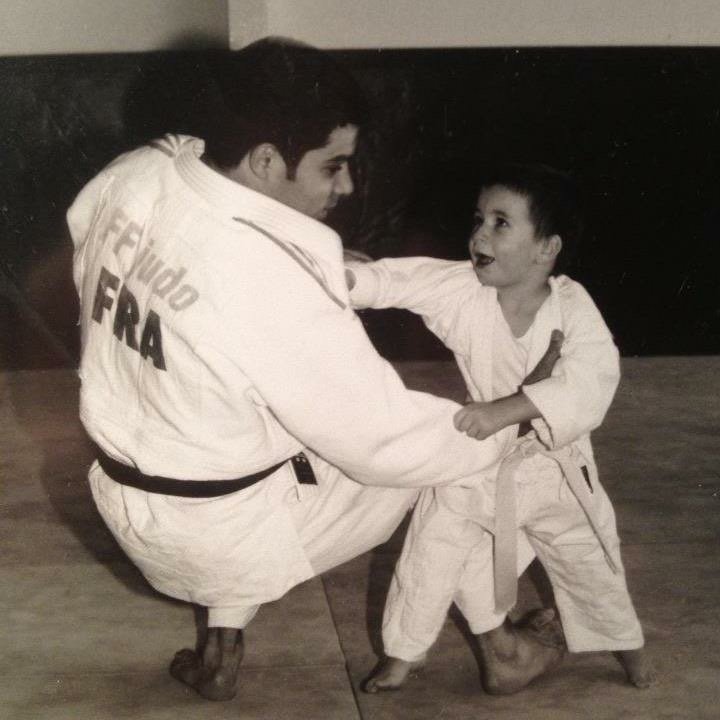

If the Benjamin of 2024 could give life and career advice to the Benjamin who tied his first white belt at the age of three, what would he tell him?

I would tell him to prepare himself mentally. We think that it’s the physical that is the hardest but for me it’s the mental that is most prone to injury and it’s the one that is the hardest to treat. I would tell him to surround himself with the right people and to not make mistakes on this point… I was three years old when I tied my first white belt. I never thought I would make a career out of it! I know that I am already very lucky to be able to make a living from my passion, even if, I admit, I didn’t think it would give me as much pleasure as pain. – Interview by Anthony Diao, winter-spring-summer 2024. Opening photo ©Laëtitia Cabanne/JudoAKD.

A French version of this interview can be read here.

More articles in English:

-

- JudoAKD#001 – Loïc Pietri – Pardon His French

- JudoAKD#002 – Emmanuelle Payet – This Island Within Herself

- JudoAKD#003 – Laure-Cathy Valente – Lyon, Third Generation

- JudoAKD#004 – Back to Celje

- JudoAKD#005 – Kevin Cao – Where Silences Have the Floor

- JudoAKD#006 – Frédéric Lecanu – Voice on Way

- JudoAKD#008 – Annett Böhm – Life is Lives

- JudoAKD#009 – Abderahmane Diao – Infinity of Destinies

- JudoAKD#010 – Paco Lozano – Eye of the Fighters

- JudoAKD#011 – Hans Van Essen – Mister JudoInside

- JudoAKD#022 – Romain Valadier-Picard – The Fire Next Time

- JudoAKD#023 – Andreea Chitu – She Remembers

- JudoAKD#024 – Malin Wilson – Come. See. Conquer.

- JudoAKD#025 – Antoine Valois-Fortier – The Constant Gardener

- JudoAKD#026 – Amandine Buchard – Status and Liberty

- JudoAKD#027 – Norbert Littkopf (1944-2024), by Annett Boehm

- JudoAKD#028 – Raffaele Toniolo – Bardonecchia, with Family

- JudoAKD#029 – Riner, Krpalek, Tasoev – More than Three Men

- JudoAKD#030 – Christa Deguchi and Kyle Reyes – A Thin Red and White Line

- JudoAKD#031 – Jimmy Pedro – United State of Mind

- JudoAKD#032 – Christophe Massina – Twenty Years Later

- JudoAKD#033 – Teddy Riner/Valentin Houinato – Two Dojos, Two Moods

- JudoAKD#034 – Anne-Fatoumata M’Baïro – Of Time and a Lifetime

- JudoAKD#035 – Nigel Donohue – « Your Time is Your Greatest Asset »

- JudoAKD#036 – Ahcène Goudjil – In the Beginning was Teaching

- JudoAKD#037 – Toma Nikiforov – The Kalashnikiforov Years

- JudoAKD#038 – Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard – The Rank of Big Sister

- JudoAKD#039 – Vitalie Gligor – « The Road Takes the One Who Walks »

- JudoAKD#040 – Joan-Benjamin Gaba and Inal Tasoev – Mindset Matters

- JudoAKD#041 – Pierre Neyra – About a Corner of France and Judo as It Is Taught There

- JudoAKD#042 – Theódoros Tselídis – Between Greater Caucasus and Aegean Sea

- JudoAKD#043 – Kim Polling – This Girl Was on Fire

- JudoAKD#044 – Kevin Cao (II) – In the Footsteps of Adrien Thevenet

- JudoAKD#045 – Nigel Donohue (II) – About the Hajime-Matte Model

- JudoAKD#046 – A History of Violence(s)

- JudoAKD#047 – Jigoro Kano Couldn’t Have Said It Better

Also in English:

- JudoAKDReplay#001 – Pawel Nastula – The Leftover (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#002 – Gévrise Emane – Turn Lead into Bronze (2020)

- JudoAKDReplay#003 – Lukas Krpalek – The Best Years of a Life (2019)

- JudoAKDReplay#004 – How Did Ezio Become Gamba? (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#005 – What’s up… Dimitri Dragin? (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#006 – Travis Stevens – « People forget about medals, only fighters remain » (2016)

- JudoAKDReplay#007 – Sit and Talk with Tina Trstenjak and Clarisse Agbégnénou (2017)

- JudoAKDReplay#008 – A Summer with Marti Malloy (2014)

- JudoAKDReplay#009 – Hasta Luego María Celia Laborde (2015)

- JudoAKDReplay#010 – What’s Up… Dex Elmont? (2017)

And also :

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#01 – Episode 1/13 – Summer 2025

- JudoAKDRoadToLA2028#02 – Episode 2/13 – Autumn 2025

JudoAKD – Instagram – X (Twitter).